Did you know that a failed German plot to distract America led to their entry into the First World War?

Following the outbreak of the First World War, the United States of America worked hard to maintain its neutrality. However, the culmination of several events in 1917 brought them into the conflict.

When war engulfed Europe in 1914, both sides looked for possible ways to gain an advantage over their opponents. Many saw the latent power of the United States of America and hoped to bring them into the conflict in support of their aims. If this could not be achieved then the next best possible solution was to ensure that America remained neutral and did not aid the opposition.

Set against these European desires was the ongoing policy of the United States to remain detached from events across the Atlantic Ocean.

Isolationism

Whilst European Powers such as Britain and France had been crucially involved in the birth of the United States during the Wars of Revolution, the country had grown increasingly detached from events in Europe. By the 19th century, America had embraced a policy of isolationism. Most of America’s outwards attention was directed towards the activities of Japan to the west, rather than Europe to the east.

This policy was not without issue. Many of those who had come to live in America had roots back in Europe, particularly in countries such as Britain, Ireland, Germany, Poland, and Italy. Thoughts within these groups regarding interactions with Europe were often split between two positions. There were those who still felt a connection to their country of origin and ancestors, and others who had purposefully left Europe behind to avoid further entanglements with European politics.

Maintaining this isolationism was much easier when there was little happening in Europe that could directly impact the activities and interests of the United States. In the immediate aftermath of the War’s beginning it did not appear likely to interfere with America’s plans.

However, the decision by Germany to take the war into a new direction challenged this belief.

Unrestricted U-Boat Warfare

Once war was declared, Britain was placed in a difficult position. They lacked an army that could truly challenge the might of Germany. Recruiting a bigger military force would take time. However, the Royal Navy remained the most powerful force on the seas. With this in mind, the Admiralty deployed their fleets to both secure the British Isles against the threat of invasion and also to blockade Germany and prevent ships loaded with supplies reaching the enemy. With this blockade in place, the British hoped to starve Germany into submission over time.

Whilst the German High Seas Fleet was formidable in its own right, risking it in a single battle against the British was not a gamble the German military was yet willing to take.

Instead, they unleashed their U-Boat submarines with instructions to sink shipping that was destined for Britain and France. By doing so they would impose a blockade of their own with the similar hope of starving the British. Germany also declared that the waters around the British Isles were a war zone and that any vessels entering them risked being sunk. This included ships registered to neutral nations.

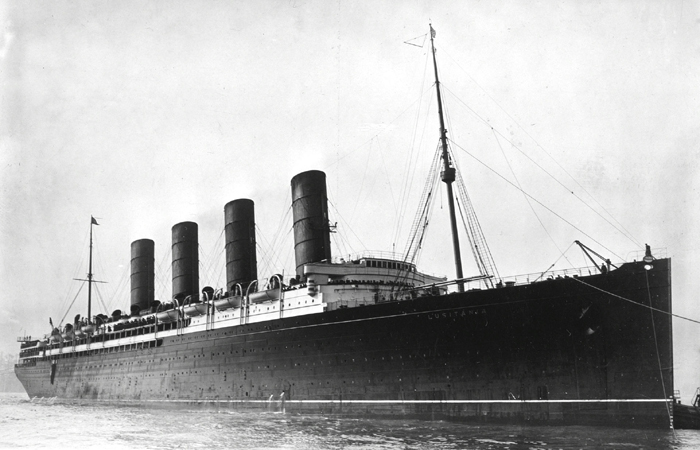

On 7 May 1915, a German U-Boat torpedoed the passenger ship RMS Lusitania of the coast of Ireland. The ship sank in little more than 20 minutes with the loss of 1,198 of the 1,959 passengers. Among the dead were 128 Americans.

The incident caused uproar in America, with Britain and France ceasing upon the opportunity to highlight the apparent barbarity of the Germans. Whilst Germany maintained that the vessel had been a legitimate military target and that it had been carrying munitions bound for France, they also realised that they had greatly angered America and risked dragging them into the conflict.

To try and avoid an American entry to the war, the Germans curtailed the activity of their U-Boats in the hopes of placating neutral powers.

However, by 1916 with the end of the war no closer in sight and the Germans battling hard against the French at Verdun, the decision was again made to widen the activities of German U-Boats in the waters around Britain and coastal France.

On 24 March 1916, a German U-Boat fired torpedoes into the cross-channel passenger ferry SS Sussex. Although the ship did not sink and managed to reach port, around 50 passengers were killed and a number of other civilians were wounded, including 2 Americans. Once again the Germans had raised the ire of the United States and, once again, Britain and France tried to use it as an opportunity to bring America into the war.

This time, the Germans made the Sussex Pledge in an attempt to avoid war. This guarantee ensured that passenger ships would not be sunk, merchant ships would not be sunk without confirmation of military cargo, and that attempts would be made to ensure the safety of any crew or passengers from sunken ships. Once again this assuaged the Americans from intervening.

To try and force a naval resolution to the war, the German High Seas Fleet engaged the British Grand Fleet in the Battle of Jutland over 31 May to the 1 June 1916. However, this battle proved to be non-decisive and the blockade of Germany continued.

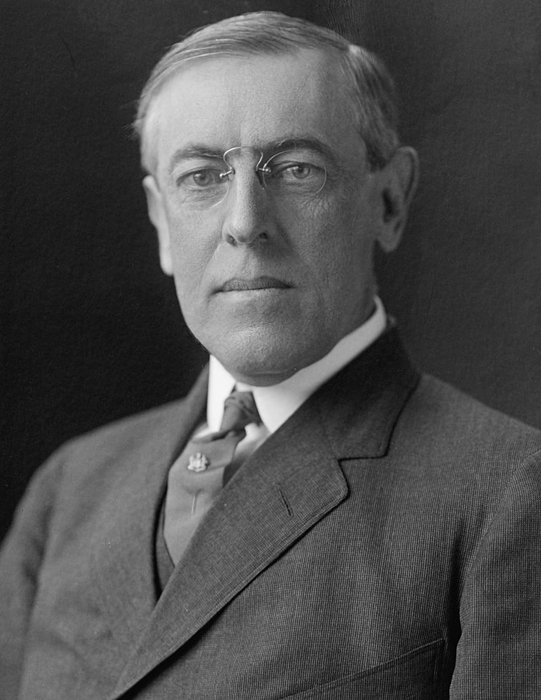

In America, the President throughout the war, Woodrow Wilson was fighting an election in 1916. Whilst the conflict in Europe was becoming an increasingly contentious issue in America, Wilson’s election campaign often painted him as the man who had kept the country out of the war. Wilson’s subsequent victory in this election was seen as an affirmation of his continued policy of non-intervention and neutrality.

The result did little to encourage hopes amongst Britain and France that America might be about to enter the war on their side. In Germany, the heavy losses sustained in the 1916 battles at Verdun and the Somme had impacted the army’s ability to continue fighting. The decision was once again taken to widen the use of U-Boats. However, the Germans were fearful that another incident like the sinking of the Lusitania or torpedoing of the Sussex might be enough to provoke America into war.

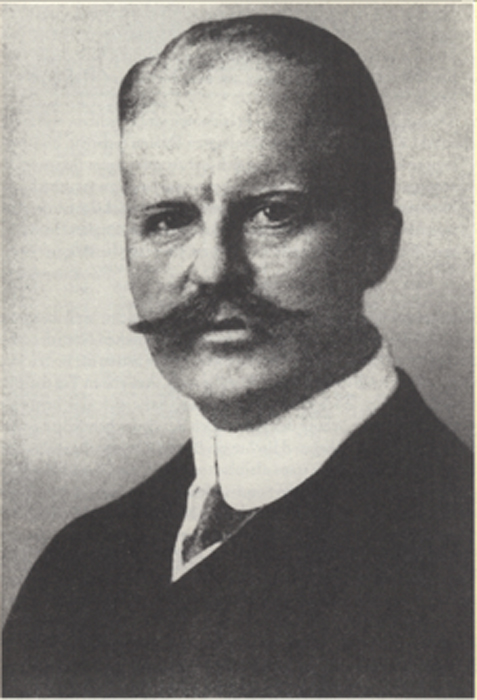

With this in mind the German Empire’s Foreign Secretary, Arthur Zimmerman began to formulate a plan for dealing with any American involvement in the war. His plan would become one of the greatest foreign policy disasters of the 20th century.

The Zimmerman Telegram

It was not the army of the United States that Britain and France were keen to harness, but rather the untapped potential of a nation so large in size and with an industrial infrastructure undamaged by the fighting. The American army for most of the war was only around 200,000 men strong and, as a result comparable in size with the British Expeditionary Force in 1914. However, should the mood cease the country, America’s population was such that a much larger force could conceivably be mustered and sent to war.

For much of 1916, a notable portion of the American armed forces had been engaged against incursions from Mexican bandits, particularly those following Pancho Villa. With the Mexican Civil War ongoing, America still held concerns about their southern border.

These concerns were recognised in Germany and seen as an opportunity.

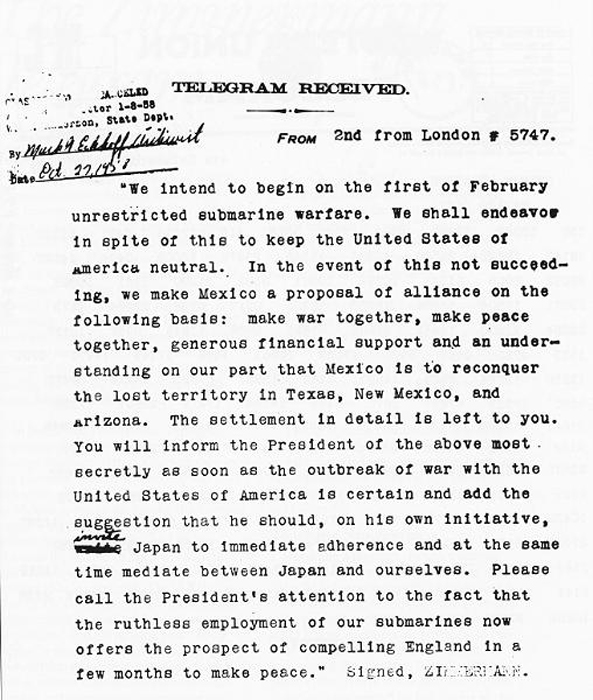

On 11 January 1917, Arthur Zimmerman in his role as Foreign Secretary began the process of sending a secret coded telegram to Heinrich von Eckardt, the German ambassador to Mexico. At the beginning of the war, Germany’s diplomatic cables across the Atlantic had been cut by the British, so Zimmerman’s telegram had to pass through a circuitous route utilising cables in Denmark and Sweden, before using an American cable to cross the Atlantic. The Americans had offered limited use of their diplomatic cables at the start of the war to ensure that communications with Europe and Germany were maintained.

However, for these cables to get across the Atlantic they had to pass through a relay station at Land’s End on the western tip of Britain. Unbeknownst to all parties, including the Americans, all traffic that passed through this relay station was copied and sent to the secretive Room 40 in the Admiralty building in London. Most people had no idea what happened within Room 40 but for those who did, they were aware that it was the very heart of the British cryptanalysis operation. The staff at Room 40 were code breakers.

When the telegram was transmitted through the relay station on 16 January 1917, British intelligence had decoded most of it by the following day. It did not take long for the seriousness of the telegram’s contents to be understood. The British knew that if the Americans were to be shown Zimmerman’s message then public opinion would turn rapidly against Germany and America might push for war. But how could the British provide the Americans with the text without also admitting that they were listening in to all of America’s communications to Europe?

To solve this problem the British held onto the telegram for three weeks whilst they crafted a cover story. They knew that the telegram must have passed through the Mexican telegraph office, so a man identified only as Mr H bribed a member of staff there in order to acquire their copy of the coded message. By itself it was not useful, but the British had also acquired the key for translating this particular code during other battles in the war. They could therefore supply the Americans with both the Mexican copy of the message and the British key for de-coding it, all whilst maintaining their own secret telegram interception system.

Whilst this delay had been ongoing, the Germans had once again declared unrestricted U-Boat warfare in the Atlantic Ocean. This had resulted in America breaking off diplomatic contact. The British sensed that their best opportunity had come.

On 19 February 1917, Edward Bell, the secretary of the American Embassy to Britain, was shown the following translated telegram:

“We intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. The settlement in detail is left to you. You will inform the President of the above most secretly as soon as the outbreak of war with the United States of America is certain and add the suggestion that he should, on his own initiative, invite Japan to immediate adherence and at the same time mediate between Japan and ourselves. Please call the President’s attention to the fact that the ruthless employment of our submarines now offers the prospect of compelling England in a few months to make peace.” Signed, ZIMMERMANN

At first Bell refused to believe the message was real but upon being assured of its legitimacy he flew into a fury. The following day the message was shown to the American ambassador, Walter Hines Page, and then sent on to President Wilson. Wilson subsequently released the text of the message to the American press on 28 February.

At the time, there were still strong anti-Mexican sentiments within America which were further inflamed by the German telegram. The Mexicans quickly disavowed themselves from the German offer, having made their own assessment of the situation and whilst they might have wished to recapture the territories of Texas, New Mexico and, and Arizona which they had lost to America in differing circumstances such as the Mexican-American War and the Mexican Cession they were not blinded to the difficulties in achieving this. Mexico realised that not only was it unlikely that they could reconquer these lost lands, there were no guarantees that the Germans would be able to offer what they promised. There was also little chance that the Mexican government could influence Japan to do anything, let alone engage in war against America. However, whilst President Wilson was convinced as to the message’s veracity, because the newspapers reported the British cover story of the telegram being stolen from a Mexican telegraph office, many people believed it to be a forgery perpetrated by the British to gain American support in the war.

These concerns from the public may yet have stopped American entry into the conflict until Zimmerman once again took centre stage. In a press conference on 3 March 1917, Zimmerman was questioned by an American reporter on the telegram and its contents, only to declare; “I cannot deny it. It is true.” At the end of the month he then gave a speech in the German Reichstag once again admitting the telegrams authenticity and his role in crafting it. He hoped to assuage the Americans with the assurance that the message would only have been enacted if the Americans had declared war. It didn’t work.

With U-Boats once again active in the Atlantic, and two American ships being sunk in February, combined with a German attempt to incite Mexico and Japan to wage war against America, public opinion ferociously turned against Germany. At the same time, France had dispatched Marshal Joseph Joffre, former commander of the French army, to lead a mission designed to boost popular opinion in favour of the Entente Alliance. Joffre emphasised the shared revolutionary and republican heritage between America and France and effectively charmed large numbers within the populace.

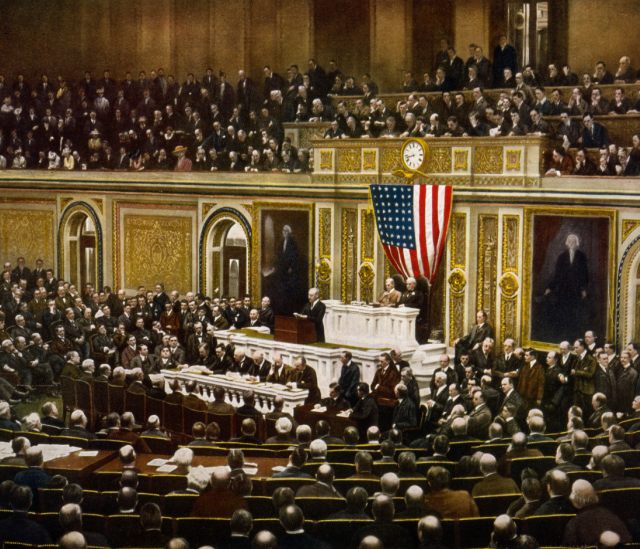

On 2 April 1917, President Wilson called a special session of Congress. In his speech he declared that ‘the World must be made safe for peace and democracy‘ and asked that Congress vote to declare war on Germany. On 6 April 1917, Congress voted overwhelmingly to support President Wilson’s request and a state of war was declared between the United States of America and Germany.

All that Zimmerman had hoped to avoid, had come to pass.

Aftermath

Whilst America was now at war it was not ideally suited to it. Building a new army would take time even with British and French assistance.

In Europe, the recent Russian Revolution and subsequent peace treaty between them and Germany had removed the Eastern Front from consideration. Germany was able to refocus all its efforts towards the Western Front and the fight against Britain and France. The Germans knew that whilst it would take the Americans time to build momentum, if the war were not quickly won then doing so would become impossible.

At the end of March 1918, the Germans unleashed their Spring Offensive, beginning with Operation Michael. These attacks were designed to split the British and French armies apart, drive towards Paris and win the war. At the time, the American army in Europe only numbered 284,000 men.

However, the German army was exhausted and despite impressive success in the earliest days and weeks of the offensives they could not claim victory.

Even worse, the Americans were beginning to arrive in increasing numbers. By 30 July 1918, the American army numbered 1 million men. By the start of November it would be 1,872,000. At one point over 10,000 Americans were arriving in Europe every day.

Against such numbers, and faced with a resurgent British and French military whilst their own army was beaten and exhausted, the Germans realised they could not win and began the process of seeking peace.