13th Battalion ‘SouthDowns’ at Cooden in 1915. Image courtesy of Paul Reed, Great War Photos www.greatwarphotos.com

When war was declared in 1914, Britain found itself short of soldiers. Men would have to be found and motivated all across the country, and East Sussex was no different. This is the story of how Claude Lowther recruited hundreds of men and sent them off to war. Many would not return home.

The sight of Lord Kitchener pointing out of a poster calling men to arms remains one of the enduring images of the First World War. At the outbreak of war in 1914, Britain was faced with the pressing need to build an army that was capable of fighting a continental war. To achieve this recruitment activities had to take many forms in order to reach, and secure, the most men.

When Britain issued its declaration of war against Germany on 4 August 1914, the British Expeditionary Force that represented the might of the British army was just over a hundred thousand men strong. It has popularly come to be believed that the outbreak of war saw young men ‘rush to the colours’ all eager to do their part. This is not entirely true however. Mass recruitment did not reach its peak until the end of August and early days of September, when first the London Gazette and then The Times printed a dispatch from the Battle of Mons. This battle had seen the British and French armies driven back in retreat ahead of the advancing Germans. The ‘Mons Dispatch’ reported that defeat was now a very real possibility.

It was only when the war looked lost that men began to volunteer in huge numbers. By the end of August, more men were joining the army each day then they had in the first week of the war. Over 20,000 men joined the army on 31 August. By 3 September there were over 33,000 men joining a day.

This was not just a national movement. It was played out in microcosm in the streets and towns of East Sussex. In order to achieve this a variety of appeals aimed at bringing men into the army began to appear, but each one was carried out in a slightly different manner.

In the years before the war, service in the army had not been seen as particularly auspicious. Britain relied on its navy to defend both the country and the Empire, so had no real need for a large army like those found on continental Europe. As a result, there were a variety of fears and concerns that had to be addressed in order to reach the general population and move the men to recruit.

Recruitment in Sussex

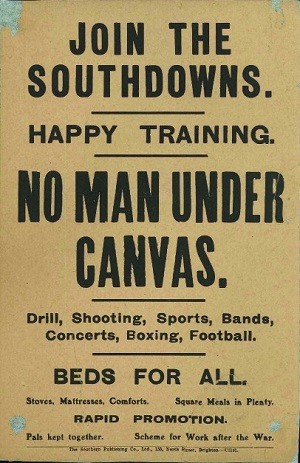

Recruitment posters show how some of these were confronted. Sussex men did not want to join up for the army only to be left bored in training camps or pitched in tents on farmland or parks, as was the case in other areas of the country. The army was sold to them as a chance to truly ‘be men’ and an aspect of that was the opportunity for sporting and martial contests as well as the opportunity to advance in rank if you proved yourself skilled or worthy.

Similarly, men wanted to avoid having to pay for their own uniforms and army kit. Indeed, men wanted to receive some form of uniform as quickly as possible so they could be seen to have joined up and appear soldierly.

Sussex also benefited from having a recognisable landscape that could be incorporated into recruitment imagery. One poster featured a kilted soldier with, no obvious link to Sussex, standing before a utopian rural landscape that resembled various aspects of the British countryside including the South Downs and declared this area to be worth the price of battle and possibly death.

Recruiting map of the Southdowns Battalion. Hastings and St leonards Pictorial Advertiser 10 December 1914.

Recruitment posters were not the only method of securing the services of men in East Sussex. The rise of Pals Battalions at the outbreak of war gave men the chance to sign up and serve alongside their friends, family, and co-workers. As an idea for solving the recruitment shortage Pals Battalions were extremely successful in 1914. Of the total 115 Pals Battalions raised during the war, 85 of them were in 1914.

Claude Lowther

Claude Lowther was a Conservative Politician and owner and resident of Herstmonceux Castle in 1914. At the outbreak of war he raised ‘The Southdowns’; the 11th, 12th, and 13th Battalions of the Royal Sussex Regiment.

Lowther was a recognised and respected figure in the community and was able to receive permission from Kitchener to raise his battalions. He did not just rely on posters however. He sought out other men well regarded in the community such as Neville Lytton and empowered them to raise men too. Lytton travelled the county in a car, often accompanied by a doctor, and went house to house in his search for men willing to join the army. At the end of this process, Lytton arrived in Eastbourne with 150 men destined for the battalions.

Whilst Lowther temporarily held the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel, like many others who had raised battalions in this manner, he did not lead them to France himself. He returned to Herstmonceux Castle once his work was completed.

The battalions he had raised bore the unofficial title of ‘Lowther’s Lambs’, men of the Southdowns who had joined up together to fight together and became part of the wider Royal Sussex Regiment. In time they would be deployed to the Western Front and Lowther’s Lambs saw their first sustained action on June 30 1916, the day before the Somme. Many of them would not return home.

Sources

Eastbourne’s Great War 1914-1918 by R. A. Elliston

East Sussex Record Office, The Keep

Imperial War Museum Archives, London

Sussex in the First World War by Keith Grieves

The Day Sussex Died: A History of Lowther’s Lambs to the Boar’s Head Massacre by John A. Baines

The Last Great War by Adrian Gregory

www.greatwarphotos.com by Paul Reed

The Press and the General Staff by Neville Lytton