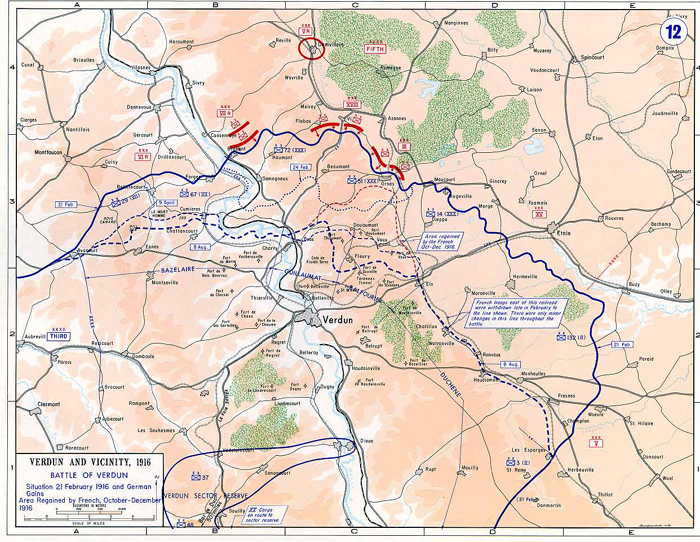

Did you know that the longest running battle of the First World War began on 21st February 1916?

The battle between the French and Germany armies near the fortress city of Verdun lasted for nearly 10 months during 1916 and, by its conclusion, had resulted in over 700,000 casualties.

The Fortress City

Situated to the east of Paris, Verdun had defended the route to the French capital for centuries. The town of Verdun lay on the River Meuse and had historically come to be considered as crucial to the defense of both Paris and the heart of France itself. By the beginning of the First World War the long-standing citadel at the centre of the town had been surrounded by a series of large concrete bunkers. The most significant of these were the forts of Douaumont and Vaux.

However, early in the war the French military had reduced both the number of guns and the number of defending soldiers at Verdun in order to strengthen other areas of the front. It was a decision that would have nearly fatal consequences.

At the end of 1915 the German military had decided to launch an attack on Verdun for the start of the following year. In charge of this attack would be General Erich von Falkenhayn. The actual aim of Falkenhayn’s attack remains contentious even today. In many ways 1916 was the year of ‘attrition warfare’ – the act of wearing down an opponent’s army and inflicting as many casualties as possible over a period of time whilst preserving your own force. With this theory in mind, Falkenhayn’s objective is often suggested to be the slow destruction of the French army in order to force them to make peace and, as a consequence, rob Britain of its strongest ally.

By launching the attack at Verdun, such a potent French symbol, it is claimed that Falkenhayn knew the French would not be able to abandon the city and would be forced to fight continually to defend it. As a result the Germans would be able to ‘bleed France white’.

By the time the French realised that Verdun was about to be attacked they were almost too late to adequately prepare. However, bad weather delayed the German offensive from 12th to the 21st February, thereby giving the French the extra time they desperately needed. Despite this, however, the German attack was to have fearful repercussions.

Douaumont and Vaux

The German artillery opened fire at 7:15am on 21st February 1916 and over the course of ten hours fired over one million shells before the German infantry attacked. German soldiers carrying flamethrowers and hand grenades seized French trenches and, by the end of the day, had traveled over three miles towards the city itself whilst receiving negligible casualties.

By 25th February the German infantry had reached the mighty fortress of Douaumont. Finding the guns at the fort strangely silent small parties of German soldiers entered the huge building. Inside they found a small group of French soldiers and maintenance staff. In the confusion leading up to the initial German attach, the French military had neglected to rearm the fortress and return it to the normal compliment of defenders. As a result the key feature of the defenses around Verdun had been left empty and toothless and was captured with barely a shot being fired.

If Falkenhayn had wanted to ensure that the French would not abandon the battlefield at Verdun he ensured it with the capture of Douaumont. The fall of the fortress caused uproar in France and popular opinion demanded that the town be defended and the fortress retaken.

- For Douaumont before the First World War

- For Douaumont after the First World War

- The defenses of Douaumont today – Image courtesy of Chris Kempshall

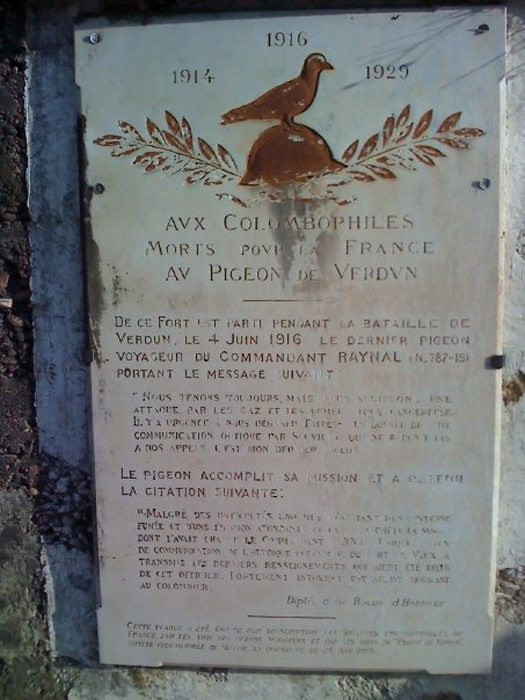

Morale was only to fall further when, in June, the Germans successfully captured Fort Vaux from the French defenders. Unlike Douaumont, Vaux had been adequately defended but, with German troops coming to surround the position and food and water running out the French defenders were slowly sieged into surrender. The French commander dispatched a homing pigeon named Valiant with a desperate message:

‘We are still holding. But … relief is imperative. Communicate with us by Morse-blinker from Souville, which does not reply to our calls. This is my last pigeon.’

Memorial Plaque to Valiant; the pigeon who tried to save Fort Vaux – image courtesy of Chris Kempshall

Having been badly gassed and wounded Valiant succeeded in delivering its message before dying. However, despite this, no French assistance could be sent and Vaux too was captured by the Germans.

Beyond Verdun

The ferocity of the German attack at Verdun had taken the French almost by surprise and would lead to dramatic changes in strategy for the rest of the year. Planning for the British and French attack at the River Somme had begun at the end of 1915 but now, with so many French soldiers needed to defend Verdun, the British army would have to take on more of the responsibility for their coming attack.

The British launched diversionary attacks before attacking on the Somme in an attempt to draw German soldiers away from both that battlefield and the fighting at Verdun. One of these diversions would have terrible consequences for East Sussex.

However, whilst the opening of the Battle of the Somme was disastrous for the British, the effort required from Germany to defend against the British to the north whilst also fighting the French at Verdun proved almost impossible to maintain.

Defeat and Aftermath

With the Germans struggling to maintain their efforts at both the Somme and Verdun, the French took the opportunity to launch a series of powerful counterattacks.

The Fort of Douaumont was badly damaged by an internal fire in May 1916 and the French pushed to recapture it throughout the autumn. Eventually, after days of heavy fighting, the Germans abandoned the position and it was recaptured by the French on 24 October. Within a week a French patrol found that the fortress at Vaux had also been abandoned by the Germans and it was recaptured without needing to fight.

By the time the battle ended on 20th December 1916 the Germans had lost all of the territory they had gained earlier in the year and the area around Verdun had been utterly devastated by nearly ten months of constant fighting.

During the course of the battle the French had suffered in the region of 377,000 casualties of which 162,000 were killed. The Germans had fared only marginally better with 337,000 casualties with around half of these men also losing their lives.

Today the area around Verdun contains many cemeteries to the fallen soldiers. The fortresses of Douaumont and Vaux are both largely still standing and an enormous monument known as the Douaumont Ossuary stands at the site of the former. Within its walls lie the remains of thousands of French and German soldiers, whilst thousands more French soldiers lie buried outside. Closer to the town of Verdun itself is a national cemetery of French soldiers who defended the town. The ferocity of the fighting at Verdun has left the countryside around it scarred and cratered even until this day.

- The view from the top of the Douaumont Ossuary – Image courtesy of Chris Kempshall

- The view from the top of the Douaumont Ossuary – Image courtesy of Chris Kempshall

- The French National Cemetery at Verdun – Image courtesy of Chris Kempshall

- A German cemetery near Verdun – Image courtesy of Chris Kempshall

In tactical and strategic terms the Battle of Verdun had seemingly achieved very little, with both armies in control of the same territory as they had been previously. However, the sheer number of casualties and the apparently cynical nature of Falkenhayn’s plan had not only badly wounded the armies of both France and Germany but also hardened the will of both nations to fight to the last.

After enduring such horrors and sacrifices, there could be no peace without victory.