Did you know that Britain, France and America sent the first proposals for a peaceful settlement with Germany on 5 November 1918?

Germany had already made tentative enquires as to the possibility of making peace through America on 4 October 1918. They were particularly interested in making a peace based on President Woodrow Wilson‘s Fourteen points. However neither Britain nor France were willing to accept a peace on such terms and the three principal allied nations were forced into a negotiation among themselves over the terms with which they would be willing to discuss peace with Germany.

Germany’s major allies were already beginning to make peace as they were no longer able to continue the war and had no hopes of winning it. Austria-Hungary signed their own Armistice on 3 November 1918, Turkey had done the same on 30 October whilst Bulgaria had surrendered on 30 September.

There were numerous obstacles to overcome in simply commencing armistice talks with Germany, let alone concluding them. Not least was the American demand that any peace process had to include the abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II. However, the situation in Germany was already deteriorating massively. The German Navy had been ordered to sea on 24 October to force one last showdown with the Royal Navy. This sparked a mutiny that had rapidly spread from Kiel, Northern Germany, and by 7 November many of the major port towns along the German coast were declaring revolution.

On 8 November, a German delegation was brought to a quiet railway siding in France. They had left their own lines several days beforehand and were taken on a circuitous trip through France until reaching their destination. None of them was sure who was left in charge of Germany in Berlin or if they still had the power to negotiate at all.

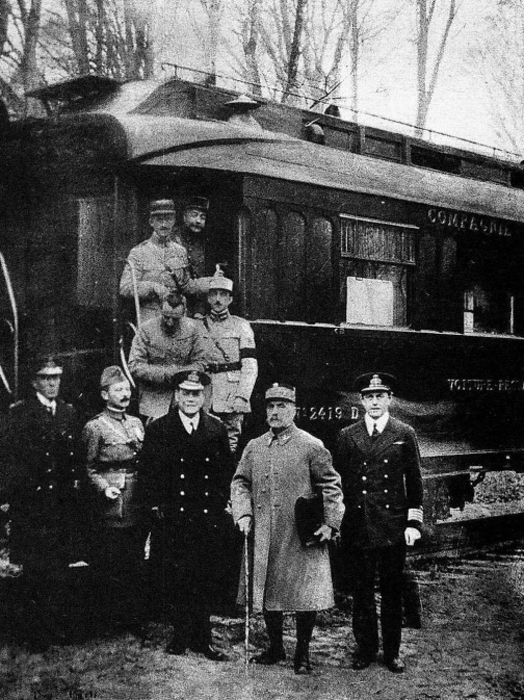

Upon their arrival on the morning of 8 November the Germans had been expecting a dialogue. They were greeted by the Allied Supreme Commander Marshal Ferdinand Foch whose first words to them were; “What do you want of me?” The response that they had come to listen to Foch’s proposals for an end to the war was met with the declaration that he had no proposals to make. If the Germans wanted an armistice he was empowered to give them the allied terms but this was not to be a process of negotiation.

The thirty-four clauses the Germans were presented with drained the colour from their faces and caused several of the party to break into tears. They retreated to their own carriage and explained they would have to send a messenger back to their army command in order to get the approval. Foch gave them 72 hours to get authorisation and sign the agreement. The Germans would not see Foch again during the negotiations until the day they signed the agreement.

In Germany, the Kaiser waited near the Imperial Army Headquarters near Spa in Belgium, close to the Dutch border, whilst attempting to make up his mind over whether to abdicate. In the end the decision was taken for him. With revolutionaries marching through the streets of Berlin, the Chancellor Prince Maximilian of Baden preemptively announced that the Kaiser had abdicated in an attempt to prevent the crowds storming the Reichstag. When word of this reached the Kaiser, he was convinced by his remaining loyal army officers that he had to abdicate and flee across the Dutch border into exile. By 10 November, he was gone.

The German peace delegation spent much of the next few days waiting for a response from a military and governmental command that barely even existed anymore. Their messenger had spent most of the first day trapped in French trenches being prevented from going back to his own side of the line by German soldiers who refused to stop shooting at him.

When approval from Germany finally was communicated to their delegation, it was broadcast via radio without encryption and stated that ‘The German government accepts the conditions of the Armistice’. The method of transmission effectively invalidated the few concessions the Germans had managed to extract from the allies over the preceding days.

The delegation gathered again in Foch’s railway carriage in the early hours of the morning of the 11th. The armistice was signed at around 5:13am (French time). For official purposes, Foch suggested the time of signing should be rounded down to 5am and that there would be a 6 hour window before it came into affect to allow word to spread to the men at the front. The time for the armistice to commence was therefore set for 11am French time. The Germans agreed and then read a prepared statement protesting the harsh terms forced upon them.

‘Tres bien’ was Foch’s disinterested response. There were no handshakes following the signing; the men posed for a single photograph before the two groups took possession of the signed documents and maps and began to disperse towards Spa, Paris and London.

Sources

Nicholas Best – The Greatest Day in History: how the Great War really ended