On 1 July 1916, British and French forces attacked German positions along the River Somme in what has become one of the most infamous and controversial battles of the First World War.

The Battle of the Somme marked the beginning of the British and French contribution to what has become known as the Grand Allied Offensive of 1916. However, the path to the Somme was marked by difficult negotiations between the participants and hindered by German attacks in early 1916.

The Chantilly Conference

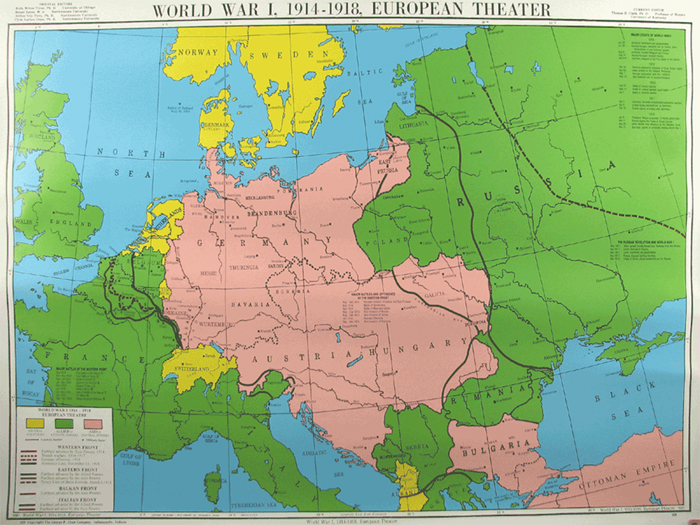

By the end of 1915, both Britain and France had made multiple attempts to breach the German lines only to sustain huge casualties and achieve little notable success. With the clear realisation that the war was now likely to stretch on into 1916, the different nations that comprised the Entente alliance, France, Britain, Italy, Russia, and Serbia, gathered at Chantilly in Paris from 6th-8th December to plan their strategy for the year ahead.

Between these countries it was decided the best path forward was to co-operate in what would come to be known as the Grand Allied Offensive of 1916. In essence, each of the allies would commit to an attack against the forces of Germany and Austria-Hungary during 1916.

These multiple attacks would help wear down the enemy numbers by forcing them to defend on all fronts. By coordinating these attritional attacks the allied forces would soon destroy the combined armies of their enemy without causing irreparable damage to their own. Russia agreed to attack Germany and Austria-Hungary from the east. Serbia agreed to attack from the south-west, with Italy attacking from the South. Britain and France agreed to a joint attack on German lines from the west.

The British-French plan proved to be the most complicated and controversial aspect of these negotiations. Since the beginning of the War the French had borne the bulk of responsibility for fighting on the Western Front. This had resulted in them sustaining heavy casualties throughout 1915, and they were now keen for Britain to begin sharing the burden. The British had, through mass recruitment of willing civilians, managed to raise a substantial new fighting force referred to as Kitchener’s New Army. Lord Kitchener, however, had wanted to save this fighting force until 1917 when it could be fully trained and then play a decisive role in winning the war. As a result, the British were unwilling to commit this new force without the French also sharing the offensive duties. The French weren’t willing to fight any more battles alone and insisted on British participation as well.

These requirements resulted in an agreement to launch the attack around the River Somme. Whilst not strategically important, the location did have the benefit of being the place where the British and French armies met. This meant that both could attack and rely on the other to do the same thing.

No sooner had the rough outline of the assault been agreed between the French General Joseph Joffre and Britain’s General Sir John French on the 8th December, then Sir John French was replaced as the British commander by General Sir Douglas Haig. General Haig had always favoured an attack in Flanders, Belgium in an attempt to capture German U-Boat pens and secure the channel ports.

More negotiations were required but agreement was finally achieved on 14th February 1916, for a planned attack along the Somme in July of the same year.

One week later the preparations for 1916 were dramatically changed.

Verdun and plans for the Somme

On 21st February 1916, the German’s launched an all out attack on the French fortress city of Verdun. The fighting at Verdun would become the longest-running battle of the entire war. By the end of May the French announced that, due to the casualties being sustained at Verdun, they could no longer participate at the Somme in a 50-50 battle with the British. As a result the French involvement in the battle was dramatically scaled down and the British took up a greater section of the front line than had originally been intended.

Whilst relieving the pressure on Verdun was not one of the original objectives for the planned Somme attack, the General Joffre now made it clear that the British must press ahead with the attack or risk the slow destruction of the French army.

The two British generals in charge of the planning for the Somme were Douglas Haig and Henry Rawlinson, with Haig holding the senior role. Much of the controversy that has followed from the Somme Offensive stems from the seemingly mixed objectives that Haig and Rawlinson claimed for the battle. The original operational objective, aside from to help destroy significant sections of the German Army, was to assist the French Army in crossing the river near Péronne.

However, additional objectives were also considered and rose and fell in favour. Haig began pondering the possibility of actually breaking through the German lines and into the open ground behind. Such a breakthrough would threaten the entire German Army and could dramatically shorten the length of the war. This potential objective did not sit comfortably alongside the fact that both Haig and Rawlinson seemingly had differing concerns over the ability of their new soldiers to carry out anything but the most simple of orders.

Additionally, whilst the British section of the front line had increased, Haig did not scale up his artillery contribution to match it. The British had a significant number of artillery pieces arrayed around the Somme, but they were now being forced to cover a much larger area with fire than had previously been planned.

Three 8 inch howitzers of 39th Siege Battery, Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA), firing from the Fricourt-Mametz Valley during the Battle of the Somme, August 1916. – Image Courtesy of Imperial War Museum: Q 5818

On the 24th June 1916 the British and French began a preparatory artillery bombardment of German trenches. The aim of this bombardment was to destroy German trenches and barbed wire to such an extent that the attacking infantry would easily be able to capture enemy positions. It was also believed that the bombardment would break German morale and leave the surviving soldiers with little ability to resist the attack. Originally scheduled to last for 5 days, bad weather extended it to a full week. The bombardment was the heaviest in history at that point and could be clearly heard from the south coast of England.

The British also staged diversionary attacks on other parts of the Western Front to try and draw German soldiers away from the Somme.

When the guns stopped on 1st July 1916, British and French soldiers went over the top.

The First Day of the Somme

At 7:20am on 1st July 1916, the British Army detonated stacks of explosions that had been tunnelled beneath German trenches. These explosions were so loud they rattled windows in London. These explosions, timed for 10 minutes before British and French infantry would attack, marked the beginning of what we now consider to be the Battle of the Somme.

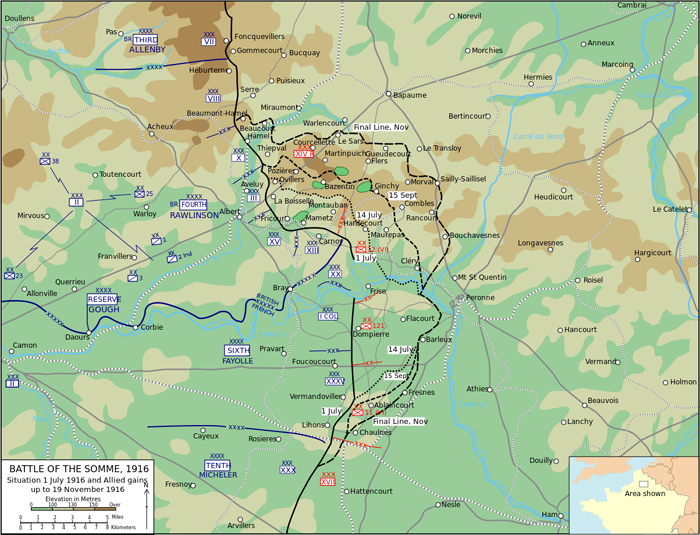

At the south end of the front line where the British and French armies met most objectives were easily captured on the first day. The French Army at the Somme was commanded by General Ferdinand Foch, a man who would play a key role in the war ending in 1918. After years of fighting the French Army was highly accomplished and British soldiers benefited from sharing the area with them. More to the point, the French had placed as much artillery as they could spare on their front line and used it to destroy a small area of German defences so that infantry could easily capture enemy positions.

Further to the north, however, things were going badly.

In previous artillery bombardments it had been thought that shrapnel shells were best at cutting barbed wire. It wasn’t until British infantry discovered lines of undisturbed barbed wire when they approached German trenches on the morning of the Somme that this was found not to be true. Additionally, the German troops on the Somme had been living in well-constructed underground bunkers. As a result the majority of German troops were entirely unharmed by the week long artillery bombardment.

Additionally both Haig and Rawlinson had been so unsure as to what the partially trained British Army would be capable of they settled on keeping orders as simple as possible. Infantry were ordered to maintain a slow but steady pace across no man’s land and soldiers were told to keep in line with the men on both sides.

A support company of an assault battalion, of the Tyneside Irish Brigade, going forward shortly after zero hour on 1 July 1916 during the attack on La Boisselle. – Image courtesy of Imperial War Museum: Q 53

The British waited for 10 minutes after the detonation of their underground mines to ensure that there were no secondary explosions. At 7:30am they went over the top all along the line and began crossing towards German trenches. At the same moment German soldiers began to fire down upon the lines of British troops walking slowly uphill towards them.

The British began to take such casualties that their own front line trenches became blocked so subsequent attacks had to go over the top from trenches further away from the German lines. These trenches were still in range of German machine guns and artillery so they too because swiftly blocked.

By the end of the day a disaster had played out across the British lines. Many Pals Battalions had attacked at the north end of the British lines where German resistance had been strongest. The resulting casualties meant that towns lots hundreds of men.

Smaller nations within the British Empire also attacked on the Somme. The tiny dominion of Newfoundland had a population of 240,000 before the outbreak of war. In 1914 they had committed 1000 men to the British army but a number of these had been lost fighting in 1915 and had to be replaced. On 1st July 1916, 22 officers and 758 men of the Newfoundland regiment attacked on the Somme. By the end of the day all of the officers and 658 of the men were casualties. Only 110 men in total survived and only 68 of those were fit enough to attend roll call the following morning. The casualty rate for the Newfoundland regiment on the first day of the Somme was 90%.

By the end of the day 57,470 British soldiers had become casualties and 19,240 of those were dead. It remains the worst day in the history of the British Army.

After the first day.

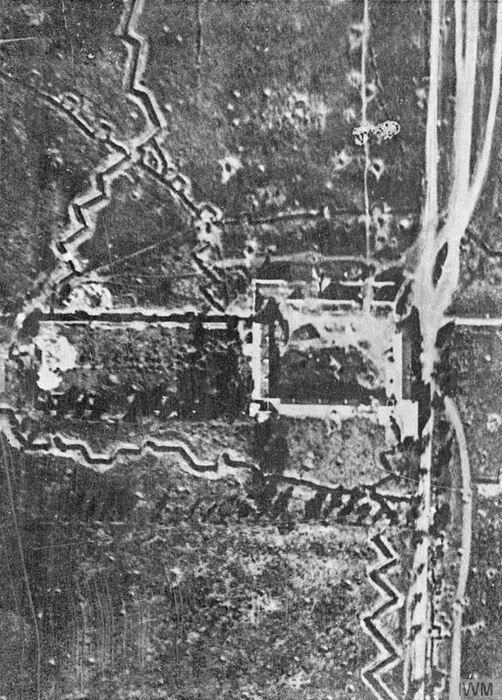

Mouquet Farm, near Thiepval with trench systems surrounding it, prior to 1 July. – Image courtesy of Imperial War Museum: Q 27637

It became clear that the first day had been a disaster, with very little gained from any of the attacks north of the river. The British and French had to now decide how best to press on with their attack. To the south, where the British and French armies met, heavily defended German positions at Guillemont had slowed their advance. To the north, the German defences at Thiepval Ridge were able to continue firing down on British attacks.

The allies had to continue the attack but began to investigate more inventive ways of doing so.

On 14th July, two weeks after the first day of the Somme, the British staged a surprise night attack at Bazentine Ridge. Just after 3am British soldiers silently crawled from their trenches into no man’s land. Then, at 3:20am, British artillery launched a 5 minute heavy attack. As soon as the guns had stopped, British infantry rose from no man’s land and dashed into German trenches almost unopposed.

The battle itself would continue to run on for months as British, French, and German casualties continued to mount.

The high point for the British came on 27th September when, finally, they captured the German position at Thiepval. The French came to regard this as the moment when the British became capable of operating independently on the Western Front and it also dealt a tremendous blow to German morale.

Various portions of the battle had been filmed by British cameramen and millions of civilians back home visited cinemas to glimpse the action.

New British weapons called ‘tanks’ also made their debut on the Somme battlefields.

Aftermath

When the battle came to a close at the end of November all sides began to take stock of their losses.

The British had sustained 419,654 casualties up to 30th November. The French Army at the Somme had sustained 202,567 casualties by 20th November.

German casualties are harder to ascertain but from January to October 1916 the German Official History of the war puts their total casualties (including from both the Somme and Verdun offensives) at 1.4 million. 800,000 of these casualties came after July. German casualties around the Somme were probably in the region of 500,000 men.

Whilst the Grand Allied Offensive of 1916 had placed extreme pressure on the combined armies of Germany and Austria-Hungary, the hoped for collapse in these armies had not materialised.

As a result the war would have to continue into 1917 with all sides having been weakened by their exertions.

Many of the bodies of British soldiers who died at the Somme were never recovered. The names of 72,000 men who have no known grave are today commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing.