During the First World War, the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) first began operating in March 1917.

As the First World War dragged on into 1917, ongoing shortages of men and soldiers began to impact Britain’s ability to continue the conflict. In the early years of the war, as men had left their civilian jobs to join the army, the shortfall had been filled by women entering the workforce. Occupations such as the postal and transport services had been particularly hard hit.

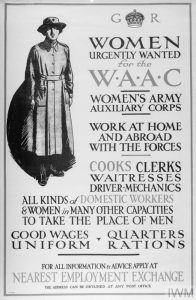

Ministry of Labour poster for the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps – Image Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum (IWM Q 68242)

However, with conscription implemented to force eligible men into military service there was still no end to the conflict in sight. To maintain Britain’s fighting forces, new organisations would need to be created to help harness the ability of the female workforce.

Since the outbreak of the war, women hadn’t simply moved into previously male occupied roles; dedicated organisations had been founded or expanded specifically designed for women’s participation. The Volunteer Aid Detachment for female nurses had existed since 1909 but grew in size throughout the war. The first branches of the Women’s Institute had begun to appear during 1915. The start of 1917 saw the creation of the Women’s Land Army to maintain Britain’s agricultural interests.

Whilst these various emerging organisations participated in important war-related work, they were not permitted to function in a military manner. Evidence had been growing as the war continued that some women would happily join organisations structured along military lines, but neither the army, nor the societal gender roles of the time would allow for it.

The WAAC was the official attempt to forge a form of compromise. The WAAC was first founded on the 28th March 1917, though it would not be formally instituted until July of the same year. The WAAC became the first example of a Western nation employing women within the armed services. The primary rationale behind the creation of the organisation was to ‘comb out’ men working in non-combatant or administrative roles within the army. By placing women into these jobs the men previously occupying them could be redeployed into combat roles.

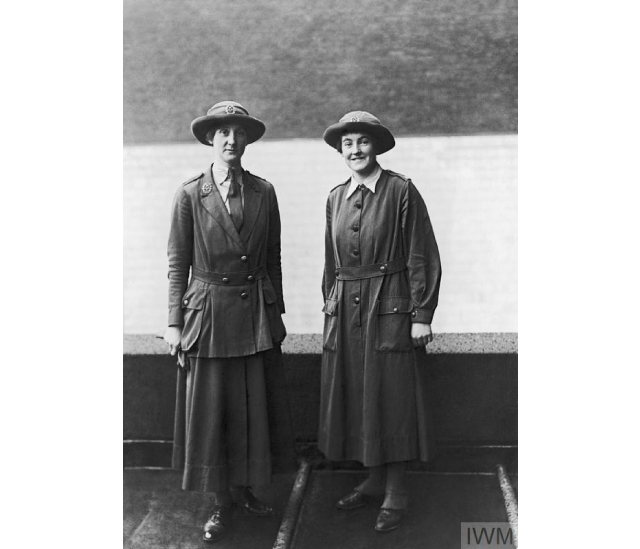

A WAAC cricket team at Etaples, 1 May 1918. – Image Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum (IWM Q 8754)

As a result, women, for the most part, were employed in 5 broad ranging occupational groups: clerks, domestic services, mechanical maintenance, cookery and tending war graves. The latter of these occupations was believed to be especially suited to women as an extension of their role as nurturers and carers in civil society. However, in keeping with the policy of ‘dilution‘ that existed for jobs in the civilian sector, positions previously filled by a single male worker were spread across two or three women, to ensure that none of them could act as an outright replacement independently. Despite this, the activities of the WAAC were sometimes filmed by the military for newsreels for the general public. One such film is available to be watched through the website of the Imperial War Museum.

Whilst women in the WAAC wore a form of military uniform and existed within the military institution, great lengths were made to ensure that they could not be considered a combat organisation. Military ranks were forbidden from use within the WAAC and instead of officer titles, women in command were referred to as ‘Controllers’ and ‘Administrators’. Women of the lowest rank, nominally a ‘Private’ in the army, were simply referred to as ‘Worker’. Similarly, badges of rank were not allowed to follow military norms and instead were replaced by fleur-de-lis symbols and flowers, such as the rose.

Women joined the WAAC from across the country. One of the many who served in the organisation from East Sussex, was Iva Mary Harland from Framfield. Several members of the Harland family had become caught up in the conflict, with Iva serving in the WAAC, and William John Harland served in the Royal Engineers. Sadly, both of them would lose their lives before the Treaty of Versailles could be signed. Iva Mary Harland died at home on 28th February 1919, at the age of just 23. William died in the Salonika campaign in 1917.

Following her death, Iva was buried and commemorated in the graveyard of the Saint Thomas-a-Becket Church in Framfield.

On 31st March 1917, the first members of the WAAC were sent to France to begin work there. By the beginning of 1918, over 6,000 WAACs were serving in France. Following the American entry to the war, a sizeable contingent of WAAC members were assigned to the American Expeditionary Force to further supplement their workforce.

In April of 1918, the organisation was renamed as the Queen Mary Army Auxiliary Corps (QMAAC). By the conclusion of the conflict the QMAAC had 57,000 women enrolled in service. The organisation would not be formally disbanded until 1921.

Sadly, many of the records for the organisation were lost in an air raid in 1940. However, what records do survive can be accessed through the National Archives.