On 21 March 1918, the German army launched an offensive on the Western Front designed to bring the First World War to a conclusion. Though it would push Britain and France to the brink of defeat it would eventually result in Germany losing the war.

By the end of 1917 the situation on both Western and Eastern Fronts of the First World War had changed dramatically. Repeated revolutions in Russia had overthrown the Tsar and set in motion the creation of the Soviet Union. In a bid to shore up power, Vladimir Lenin was prepared to sign a peace treaty with Germany and end the conflict on the Eastern Front.

The battles of Verdun and the Somme in 1916 had gravely weakened the armies of Britain, France, and Germany in the west. Britain would attempt to force Germany back again in 1917 during the Third Battle of Ypres. In an attempt to starve Britain into submission in 1917, Germany had once again launched a campaign of unrestricted U-Boat Warfare breaking their 1916 ‘Sussex Pledge‘. Germany knew that such a course of action may provoke the President of the United States, Woodrow Wilson, who had only recently won re-election.

To prevent American interference in the conflict, Germany hatched a plot which would see them offer military support to Mexico for an invasion of America if the United States declared war on Germany. However, the leaking of this secret plan through the infamous Zimmerman Telegram infuriated the Americans and led them to declare war regardless.

Germany now faced a strategic and mathematical conundrum. They knew that with Russia on the verge of quitting the conflict, they could relocate men from the Eastern Front to face Britain and France and have a numerical advantage. However, with American soldiers beginning to arrive in 1917, this advantage would not last for long. Though the German army was tired, there was a chance that one final successful attack could bring the war to an end.

Operation Michael

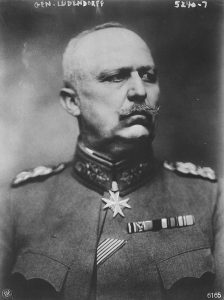

The German general Erich Ludendorff considered several plans for the opening of their Spring Offensive and eventually settled on an attack near the town of St Quentin. Whilst the geography of this area, being near the old Somme battlefield of 1916, was not conducive to a full-scale assault it did provide a notable benefit. This was the area where the British and French armies met on the Western Front. If the Germans could drive them apart they could isolate the British in particular and potentially open a corridor through to the open countryside beyond the trenches. Their heaviest blow would be aimed towards the British.

With the location selected, the Germans gathered their forces on the Western Front where they soon outnumbered the joint British-French armies by 191 division to 178. During the day on 20 March 1918, reports began to be received by British forces that German artillery was now in position to open fire.

A heavy fog had settled in the area and visibility fell to mere yards. At 4:40am on 21 March, the German artillery began to fire as Operation Michael began. It was one of the largest artillery bombardments in history and over 3 million shells were fired in just five hours. The town of Flesquieres was smothered in Mustard Gas and German artillery pounded British trenches and destroyed communications with areas behind the lines.

Five hours later German infantry advanced. The fog was so thick the British could not see them coming and, in some parts of the line, the artillery bombardment had been so ferocious that some British soldiers had been rendered virtually catatonic and were unable to function let alone defend their trenches.

With the front line being pierced in multiple places, some British soldiers reported threatening taunts being shouted through the fog by German soldiers who were surrounding them. In fear they turned and ran. The German army advanced throughout the day and continued to push as the British continued to retreat.

In Paris recriminations began between the different countries. The French blamed the British for retreating. The British blamed the French for a lack of support. Both blamed the Americans for not arriving in greater numbers. With huge German railway guns now able to fire at Paris, the French government began to discuss the possible need to evacuate the capital.

To stem the German attacks, the allies would need to agree a drastic solution.

Supreme Allied Command

Since the outbreak of war the British and French armies had been largely independent on the Western Front. Whilst they would coordinate with each other, and with the war being in France the French were nominally the senior partner, they could not issue orders to each other and retained their own commands.

However, the disaster unfolding on the Western Front forced the allies into finally appointing a single commander for all their forces. The man chosen was General Ferdinand Foch. Foch had commanded the French forces on the Somme in 1916 and played an important role in military plans between Britain and France before the outbreak of war.

With a single man now in command of the British, French, and American armies on the Western Front the allies could begin to come to grips with the German attacks.

Operation Michael came to an end on the 5th April. The Germans had made significant territorial gains but had found advancing over the ruins of the Somme battlefield difficult. More dramatically, whilst they had inflicted severe casualties on the British and French in the area, arriving Americans could eventually replace those losses. The thousands of German soldiers who had died could not be replaced.

Ludendorff launched another offensive near Lys in an attempt to capture nearby British railway routes that led to the channel ports. Again the Germans were able to force the allies back from the town of Armentieres and capturing the Messines Ridge.

However, like previously the Germans were still sustaining high casualties. More than this though, Ludendorff had shown a tendency to be distracted from his original objectives by the changing tactical situation. He would weaken his drive towards his main targets in an attempt to exploit new situations. When his attacks then lost momentum, the Germans had not made significant enough gains.

The Germans had hoped to capture the strategical important city of Amiens but the French in particular had held out in the area and blunted the German attacks.

As Ludendorff began to introduce new offensives, the initial impetus of the attacks was being lost. This presented a Foch with a real chance.

Turning the Tide

German forces had managed to push slowly but surely to within 90km of Paris but their manpower strength was beginning to ebb away. Rather than break through the allied lines, the Germans had created several notable ‘salients‘ or bulges in the line. Whilst allowing the Germans to move forward these salients were also vulnerable as they could be surrounded on three sides.

Ludendorff launched a penultimate attack near the River Matz to try and force a way through but the allies, who by now had strengthened their defenses and after the shock of 21 March were able to hold them at bay.

A final attack was then attempted by the Germans on 15 July near Champagne but failed to break the allied lines. Rather than let the Germans consolidate their positions this time though, Foch ordered an immediate allied counter attack on 18 July.

The German army had been exhausted by their efforts so far and were stunned by the sudden French attack which threatened to collapse the salient and trap thousands of German soldiers. Fearing a disaster Ludendorff ordered the immediate evacuation of the battlefront.

As the Germans withdrew the allies began to chase them.

Despite coming so close to breaking the British and French armies apart in March, Ludendorff had achieved nothing more than exhausting his own army and losing thousands of his best soldiers.

The allies had weathered the worst that the Germans had been able to offer and were emerging stronger than they had been before. With Foch in complete control of allied strategy, the British, French, and American armies could now act with unified purpose.

Furthermore the flood of American soldiers that the Germans had feared was now arriving. On 30 March there had been only 284,000 American soldiers in France. By 20 July there were over a million. At times 10,000 Americans were arriving in France on a single day. The allies were able to replace their losses. The Germans were not.

As the German army began to fall back their morale began to collapse.

The end of the war was suddenly in sight.