When thousands of British soldiers, including men from the Royal Sussex Regiment, died at Aubers Ridge in 1915, it began a scandal that reshaped the Government and wartime production.

The end of 1914 had failed to bring about the end of the First World War. The hoped for war of movement had failed to materialise. It had been replaced by the tactical and strategic stalemate of trenches. Whilst the British had launched an extensive recruitment drive at the outbreak of war, those men who had joined the army still needed to undergo training. This meant that the tiny British Expeditionary Force (B.E.F.) would continue to hold the line alongside the Belgian and French armies against the might of the German army.

The First Battle of Ypres had brought about heavy losses in the B.E.F. as both the Entente allies and the Germans sought ways to break the deadlock.

On the 22nd April 1915, the Germans utilised gas weaponry for the first time as they launched another offensive against British positions at the town of Ypres. The Second Battle of Ypres, which began that day, would last until the end of May.

Pressure needed to be alleviated from these front lines.

Second Battle of Artois

Whilst the German Army had begun to fight again at Ypres, their primary focus for 1915 was away to the Eastern Front fighting the Russians. If the Russian Army could be defeated in battle, then the Germans would be able to bring their forces away from that front and redeploy them against Britain and France. Such a numerical superiority would likely bring about the end of the war.

To make the most of the German’s distraction away to the east, the French commander-in-chief General Joseph Joffre decided to launch multiple offensives into German positions around Artois, Rheims, and Verdun. The planning for this attack began in March 1915, and it was agreed that the British would act in support of the French Army.

General Douglas Haig began planning for the attack from the end of April, just before the Entente nations launched their attack on Gallipoli. Ongoing German struggles in the east and the sinking of the Lusitania gave Britain and France a propaganda advantage over Germany and a sense of building momentum.

The original plan was for the French to attack first and, a day later, for the British to launch a subsidiary attack against German positions. It was decided that the British would launch their attack on Aubers Ridge near Vimy. The capture of the heights would provide security for the French attack and remove a dangerous German position from the British front.

The German attack on Ypres did not heavily disrupt these plans, but poor weather meant that the attack was rescheduled first to the 7th May and then again to the 9th. However, Joffre also adapted his plans. Now the British and the French would attack at the same time, rather than the British a day later. Whereas the British had intended to attack positions that might have been stripped of defenders to deal with the attacking French, they would now lose this potential advantage.

Aubers Ridge

View of the Battle of Aubers Ridge, attack on Fromelles. During the bombardment 9th May 1915. Smoke is rising from the German lines. – Image Courtesy of the Imperial War Museum (IWM Q 51624)

The ground where the British were scheduled to attack was not ideal for combat. The land was largely flat, with little cover, and was also criss-crossed by numerous ditches and drainage streams. Whilst some could be navigated or hurdled, others could be fifteen feet wide. The German lines lay between 100 and 500 yards from the British, and several sections of the enemy trenches could not be seen from the British position. Furthermore the German’s had been systematically strengthening their defenses in the area.

Newly installed and upgraded breastworks were now thicker and wider making it far more difficult to scale or traverse them in an attack. Machine guns had been installed just above ground level with clear fields of fire. Destroying such defenses would be difficult even if the British knew about them. But intelligence on the German positions was sketchy in places.

Furthermore, the British Army in the area was also heavily hampered by an ongoing shortage of artillery pieces and ammunition. Production on the home front had consistently failed to keep up with demand. Some of the artillery guns the British were forced to employ were effectively obsolete. As would shortly be discovered, a number of the shells to be used were faulty and would either never explode, or instead would detonate within the gun itself.

Whilst those planning the attack were unsure if the German’s knew the assault was coming, some in the trenches were much more certain. German soldiers in the opposite trenches had taken to shouting that they knew an attack was imminent.

At 5am on 9th May, the British guns began shelling the German line with shrapnel shells. These weapons were believed to be best suited to cut or destroy barbed wire defences. This was a school of thought which would be replicated during the preliminary bombardment at the Battle of the Somme. At 5:30am the British guns changed to high explosive shells aimed at the German trenches and breastworks in an attempt to destroy these positions and open a route inside for British soldiers.

Shortly afterwards the first wave of British soldiers went over the top. Among them were the 2nd battalion of the Royal Sussex Regiment. As these soldiers left their trenches they were immediately greeted with sustained German fire. The new machine gun positions recently installed by the Germans ensured that fire was directed at attackers’ knee height to ensure it could not be avoided. German artillery, which had been largely undisturbed by the British shelling could also now open fire onto No Man’s Land.

From around 850 men of the battalion, 565 became casualties with at least 260 of them being killed.

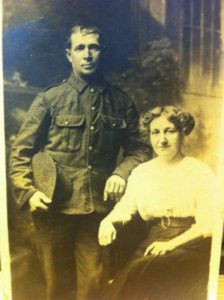

Among them was Moses David Sands. Sands was born on 26th April 1874 to George and Margaret Sands of St Leonard’s-on-Sea. By the age of eight he had moved with his family to Eastbourne. On 12 August 1893, Moses married Esther Elizabeth Erridge in Eastbourne. They had nine children between 1894 and 1909. Moses signed up to the join the Royal Sussex regiment at the outbreak of war in 1914. Shortly after he ventured over the top on 9 May he was killed by a shell.

As the day progressed, British attacks became bogged down by stiff German defences and barbed wire left intact. Many of those who were killed, died yards from their own trenches as they attempted to advance over the open ground. British commanders Haig and Major-General Gough attempted to force the position during the afternoon and into the night, but the German defences could not be breached.

By the morning of 10 May, the attack had stopped.

Aftermath

Over 11,000 British soldiers had become casualties during the attempt to take Aubers Ridge and the battle had been a disastrous failure.

In conversations and correspondence with the Times War Correspondent Charles à Court Repington, the commander of the B.E.F. General Sir John French, placed the blame squarely on the inability of British armament production to provide the army with tools to win the war. When Repington reported this back in Britain it caused what is latterly known as the ‘Shell Crisis,’ which ended up effectively toppling the government and saw private armament factories placed under the control of the newly created Minister for Munitions David Lloyd George.

General French would shortly be relieved of his command and replaced by Douglas Haig, as the military and governmental make up of Britain shifted in light of the war’s progress and the failure at Auber’s Ridge.

Back home some good would emerge from the destruction and death of the battle. Among the survivors of the Battle of Aubers Ridge was John William Tutt.

Tutt had been born in October 1881 in Eastbourne. He married Emily Mary Elizabeth Barnard on 11 June 1905. Whilst married and father to four children, Tutt joined the Royal Sussex Regiment. In March 1915 whilst John was serving in France, Emily passed away. When the Royal Sussex Regiment attacked at Aubers Ridge, Tutt saw his comrade Moses Sands die in action. In March of 1918, having come back from the war John met and married Esther Sands, Moses’ widow, combining the two families. John died in Dec 1961 aged 79 and three years after Esther.

This story includes information kindly supplied by John Staples, the Great-Grandson of Moses Sands.