Did you know that American soldiers first began arriving in France on 26th June 1917, to fight in the First World War?

Although the plot orchestrated earlier in the year by German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmerman to pit Mexico against America had spectacularly failed to keep the United States out of the conflict, America’s declaration of war in April 1917 did not immediately bring the American military into battle.

Initially it was not totally clear if American forces would be deployed overseas. Both Britain and France desired the introduction of additional reinforcements but were also interested in increased supplies from safe American factories.

However, for a burgeoning global power, America’s armed forces were almost non-existent. The most recent military endeavours the country had undertaken had been directed against Mexican bandits led by Pancho Villa, and now were potentially needed to participate in the greatest armed struggle in history.

Before the declaration of war, American generals had already begun work on a planned conscription law in the event of conflict. This new law was shortly enacted and became the Selective Service Act of 1917. It allowed the United States to quickly build an armed force in preparation for deployment abroad. Whilst the army’s tiny pre-war size was solved, it would still need to be prepared for battle.

American soldier undergoes bayonet training (United States Defense Visual Information Center via Wikimedia Commons)

Training the Army

In order to bring the newly expanded American army up to a fighting standard, the British and French dispatched a number of officers to America to provide training.

These British and French officers began instructing the American army in the means and methods of fighting a modern industrial war. However, important national and cultural differences existed between how Britain and France viewed and fought the war. Some of these differences would be transmitted to the American recruits.

They did not yet know it, but the majority of American soldiers would end up using French artillery pieces and a mix of British and, eventually, American made rifles. However, they would be trained to use a mix of weapons that they would never actually encounter.

Additionally, the personal attitudes of the training instructors would also influence the training regime, with more than one British officer informing the Americans that they should never accept the surrender of German soldiers and should summarily execute them instead.

Many American soldiers found the training to be a strange and confusing experience. The warfare they were being trained for did not seem to correspond to their expectations, with too much emphasis being placed on trenches and not enough on open fighting. Additionally the concept of army discipline and learning ‘not to think for yourself’ was at odds with their individualism.

However, their transition from individuals to a fighting collective would help them form a new group identity. With the American Civil War still a relatively recent event, tensions between the men of the north and the south were still present. However, together the American soldiers would come to be known as the ‘Doughboys‘.

As training continued it became apparent that the majority of the American army would not be ready to serve until 1918. However, the first detachments were prepared and sent to Europe during June 1917.

The U.S. Signal Corps, the first 5,000 American soldiers to reach England march across historic Westminster Bridge in London (Associated Press)

Deployment to Europe

The journey from America to Europe was a fraught one. The German U-Boats that had played a part in bringing America into the conflict still patrolled the Atlantic and would be keen to prevent American soldiers ever reaching the continent.

The majority of American soldiers were carried across the ocean by British ships in a convoy system to combat the activities of submarines. Remarkably, despite a few scares, not a single transport carrying American soldiers was lost at sea during the war.

Onboard the British ships, American soldiers had to get used to British food and customs. This was not an easy transition and many American soldiers found themselves thoroughly miserable on the roughly two week journey to Britain.

Most ships arrived in Liverpool, though some went directly to France, and American soldiers began their journey down the length of Britain to ports along the south coast. As the war continued soldiers could end up spending anywhere between a few days and a few weeks in Britain. Lieutenant Edgar Taylor, an American pilot who arrived in Britain in January 1918, spent several weeks living on the Sussex coast and practicing his flying in the area.

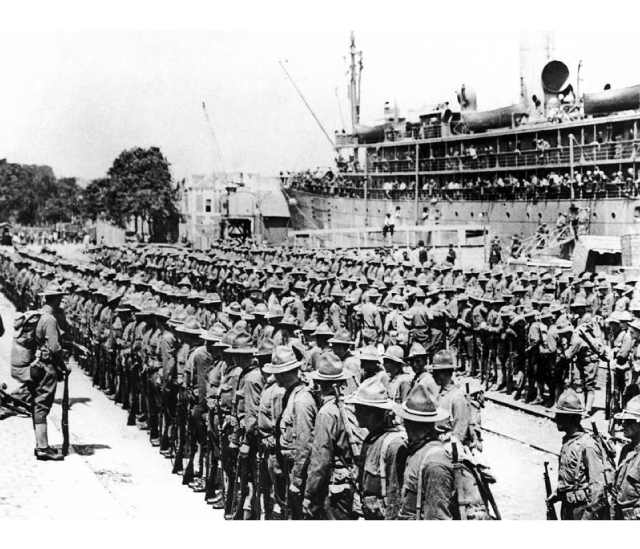

On 26th June 1917, the first 14,000 American soldiers began arriving at the port of St Nazaire in France. Their arrival had been kept a secret to further guard against German intervention, but it did not take long for the local French population to begin cheering them through the streets.

These soldiers were not yet destined for the front. The commander of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), General John Pershing, had already begun the organisation of further training camps for his men in France. Pershing himself had officially arrived in France on 13th June 1917.

There had been ongoing debates between Britain, France, and America over how best to utilise these new reinforcements. Both Britain and France wanted American troops to be amalgamated into their armies to replace men lost in battle. Pershing however was adamant that the American army would fight together as a cohesive unit, with a few notable and politically charged exceptions.

Pershing succeeded in his demands, but American soldiers spent a portion of their training time embedded with allied soldiers to learn in trenches. The majority of American soldiers ended up serving alongside French soldiers.

During the early negotiations and discussions between the allied armies, America and France had begun to bond over their shared revolutionary heritage, a state of affairs the British were not keen on.

Welcoming ceremonies were planned in Paris on 4th July 1917, American Independence Day. During one of these ceremonies, Lieutenant Colonel Charles Stanton visited the tomb of the Marquis de La Fayette; a hero of the American War of Independence.

There he gave a speech that was later misattributed to Pershing:

‘America has joined forces with the Allied Powers, and what we have of blood and treasure are yours. Therefore it is that with loving pride we drape the colors in tribute of respect to this citizen of your great republic. And here and now, in the presence of the illustrious dead, we pledge our hearts and our honor in carrying this war to a successful issue. Lafayette, we are here.’

Swelling the ranks

The majority of American soldiers did not begin arriving in France until 1918.

Following the Russian Revolutions and their exit from the conflict, Germany was forced to make use of their temporary numerical superiority in March 1918 by launching their Spring Offensive designed to split the British and French armies apart and win the war before America could deploy overwhelming numbers.

By the end of March 1918 there were still only 284,000 American soldiers in France. However, the German offensive forced America to begin deploying soldiers quicker than had previously been intended. As the German attack began to bog down and lose its momentum, American reinforcements began to arrive en masse.

By July 1918 the AEF now numbered one million men. By November it had reached 1.8 million. During this period of the war around 10,000 American soldiers were arriving every day.

Faced with a deteriorating situation and becoming more outnumbered by the day, Germany was forced onto the retreat and eventually surrendered.

America finished the war having lost 53,402 men in combat. This was actually less than the 63,114 Americans who died of diseases, primarily the Influenza Pandemic that swept the world.

In real terms the AEF only spent around 200 days in actual combat during the war, but their arrival began the process of securing victory on the Western Front. The first 14,000 men to arrive were the opening trickle of an eventual flood that would threaten to wash away the German resistance in France and Belgium.