Whilst fighting continued on the front lines in 1918, a more serious and deadly threat was beginning to appear. It would claim the lives of millions worldwide and the people of East Sussex would not escape its effects.

1918 would see the end of the war in Europe and the eventual victory of France, Britain and America against the German army. However, the emergence of a highly infectious and deadly form of influenza also swept the world, over the course of 1918 and 1919. Exhausted by the fighting and rationing, the people of many countries found themselves already weakened before the virus struck and, as a result, had little ability to fend it off.

Origins

Whilst commonly referred to as the ‘Spanish Flu,’ the actual origin of the influenza strain that spread around the world in 1918 and 1919 is difficult to be certain of. Recent studies suggest it originally began in China and was transported across the world by Chinese Labourers heading for the Western Front in Europe. The ‘Spanish’ connection came from newspaper reporting of the outbreak. In order to avoid causing alarm either at home or on the front lines, newspapers in Britain, France, Germany and America all restricted stories of the epidemic in their own country. This led to a high proportion of stories examining the effect in Spain, particularly after King Alfonso XIII became severely ill with the virus.

It has also been speculated that a British military camp at Etaples, which was also the site of a mutiny in 1917, may have been the epicentre for the virus. The huge movement of men across the world because of the war meant that the virus was transmitted across oceans and continents infecting people as it went. The arrival of these men at key camps or transport hubs meant that the infection could then be spread in all directions by those who had come into contact with it.

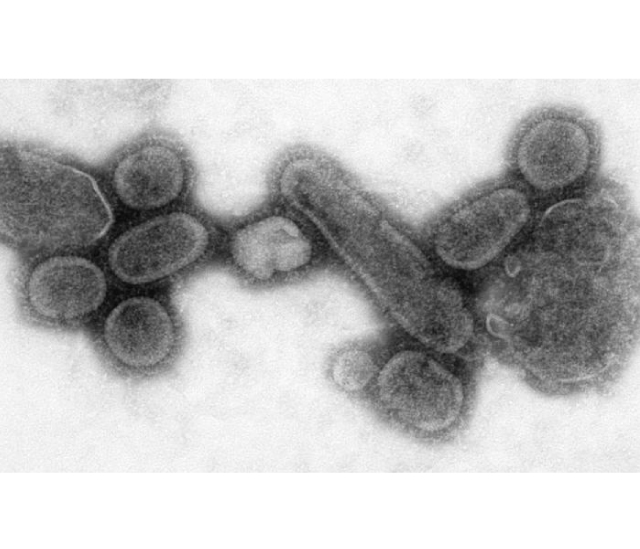

Symptoms and effects

The virus was notable for being both highly infectious and for also causing incredibly high fatalities in those who contracted it. The virus often caused extreme bleeding from particular mucous membranes such as the nose and the linings of stomach and intestine. Over half of the people who came into contact with the virus would become infected and this was not helped by the tendency of those suffering from it to have large, and obviously highly infectious, nosebleeds. Most of those who died from the virus were killed by pneumonia, which was a byproduct of the influenza, but many also died from blood loss and the virus itself. One of the virus’ most deadly tendencies was to invoke an overreaction of the suffer’s immune system, known as a cytokine storm, resulting in both the virus and the immune system attacking the body causing trhe patient’s death.

The epidemic had three major peaks around the world. The first of which bore all the resemblance to traditional influenza. It proved most dangerous to the young and those over 65. The second wave however saw the virus mutate into something far more deadly. This new virus was unusual in that it often targeted young adults rather than those who had contracted the first virus, many of these first wave survivors appeared to have developed a measure of resistance to it. Another group that was disproportionately affected, in comparison to other influenza outbreaks, were pregnant women.

The third and final wave of the virus was not as deadly as the previous mutation but still caused a disproportionate amount of deaths to tip the virus back into pandemic state.

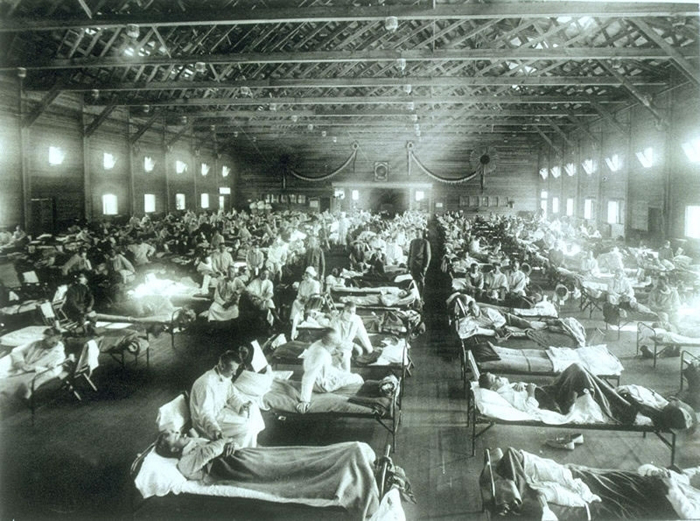

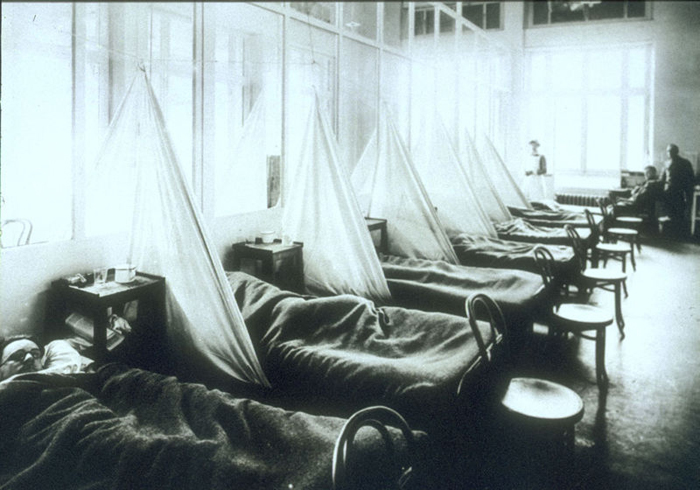

One of the key factors in the transmission of the virus lay with the treatment of those who were highly ill and infected in the army. Traditionally, speaking in civilian life those who were extremely ill remained stationary, usually at home, and were treated there. In the army, those who were in similar situations were, by necessity, evacuated from the trenches and passed through various field hospitals and medical outposts. Those men who were suffering from the virus brought it with them out of the trenches and into hospitals and railways stations. From there it spread.

Outbreak in East Sussex

The first wave of the virus arrived in East Sussex in the summer of 1918. Its exact point of arrival into the country is unclear but naval bases at Scapa Flow, Scotland, showed the first signs of infection in May and the virus arrived in Glasgow shortly afterwards. It then appears to have travelled down the country to the East Sussex coast. 1918 was to be the decisive year of the war. Following the German attack in March, the fighting in France and Belgium had been fierce and constant. As a result, not many members of the public were properly paying attention to the virus in their midst. In his study into the outbreak in East Sussex, Jaime Kaminski shows that the press and some local department stores of Brighton were incredibly light-hearted about the outbreak. The shop Hanningtons took out an advert in the Brighton Gazette declaring a new ‘Sales’ to be the best method of treating the sickness.

This did not last when, in October and November 1918, the virus mutated and entered its far more deadly second wave. By the week ending 19 October, 16 people from East Sussex, including Brighton and Hove, had died in the new outbreak. This increased to 55 the following week and 92 the week after that. The epidemic peaked the week ending 9 November with 101 fatalities. It would begin to steadily decrease after this period but, by the end of January, over 600 lives had been lost in the county. At the height of the epidemic primary schools were closed, though secondary schools remained open. Of particular concern to local authorities was the risk of infection on public transport or in entertainment venues such as cinemas or music halls. In response to the virus, many people began walking to work rather than risk using trams or buses whilst Local Government Boards brought in regulations that restricted entertainment venues from operating for more than three consecutive hours. Despite this, there was little interest in disinfecting the halls after each show.

The additional danger of the epidemic was the likelihood of medical staff contracting it and spreading it to other patients before succumbing themselves. At Brighton Infirmary, of 141 influenza patients being treated 12 were their own nurses. Of 14 Queen’s Nurses at the hospital on Elm Grove, 8 had contracted the virus and were severely afflicted with pneumonia. Upon contracting the virus whilst in East Sussex, the poet Robert Graves claimed that there was not a nurse to be found anywhere in Brighton as the medical services were stretched to breaking point.

The third wave of the virus would then follow in January and February 1919. It was not as deadly as the previous wave but by the end of March it had still accounted for 157 additional fatalities in East Sussex.

Aftermath

The exact death toll from the virus is unknown but the figure in Britain is usually stated to be around 250,000. In total, the war killed over 704,000 men from the British Isles. In France, 400,000 people died from the flu and over half a million in the United States. The death toll in India has been estimated as between 10 and 17 million dead. It is estimated that a third of the world’s population was infected and between 10 and 20% of those who were infected died. Estimates for the total death toll caused by the influenza outbreak range from 25 to 100 million people.

Sources

A terrible toll of life: The impact of the ‘Spanish Influenza’ epidemic on Brighton 1918-19 – Jaime Kaminski