The destructive power of the weaponry used during the First World War dramatically changed the nature of military medicine. The wounds some men sustained tested the expertise of doctors to the limit and new innovations were required to deal with the wounds of war. East Sussex played host to hospitals and doctors who battled to rebuild their patients.

The manner and location of the fighting during First World War on the Western Front was greatly removed from the environment that the British Army was accustomed to operating in. Conflicts across the Empire, such as the Boer War, had meant very particular forms of battlefield medicine. The change from African battlefields to those in the fields and countryside of France and Belgium was to initially prove a tough obstacle for the Army Medical Corps to overcome.

The Western Front

The large scale use of weaponry, such as machine guns and artillery, coupled with the deployment of armies into the trenches meant that, if suffered, wounds could be incredibly serious. Artillery shells could easily remove men’s limbs or inflict terrible damage upon their bodies. Machine gun bullets could fracture bones and pierce organs. The muddy and watery conditions of the Western Front, large portions of which had been well-tended and manured farmland before the war, were also ripe for infection.

As historian Joanna Bourke explains, the war produced wounded men in staggering numbers:

In France there were 5 casualties for every 9 men sent out, compared with 2 for every 9 in the Dardanelles and only 1 to every 12 in Salonica and East Africa. Furthermore 31 per cent of those who served in the army were wounded, compared with only 3 or 4 per cent of those in the navy or airforce. In the first year of the war, 24 per cent of officers and 17 per cent of soldiers in Other Ranks were wounded. Between October 1915 and September 1918, 12 to 17 per cent of soldiers of Other Ranks were wounded each year.

The severity of these mutilations was unprecedented … All parts of the body were at risk: head, shoulder, arm, chest, intestines, buttock, penis, leg, foot. Over 41,000 men had their limbs amputated during the war – of these 69 per cent lost one leg, 28 per cent lost one arm, and nearly 3 per cent lost both legs or arms. Another two hundred and seventy two thousand suffered injuries in the arms or legs that did not require amputation. Sixty thousand, five hundred were wounded in the head or eyes. Eighty-nine thousand sustained other serious damage to their bodies.

During large scale operations, field hospitals would often become overwhelmed with casualties. In the initial years of the war, before its conditions were fully understood, infection could fester in men who could otherwise have been successfully treated and saved and led to loss of limbs and lives. Army medicine was undergoing a steep learning curve and many techniques would have to be re-written or invented to deal with the numbers of wounded men.

Treatment

The initial, and obvious, aim of treating men wounded in the First World War was to save their lives and as much of their bodies as possible. The first stage of this process lay with the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). The RAMC composed of doctors, stretcher bearers and ambulance drivers were often the first to begin structured treatment of soldiers who had been wounded. There were also large numbers of female nurses operating within field hospitals in the various theatres of the war, as well as in the established hospitals on the home front. Many of these women were members of the the Volunteer Aid Detachment (VAD). The VADs fell under the control and administration of the War Office during the conflict and it is from them they drew their pay. Some VADs who were abroad in one of the British Red Cross Hospitals or those run by the St John’s Ambulance drew their payment from the Red Cross. The conditions at the front were not conducive to swift medical treatment.

The conditions on the front line meant a lower standard of medical care, unhygienic equipment, lack of water, inadequate lighting and poor supplies of operating instruments, including ligatures, needles and supports. When this is considered against the remarkable fact that it took, on average, between eight and twelve hours to evacuate a wounded soldier from the front to a Casualty Clearing Station (CCS), it is not surprising that so many men returned home without a limb. The even starker situation at Gallipoli, where a soldier had to face a voyage of two to three days, led Major Stanley Argyle to despair at the number of limbs that were amputated and lives lost that would otherwise have been saved. – William Birnie

However, whilst the treatment of wounded men was a priority, the objectives of this treatment could fall into two different lines depending on the wound. Were wounded soldiers being treated so they could recover from their wounds and go on to lead as happy and normal a life as possible, or were they being treated so they could recover their strength and return to the war? Some wounds would, of course, prevent the man from returning to action. But this split objective manifested itself most obviously in the treatment of shell shock. Medical professionals such as William H Rivers and Lewis R Yealland had conflicting approaches to the treatment of shell shock or ‘war neuroses’. Rivers preferred a form of counselling whilst Yealland favoured a more regimented system of punishments, autosuggestion and, if required, electric shocks. The use of electric shocks to stimulate recovery of muscles and limbs was also pioneered by the women of the Almeric Paget Military Massage Corps.

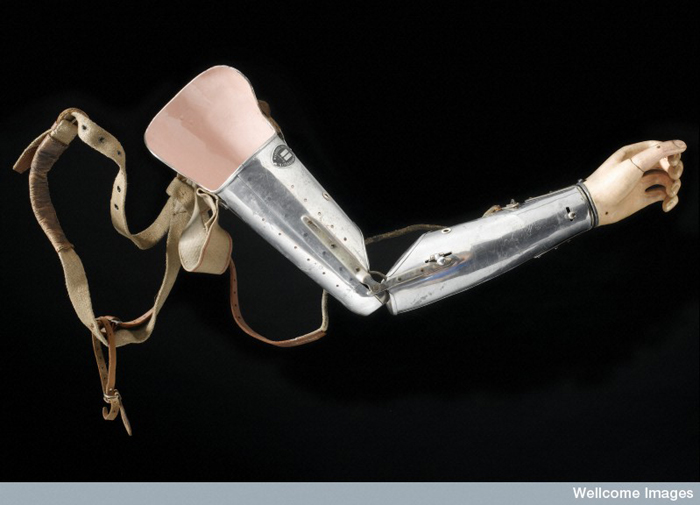

For men who had lost arms or legs, their immediate future was difficult to say the least. Before the First World War, prosthetic arms and legs were incredibly heavy and unwieldy designs that often cause the wearer a great deal of pain and discomfort. Over time they would degrade and break and they were expensive to acquire or repair. They also paid very little regard to functionality and, as a result, were – particularly in the case of arms – almost useless as usable replacements. Additionally, whilst servicemen were permitted to receive free artificial limbs (before the war they had only ever been free to those who had lost limbs in military service), the demand for them completely outstripped supply. The huge numbers of men who lost limbs in the war prompted a revolution in the treatment of amputees and the design of prosthetic arms and legs.

Two American firms, Rowley and Hanger, were invited by the government to set up subsidiaries in Roehampton, London, in the grounds of a former mansion commandeered by the Imperial War Office. This site became Queen Mary’s Hospital and opened its doors to its first 25 patients in 1915. During the war it became known as one of the world’s leading limb fitting and amputee rehabilitation centres, providing treatment and training opportunities so that patients could later find employment. Demand was high and often men left hospital with artificial arms without the proper training in their use. Artificial limbs were made on-site, yet, despite this, limb provision remained a struggle and it was only after the armistice that the situation was brought under control. New mechanisms were patented and lucrative government contracts enabled new research and developments to take place. – William Birnie

Prosthetic arms, such as the one on the right, were designed during the war to overcome some of the deficiencies of older designs. These include new features such as;

Made from aluminium, this prosthetic left arm has a canvas coated hand to give the appearance of a gloved hand. The fingers of the hand are set in position. The joints of the arm are adjustable and the hand is removable. Aluminium was preferred to wood as it was much lighter and was more comfortable for the wearer. As such it is one of a new generation of metal limbs that appeared in the 1920s and which gradually replaced the predominantly wooden ones. The arm is strapped to the shoulder with padding. The McKay Prosthetic Limb Company who made this arm was one of a number of companies set up during and immediately after the First World War. They were seeking lucrative government contracts to supply soldiers who had lost limbs in the conflict. – Europeana

Whilst it is more commonly know as a hospital for the treatment of Indian soldiers during the war, the Royal Pavilion at Brighton also served as a hospital for ‘limbless soldiers’. The local magazine the ‘Brighton Season’ covered the activities of the hospital in its 1917-1918 edition.

- Brighton Season 1917-1918. Courtesy of The Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton & Hove

- Brighton Season 1917-1918. Courtesy of The Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton & Hove

- Brighton Season 1917-1918. Courtesy of The Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton & Hove

Once the lives of the men were saved, the focus moved on to providing them with the skills and trades to support themselves in civilian life. The men who had gone to war were, generally speaking, the backbone of the country’s working classes and productivity. It was important for the country’s economy for such men to contribute again after being medically discharged. A Queen Mary’s Workshop was opened in the grounds of the Pavilion and, inside, men were taught new skills and new trades such as cobbling and engineering in order to find civilian jobs. Whilst staying at the hospital some soldiers got involved with producing the hospital newspaper ‘Pavilion Blues‘.

Other men were sent to establishments such as Chailey Heritage School where they would undergo ‘educative convalescence‘ and learn how to overcome their injuries from children who were also missing limbs or had other physical impediments.

Following their treatment in hospitals like the Pavilion and also once they had undergone a period of retraining, wounded men would be sent to Roehampton for fitting of their final prosthetic limb. New jobs and industries began to open in Brighton and East Sussex to provide careers for these wounded men. The diamond merchant Bernard Oppenheimer opened a diamond polishing factory in Brighton and recruited heavily from the population of wounded soldiers.

The end of the war would not bring about the end of the difficulties for the men who had been wounded in it. In an attempt to write them out of wartime experience, no wounded men were part of the victory parades through London in the aftermath of the armistice and the peace. Additionally, whilst wounded men were entitled to a war pension, the amount they received was commensurate with the level of their wound.

The loss of two or more limbs, for example, entitled a man to a 100% pension, whereas amputation of a leg above the knee was assessed at 60% and below the knee at 50%. Psychological and functional somatic disorders, such as shell-shock, were more difficult to categorise – Edgar Jones et al

A pension would be paid to the widows of those men who were killed in the war or died of their wounds but, again, the exact amount was often influenced by various factors such as the man’s rank, his wife’s occupation (if any) and the number of children (either legitimate or illegitimate) that they may have had.

In the years after the war, men who had obvious war wounds found themselves shunned by a society that no longer wished for visual reminders of the conflict. The lack of any substantive welfare system meant that many men found themselves in increasingly dire financial and medical situations. Whilst some care homes and facilities continued to operate in the post war years many stopped or closed shortly after the conflict. The implication being that their war work was now completed.

But, for a time, many of the men who had suffered such horrific wounds found treatment and solace in East Sussex. The view and treatment of disabled people changed dramatically during the war and in its aftermath. The treatments and techniques required to save the lives of those wounded on the battlefield, had a huge impact on modern understandings of medicine. The fields of prosthetics, skin-grafting, and psychiatry and counselling, were revolutionised by the First World War. The medical profession would never be the same again.

Sources

Julie Anderson – Wounding in the First World War

William Birnie – Object of the month: First World War amputees

Joanna Bourke – Dismembering the Male

Edgar Jones et al – War Pensions

Scarletfinders.co.uk – British Military Nurses

This story was written with support from The Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton & Hove