Whilst battle raged on land during the First World War, the seas and oceans became new battlefields. Danger lurked beneath the waves and East Sussex found itself on the frontline.

By the time 1914 had become 1915, it was clear to most of the combatants on the Western Front that the war would not be won as quickly as some had hoped. With all sides still trying to exert military dominance in the trenches, both Britain and Germany had begun to look beyond the land war and out to sea for a possible solution.

Britain had been using the Royal Navy to blockade Germany since the outbreak of the war and by November 1914 had termed the seas around Germany to be a War Zone with any ships entering it doing so at their own risk. This blockade of Germany prevented most forms of trade and material, including food, from entering their ports.

U-Boat Warfare

In retaliation the Germans turned not to their surface navy but instead to their U-Boat fleet, U-Boat being the abbreviation of Unterseeboot; literally undersea boat, to prevent shipping from reaching the British Isles. They too declared the waters around their enemy to be a War Zone, although given the sheer amount of trade Britain conducted with the rest of the world, there were grave concerns within Germany that the indiscriminate sinking of foreign vessels may anger neutral parties such as the United States.

German U-Boats had already sunk several civilian and relief ships when, on 7 May 1915, the liner RMS Lusitania was torpedoed off the coast of Ireland. It sank in under twenty minutes and only 761 of the 1,959 people on board survived. Among the dead were 128 American civilians.

The sinking of the Lusitania remains a topic of high contention. At the time, Germany maintained that, as the ship carried military supplies and ammunition destined for the Western Front, it could not truly be considered a neutral target. The German embassy had also placed adverts in major American newspapers outlining the current War Zone around Britain and warning travellers of the risks in sailing.

For their part, the British and Americans viewed the sinking as little short of a war crime. The Lusitania had been flying no flag at the time of her sinking and was a recognisably large steam liner which carried no weaponry.

In order to prevent American anger from dragging them into the war, the Germans curtailed their U-Boat activities. However by 1916, the lack of breakthrough on the Western Front and the intensifying combat at Verdun meant the Germans once again instituted a policy of unrestricted U-Boat warfare against armed merchant ships. At the time, passenger ships were not permitted as targets, in an attempt to once again avoid the wrath of the United States.

The SS Sussex

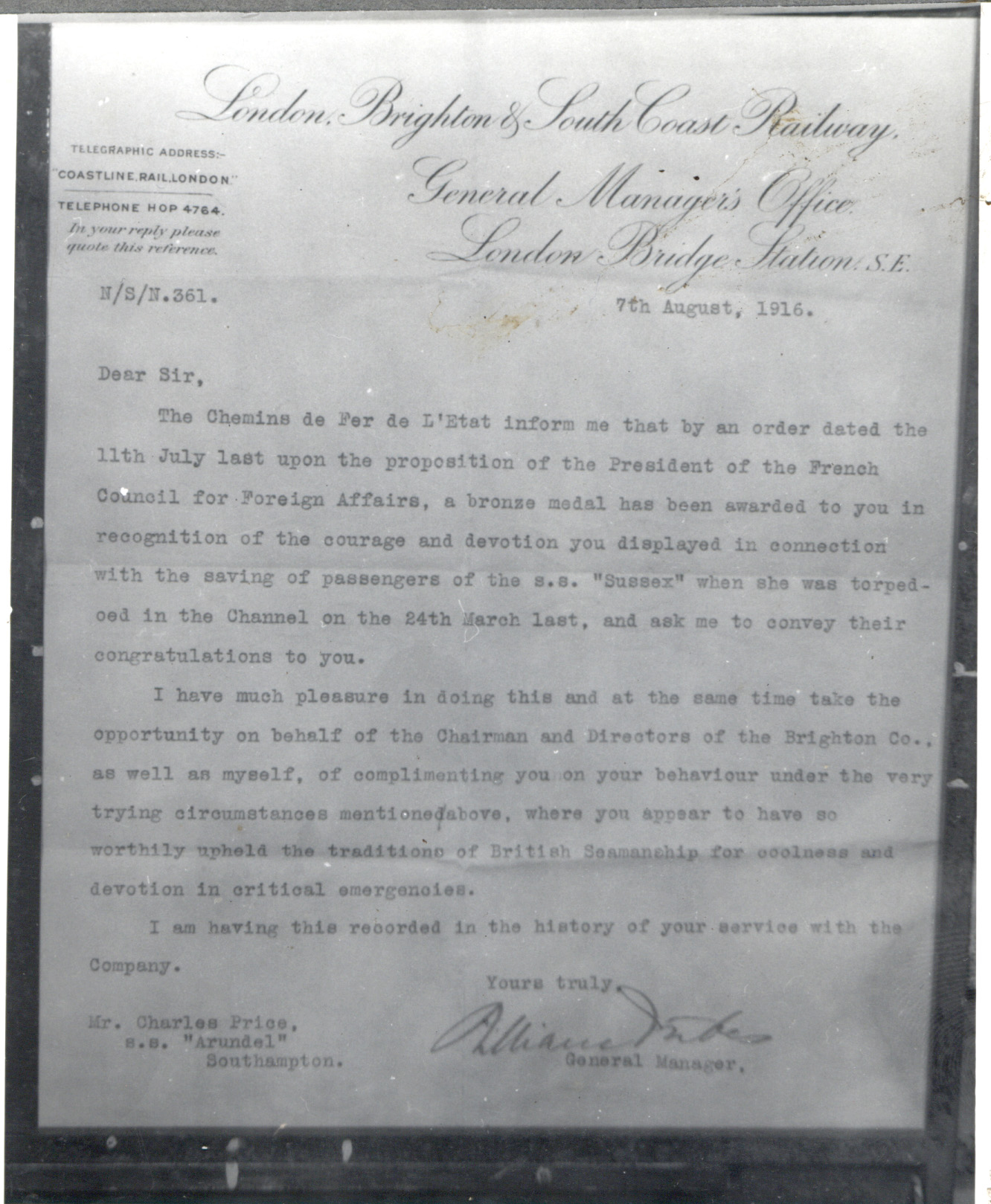

A letter of commendation to Charles Price, a local resident, for his actions following the attack on the SS Sussex. Courtesy of Newhaven Museum

This policy was unsuccessful. With Newhaven being used as the primary port for all military supply to France, cross-channel passenger services had been relocated to Dover and Folkestone. On 24 March 1916 a German U-Boat torpedoed the passenger ferry SS Sussex.

Whilst the ship did not sink, it did suffer heavy damage and lost most of the bow. Casualty estimates varied but place the number killed at around 50. Several local residents of Newhaven who were first on the scene to rescue passengers from the channel were later awarded medals and commendations for their bravery.

Under further pressure from America, the Germans gave the ‘Sussex Pledge’ which guaranteed that passenger ships would not be sunk, merchant ships would not be sunk without confirmation of weaponry onboard, and that provision would be made for the rescue of the crew of any torpedoed ship.

Whilst this pledge once again kept America out of the war, it was revoked by Germany again in 1917 in the belief that they could score a decisive victory in the North Atlantic. They failed in this goal and served only to antagonise America to the point where the United States entered the war in April 1917.

U-118

Commissioned in May 1918, U-118 was a mine-laying German submarine. The vessel is credited with the torpedoing on two British ships during it’s service. However the end of the war in November 1918, and the terms of the armistice, saw it sail to France to be placed in the hands of the victorious allies.

In 1919, with the German Imperial Navy in the hands of Britain and France, the decision was made to commence the scrapping of numerous ships and submarines. On 15 April 1919, U-118 was being towed through the English Channel en route to the naval base at Scapa Flow. However, a storm broke the chains and the ship was cast adrift.

The residents of Hastings awoke the next moment to find a new feature on the beach directly opposite the Queens Hotel. The beached U-Boat rapidly became a tourist attraction attracting hundreds of visitors to the beach.

For the first two weeks after it was stranded, the Admiralty allowed people to pay sixpence to go onto the deck of the submarine, thereby raising £300 for the Mayor’s Welcome Home Fund for returning soldiers. Two members of the local coastguard, chief boatman William Heard and chief officer W. Moore, gave tours of the inside of the ship for important visitors.

However, by the end of April both men began complaining of severe internal pains and the tours were suspended. Initially, it was thought that the stench of rotting food was the culprit but the men’s condition deteriorated rapidly. Moore died in December 1919, and Heard followed him in February 1920. A later inquest reported that both men had developed large abscesses in their lungs and brain, suggesting that chlorine gas had leaked from the ships batteries and poisoned them.

Eventually the ship became less of a tourist attraction and more of a nuisance that needed to be dealt with. Its proximity to the street meant it could not be detonated by explosive. Several tractors attempted to refloat it and a French naval ship tried to break it up by directing fire from its guns, but none were successful.

Between October and December 1919, the decision was made to break the ship up on the beach. The main naval gun was donated to the town of Hastings but was partially buried in 1921. It was later recovered but despite calls for it to be mounted on a plinth in the town, it too was broken down and dispersed.

Sources