During the First World War, Nelson Victor Carter exhibited tremendous bravery and heroism on ‘The Day that Sussex Died’

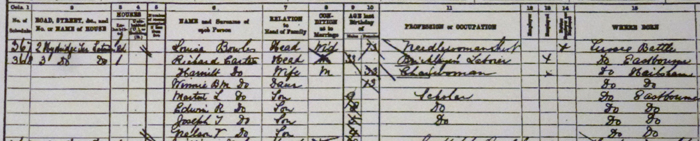

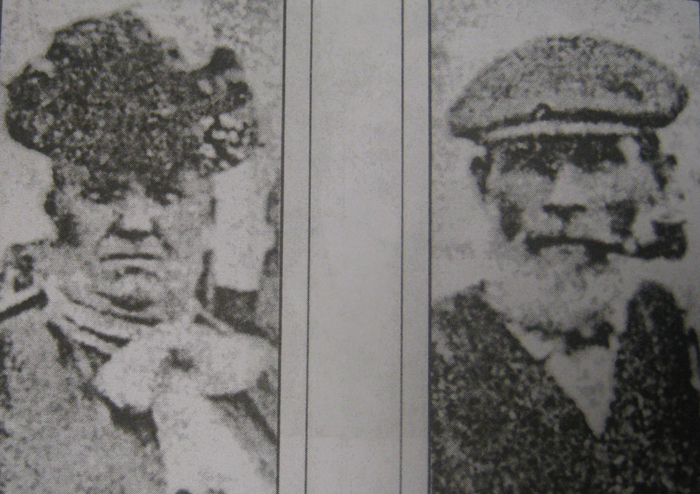

Nelson Victor Carter was born at 3 Hydridge Terrace, Latimer Road, Eastbourne, on 6 April 1887, one of nine children born to Richard and Harriet Carter (1). His father was a fisherman and his mother, a charwoman (2).

When Nelson was six, the family moved to nearby Hailsham and lived in a small worker’s cottage on what was then Brewery Road, now Battle Road. The house was described as “a typical rural labourer’s cottage, lacking perhaps, outward evidence of recent renovations but delightfully and healthfully situated. You see it as you reach the brow of the hill. To the right are the silver sails of the Harebeating Windmill, a prominent landmark, and just beyond, through and over the hedges, are the white patches of the cottages, round which the village’s future V.C. was want to play as a child.” Richard Carter found work in the town as a bricklayer’s labourer (3).

On 30 April 1894 Nelson and two of his brothers, Joseph and Edward, enrolled at the Hailsham Board School, now Hailsham Community College (4). The school had opened in 1878 and the first Headteacher, Mr. Towler, was still in charge during Nelson’s time there. “[Nelson] was always a good lad and was liked by both teachers and schoolfellows,” Mr Towler remembered. “He was a keen lad and learned very quickly. He secured his ‘leaving certificate’ at twelve years of age, which shows him to have been a fairly good scholar.” A visiting inspector, noticing Nelson, was heard to predict, “That boy… will make a fine soldier presently.” (5)

Nelson left school on 2 February 1900 and went to work for Charles Goldsmith, a local haulier, before becoming a carter boy on the farm of a Mr. Simmonds (6). However farm work was not to his liking and he frequently voiced his discontent. At the age of fifteen, and with his two eldest brothers already in uniform, Nelson ran away to join the Army. “It was six weeks before we knew where he was,” said Mrs Carter. “He had joined the RFA [Royal Field Artillery] and had enlisted under a false name [‘Nelson Smith’] because he thought if I found him I would claim him out as being under age” (7).

Nelson served with the 53rd Brigade of the Royal Field Artillery, service number 28771, from 16 December 1902. He was promoted to acting Bombardier on 5 February 1903 but was forced to leave the RFA due to a diagnosis of ‘hammer toe’. Nelson was discharged from the Army as medically unfit on 17 August 1903 (8).

Nelson returned to Hailsham and work on the farm but all who knew him realised it would not be long before he was back in the Army. In 1906, Nelson enlisted with the Royal Garrison Artillery, the chosen regiment of his older brother, Edwin, and was posted to Dover on 14 September with the service number 25672. He was transferred to the 27th Brigade, then to the 22nd Brigade and finally posted to Singapore with the 78th Brigade.

It was here that his health failed again and Nelson was forced to return home for a series of operations on a hernia. He was medically discharged for the second time on 15 June 1909 (9). “He underwent several operations,” his mother remembered later, “and I would never believe that they would take him back in the Army again” (10). For the time being she was right; Nelson’s attempts to rejoin the Army failed and his plans to join the police force were equally thwarted due to his recent operations (11). Nelson moved into the Soldier’s and Sailor’s Home on Upperton Road, Eastbourne, to “regain his health and strength”, working locally as a groom (12).

It was while living at the Home that Nelson met Kathleen Camfield, whom he married on 13 October 1911 at St Mary’s Church, Old Town, Eastbourne (13). The following February, a son was born at their Broomfield Street address and they named him Richard but tragedy struck when Richard died just two months later (14).

Life continued and Kathleen, or Kitty as he called her, remembered how Nelson “obtained work at various places in the town – at Eversley Court, Endcliffe School and the Burlington Hotel. Lastly, he went to the Old Town Cinema as door attendant, and he was there nine months” (15).

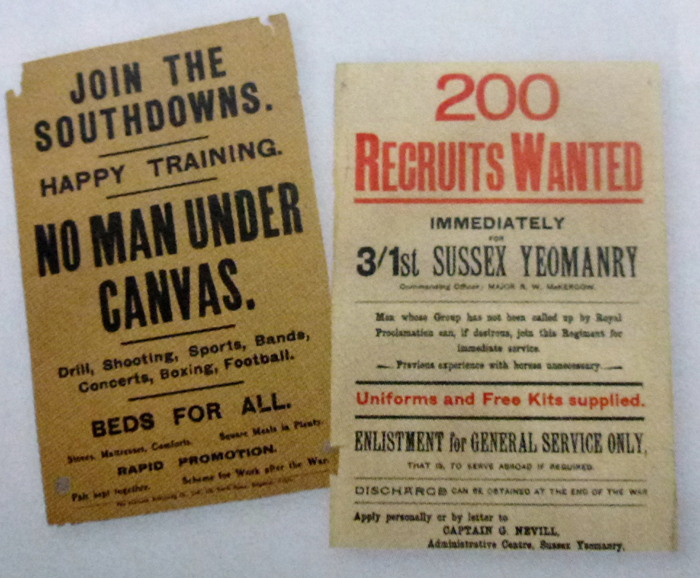

On 4 August 1914, Britain declared war on Germany and, a week later, Lord Kitchener announced his famous Call to Arms. The call was answered locally by Claude Lowther, veteran of the Boer War and then owner of Herstmonceux Castle. Lowther set about recruiting local men to his brand new Battalion and so successful was his campaign, and so willing were the Sussex volunteers, that by the following year Lowther had raised not one but three Southdown Battalions (16).

Nelson had been one of the first to sign up, joining the 1st Southdowns Battalion and receiving the service number SD4. Due to his previous experience, he was promoted to Corporal on the same day and sent to take part in training at Cooden Camp. On 29 September 1914, Nelson was promoted to Sergeant and to Colour Sergeant on 10 November, 1914. The following day, he was transferred to the 2nd Southdowns Battalion and on 28 January, 1915, was promoted to Company Sergeant Major, Warrant Officer Class 2, which led to a temporary Regimental Sergeant Major role from 20 August to 16 October 1915 (17).

A move to Detling in May 1915 coincided with all three Southdowns Battalions being inaugurated into the British Army as the 11th, 12th and 13th Battalions, Royal Sussex Regiment. Together with the 14th Hampshire Regiment, they made up the 116th Brigade of the 39th Division.

While the training continued, Nelson proved himself to be a keen sportsman. He stood just over six feet tall and, in 1915, became the heavyweight boxing champion of his Regiment, the 12th Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment, winning a silver cup, a medal and £5 (18). A letter, written to Kitty on 28 June 1916, suggests this was a pastime Nelson enjoyed before the War. “Has Charlie Collis joined up yet,” he asked. “You might tell him that I am alright but would like a good set too [sic] with the Gloves to keep me warm sometimes. fancy being under Canvass [sic] this weather its enough to freeze the knockers off the Doors.” Nelson also appears to have spent his time coaching the football team and would send cards home to his family and friends showing images from his latest theatrical performance (19).

- Nelson, standing far right, with the football team.

- No 1 Platoon at Bexhill, 1915. Nelson is seated, second row in the centre.

When the three Southdowns Battalions departed for France on 4 March 1916, Nelson left behind his wife, Kitty, and their infant daughter, Jessie, who had been born on 2 January (20). They arrived in Le Havre the following day to find snow on the ground and spent the next three months alternating their time between training, marching and shifts in the trenches. At the beginning of June 1916, Nelson was recommended for the Military Cross after carrying a wounded comrade four hundred yards to safety under heavy enemy fire (21). It was a sign of things to come.

The Battle of Boar’s Head was fought in the early hours of 30 June 1916 and although the soldiers who fought there didn’t know it, the battle was meant to be a diversion – so the Germans wouldn’t know where the main attack would come later. It was hoped that the enemy would move their troops to meet the threat, leaving the intended target, some fifty kilometers to the south, easy pickings in the days to come.

That main attack would become known as the Battle of the Somme.

The attack on the German outpost at Boar’s Head involved the 11th, 12th and 13th (Southdowns) Battalions of the Royal Sussex Regiment. The first bombardment, including wire-cutting by the artillery, had started on the afternoon of 29 June. The final bombardment began shortly before 3:00 a.m. when men of the 12th and 13th Battalions went over the top, most for the first time. The 11th Battalion played a supporting role after their commanding officer, grieving the loss of his brother, thought his inexperienced men would suffer disaster if they attempted the attack. If his men got to hear of his thoughts, they would understandably become nervous and so their role for the day was swapped with the 13th Battalion.

Captain G. D. Martineau recorded what he witnessed that morning –

[The 12th and 13th] seized the front line, which they held for four hours against considerably superior German forces, and even broke through to the support line, which they held for half an hour.

Naturally, it could not last. The Germans were ready. There is even a story that one man brought back a notice in English, announcing: “Come on, Sussex boys. We’ve been waiting for you for three days!”

A heavy barrage on the front line and communication trenches prevented reinforcements from being sent forward, the supply of bombs and ammunition gave out, and the valiant survivors were compelled to withdraw.

In fewer than five hours the three Southdowns Battalions of the Royal Sussex Regiment lost 17 officers, 76 non-commissioned officers and 349 men, including twelve sets of brothers, three from one family. A further 1000 men had been wounded or taken prisoner. Locals know it as the ‘Day Sussex Died’ (22).

Nelson’s actions that day were recorded by Lieutenant H. C. T. Robinson –

On the 30th of June, [Nelson] was in command of the last platoon to go over the parapet. When I last saw him he was close to the German line, acting as a leader of a small party of four or five men. I was afterwards told that he had entered the German second line and had brought back an enemy machine gun, having put the gun team out of action. I heard that he shot one of them with his revolver.

I next saw him about an hour later (I had been wounded in the meantime and was lying in our trench). [Nelson] repeatedly went over the parapet – I saw him going over alone – and carried in our wounded men from “No Man’s Land”. He brought them in on his back, and he could not have done this had he not possessed exceptional physical strength as well as courage.

It was in going over the sixth or seventh time that he was shot through the chest. I saw him fall just outside the trench. Somebody told me that he got back just inside our trench but I do not know for certain (23).

Nelson died within a few minutes and, like so many others who perished that day, was buried close to where he fell.

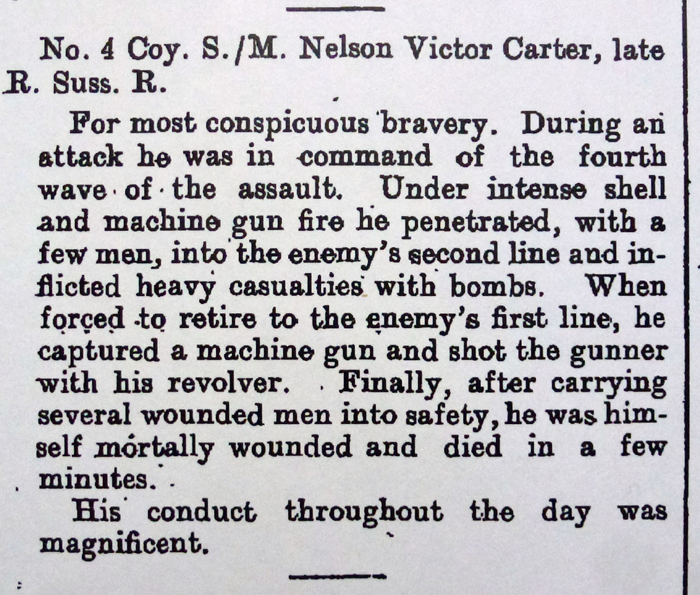

The London Gazette Supplement, dated 9 September 1916, announced that Nelson was to be awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions, the medal being passed to his widow, Kitty, from the hands of the King at a special ceremony at Buckingham Palace on 2 May 1917 (24). His citation read as follows –

In the early 1920s, Kitty received notification that Nelson’s body had been exhumed and moved to the Royal Irish Rifles Graveyard at Laventie, France (25). Today, Nelson is also remembered on both the Eastbourne and Hailsham War Memorials. His name appears on plaques at Hailsham Community College, at St Mary’s Church, Old Town, Eastbourne, and St Mary’s Church, Hailsham.

His home, and that of Kitty ad their daughter, Jessie, at 33 Grey’s Road is adorned with an historic marker in the form of a Blue Plaque, and the barracks on Seaside, Eastbourne, home of B Company (Royal Sussex), 3rd Battalion, Princess of Wales Royal Regiment, has been renamed Carter Barracks in his honour.

On 2 July 2016, Memorial Stones were unveiled in Eastbourne and Hailsham. Both towns, and their communities, will remember him.

Notes and Sources

1. Nelson’s birth certificate.

2. 1891 census.

3. Sussex County Herald, 16 September 1916; 1901 census.

4. Hailsham Community College Admission Register.

5. Sussex County Herald, 16 September 1916.

6. Ibid. 1901 census.

7. Sussex County Herald, 16 September 1916.

8. Victoria Cross Database, courtesy of Doug Arman.

9. Ibid; Nelson’s discharge papers, 1909.

10. Sussex County Herald, 16 September 1916.

11. Joseph Carter, a brother of Nelson’s great grandfather became Eastbourne’s first policeman in 1842. Constance June Bjorkquist, Carter Family History, published in Canada, 2012, pp 5-6.

12. Index to 1914-1918 War Memorial of Eastbourne, East Sussex, Transcribed and Published by PBN Publications, 1989; 1911 census.

13. Nelson and Kitty’s marriage certificate.

14. Richard’s birth certificate; correspondence with Margaret Smith and Doug Arman.

15. Sussex County Herald, 16 September 1916.

16. John A. Baines, The Day Sussex Died – A History of Lowther’s Lambs to the Boar’s Head Massacre, Firestep Books (revised edition), 2014, pp21-44.

17. Nelson’s Service History, National Archives.

18. Sussex County Herald, 16 September 1916.

19. Information provided by Geoffrey Baker, Nelson’s grandson.

20. Nelson’s Service History, National Archives.

21. Letter from Captain Harold Robinson to Kitty, 11 September 1916.

22. Royalsussex.org.uk/Richebourg.

23. Letter from Captain Harold Robinson to Kitty, 11 September 1916.

24. London Gazette Supplement 8870, 9 September, 1916; Sussex Daily News, 3 May, 1917.

25. Unsigned or dated letter held in collection at Wet Sussex Record Office.

Photo credits: Geoffrey Baker, Margaret Smith and Nigel Higson. The picture of Nelson boxing appears in an unknown newspaper, possibly American, dated 7 July 1917.

This story was submitted by Michelle Pollard, Langney Primary School