During WW1 thousands of British nurses were dispatched around the world to care for wounded soldiers. Yet, thousands of civilian nurses, trained as midwives, remained in Britain to provide maternity care and continue the progress made in this sector in the lead up to WW1.

It is well known that military nurses played an imperative role in WW1, tending to the hundreds of thousands of soldiers badly wounded on the front lines. The Queen Alexandra Imperial Military Nursing Service formed the largest group of military nurses and, by the end of the War, thousands of British nurses had been dispatched around the world to care for wounded soldiers. However, what is perhaps less well known is the story of the civilian nurses that stayed at home, cared for the sick and delivered the children of the women that remained in Britain.

Queen’s Institute Nurses attending a visit at Marlborough House in 1901 – Image courtesy of the Queen’s Institute

At the beginning of the 20th Century, midwifery was a vastly unregulated profession, so much so that any woman could practice midwifery without training or qualifications. This changed, however, in the run up to the First World War when growing attention was given to child and maternity welfare. The 1902 Midwives Act established the Central Midwives Board and dictated that a woman could not call herself a midwife unless she was certified by the Board or she risked being fined up to £5 (the equivalent of around £500 today). Further progress was established in 1910 when the loophole in the Act that allowed women to practice as midwives as long as they didn’t call themselves midwives was closed, and the fine for practicing uncertified was increased to £10 (the equivalent of around £1000 today).

Therefore, during WW1 in East Sussex, midwifery was usually provided by certified district nurses that had undertaken the required training. Many district nurses were voluntary, although some received a small salary after they trained in return for committing to a period of service, and they were organised into local nursing associations which were then coordinated by a paid nursing superintendent. In East Sussex, all local Associations fell under the umbrella of the Sussex County Nursing Association. The 1902 Act also made local authorities the local supervising authority over midwives, so the East Sussex County Council (ESCC) Public Health Committee worked closely with the Association to monitor the work of midwives and grant midwifery training scholarships to interested district nurses.

The Sussex County Nursing Association was affiliated to the Queen’s Institute, which was a body established by Queen Victoria in 1887 to represent nurses nationally. A Queen’s nurse was expected to have three years hospital training and then a further six months of Queen’s approved district training, which involved learning how to treat and care for patients without the appliances readily available in a hospital. Midwives would then also be expected to undertake training in maternity nursing: 4 months’ worth if they were a previously trained nurse and 6 months’ worth if they were new. Fees for maternity training were around £30 – £40 (the equivalent of around £3,100 – £4,100 today), hence the need for Council training grants.

Queen’s Institute Nurses attending a visit at Marlborough House in 1901 – Image courtesy of the Queen’s Institute

The annual reports of the Sussex County Nursing Association provide an interesting glimpse into how the First World War impacted district nursing and midwifery in East Sussex. The 1914/1915 Annual Report demonstrates that the Association’s leaders were concerned that the War abroad would have a detrimental impact on the work of the association at home. In the report Lord Edmund Talbot MP highlighted ‘the importance of not allowing the many calls made on our thoughts, time and means by the war to lessen the interest shown in the special work of the Association.’ Talbot’s concerns were mirrored elsewhere in the report when it was recounted that subscriptions, on which the Association depended to carry out their work, had fallen since the beginning of the War. Still, the Association accepted that ‘the war has, so far, we are thankful to say, had less effect on the work of the Association than it has had on some other social and charitable work.’ Although they had been lucky so far, there was clearly concern that attention would be drawn abroad when illness still existed and needed to be treated at home.

The final paragraph of the 1914/1915 Annual Report particularly focuses on the possible detrimental impact that the War, through drawing attention and funds away from the Association, could have on midwifery provision in East Sussex. To ensure that the vital service midwives provided was not forgotten, the report emphasised ‘it is now more than ever necessary to keep up the staff of nurses in the county, and the need of the special work now being developed to safeguard infant and child life is rendered still more urgent by the steady drain on manhood of the Empire caused by war.’ In addition to money to fund the Association, it was also vital that district nurses remained, and new midwives were recruited to safeguard the lives of the children that would populate the post-war generation.

Interestingly, although the following year’s 1915/16 Annual Report of the Association highlighted the progress that had been made to improve delivery of midwifery, particularly the effect that the 1902 Act had on decreasing infant mortality, there was still concern that doctors were covering the practices of unqualified and uncertified midwives. Then again, this wasn’t felt to be a pressing issue in Sussex. The report once again raised concern about a fall in subscriptions but still felt that ‘as last year…the war has had less effect on our Association than it has, we fear, had on some other social and charitable work – subscriptions have only fallen £15’ (the equivalent of around £1,500 today).

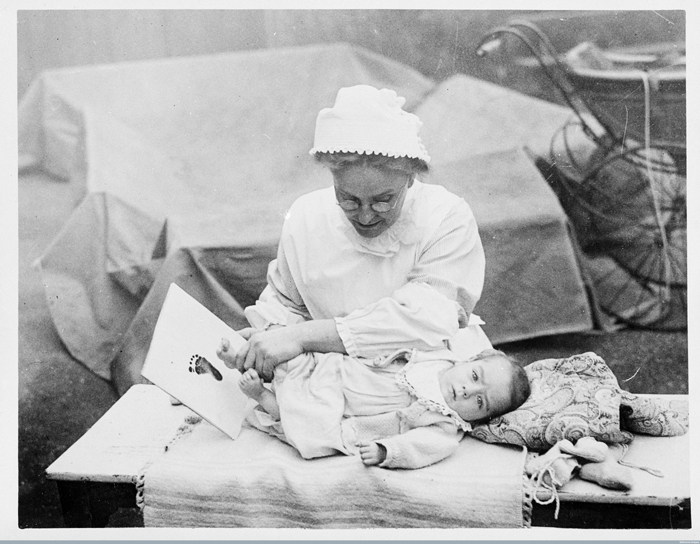

A baby’s footprint being taken by a nurse for identification purposes. Photograph, 1910/1920 – Image courtesy of the Wellcome Library, London

Furthermore, although the Association had shown concerns the year before that they would struggle to retain nurses, the report stated that ‘the Superintendent’s Report shows that the village nurses have again kept loyally, as a whole, to their regular duties in spite of the temptation to undertake more prominent work offered by the war.’ Although the Association’s accounts were in debit (double the amount they opened with), on the whole it was felt that ‘the second year of the war has been weathered fairly.’ The report once again concluded by calling on subscribers to continue to support their work which was now largely directed toward midwifery/maternity services and safeguarding ‘infant and child life while the manhood of the empire is being drained.’

The next year, the 1916/1917 annual report of the Association outlined in further detail what work the Association was undertaking to safeguard infant and child life. It stated that the Association was under constant pressure to train up midwives to deliver children, but in addition, the Association was further developing its school for mothers. The school for mothers involved a lecturer providing classes for mothers on how to provide the best support and care for their child. The lecturer also acted as an infant consultant, answering queries about infant health when a doctor wasn’t available.

What is missed from all Association Annual Reports from this period is any mention of district nurses working in a local War Hospital established during the War in Brighton. The October 1914 edition of the Queen’s Institute’s magazine outlines how nurses all over the country adapted during the War and states that a Second Eastern General War Hospital had been established in Brighton Grammar School. More than 100 nurses were employed in the hospital and a quarter or more were Queen’s district nurses. 520 beds were prepared and 300 wounded soldiers arrived from Mons on September 1st 1914. It is unclear why reference to this and the additional demand on local nurses is missed out the Association’s Annual Reports, and it is perhaps a further testament to how key the Association believed midwifery and maternity welfare to be, with their work in this area referenced throughout the reports instead.

Ideal Home Exhibition, England, 1920: a rubber baby being used to demonstrate feeding methods, watched by two boys. Photograph, 1920.

1920 – Image courtesy of the Wellcome Library, London

Following the end of the War, further provision for the training of midwives was introduced by the 1918 and 1936 Midwives Acts. The 1918 Act also required local authorities to set up a committee for maternity and child welfare matters. The resulting ESCC Maternity and Child Welfare Committee assumed the Council’s responsibilities for monitoring midwifery practice in East Sussex. In December 1918 the Committee abolished the £45 grant limit for nurse midwives, thereby encouraging more nurses to train as midwives by providing suitable financial support, and approved the employment of part-time midwives, thereby increasing flexibility of the role. Both of the measures suggest that in the inter-war years, recruitment and retainment of midwives continued to be regarded as important in East Sussex. The Maternity and Child Welfare Committee remained in place until 1948 when the NHS was introduced and ESCC delegated responsibility for provision of home nursing and midwifery to local associations.

As for the Sussex County Nursing Federation, in 1918 it was split into two separate East Sussex and West Sussex bodies, as work had increased and it was difficult for one body to coordinate two counties. As a result, the East Sussex Nursing Federation (later renamed the East Sussex Nursing Association) was established. The Federation/Association remained in place coordinating nursing and midwifery in East Sussex until 1970, when the Association handed its delegated functions back to ESCC due to changing conditions in the health service and pending local government reorganisation. The Association was reconstituted as a Trust which carried out welfare work for serving and retired nurses.

Ultimately, district nurses and midwives made a vital and unique contribution to East Sussex during WW1, which serves as a further example of the crucial role women played in maintaining the Home Front. You can read more about the history of district nursing and midwifery on the Queen’s Institute’s website celebrating 150 years of district nursing.