As the war progressed, fresh fruit, vegetables and meat got harder to come by. There were even stories of butchers selling dead cats!

Bread and flour were hard to find and government posters encouraged people to eat less bread (see posters).The winter of 1916 saw a major shortage of flour. It was replaced by dried, ground-up turnips which produced unappetising, diarrhoea-inducing bread.

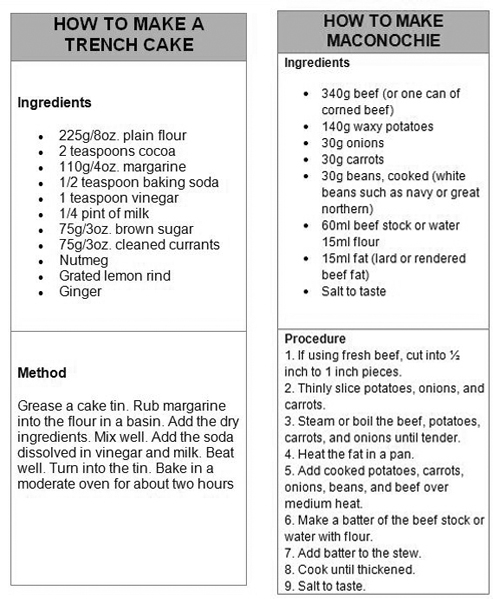

Wartime cookbooks had ideas for recipes that used leftovers and rationed food like ‘potted cheese’ – leftover crumbs of cheese, mixed with mustard and margarine, baked in the oven and served with biscuits or toast. Another recipe used cooked fish, rice, and breadcrumbs to make ‘fish sausages’.

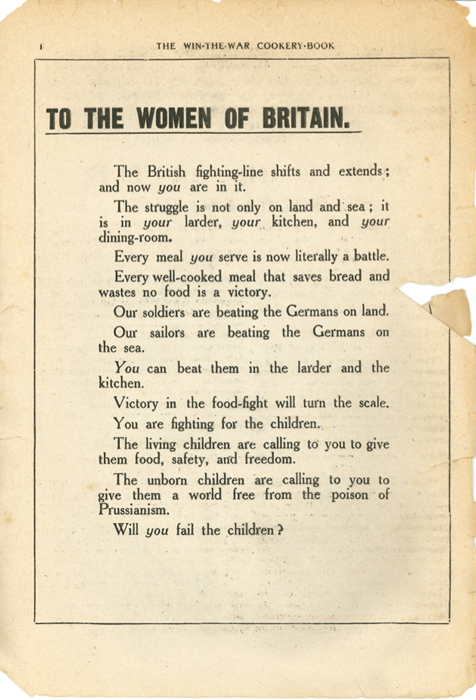

‘The Win-the-War Cookery Book’ carried this message: ‘Women of Britain … Our soldiers are beating the Germans on land. Our sailors are beating them on the sea. You can beat them in the larder and the kitchen.’

In 1918, Britain began rationing to try and make food more equal. Everyone was provided with a ration book that showed how much food they were allowed to buy, including sugar, meat, flour, butter, margarine and milk. Even King George and Queen Mary had rationbooks! Richer families understood what it was like to be hungry whereas some of the poorest families found that rationing left them better-fed than before the war.

Wartime also produced some new foods: dried soup powder, and custard that just needed water adding (like instant custard and soups which are now found in the supermarkets!).

Food in East Sussex

In August 1914, war was declared as the harvest was under way in East Sussex. When war was first declared, it was thought that food supplies would remain unaffected and Sussex farmers would counter increasing corn prices by simply growing more wheat and oats whilst patriotically plough difficult, old and disused war was declared as the harvest was under way in East Sussex. When war was first declared, it was thought that food supplies would remain unaffected and Sussex farmers would counter increasing corn prices by simply growing more wheat and oats whilst patriotically plough difficult, old and disused grassland for human food. By the middle of 1915, however, it became clear that state intervention in farming was required, on a scale never before contemplated!

Arable (crop) farming had declined since 1875, with a generation of farmers growing up with dairying and livestock on grassland farms. This trend had to change quickly, but the workforce was in short supply as young men enlisted and went to war. Horses were being used to assist with ploughing and heavy-duty work. The increased use of animals meant that more animal food had to be imported, but the importation of animal feed and fertilisers was threatened by U-Boat activities, and mechanised farming was in early stages.

Food at the Front

In 1916, the staple food of the British soldier was pea-soup with horse-meat chunks. The hard-working kitchen teams were having to source local vegetables. When they couldn’t, weeds, nettles, and leaves would be used to flavor soups and stews.

Two industrial-sized vats were assigned to each battalion for food preparation. The problem was that every type of meal was prepared within these containers, and so, over time (because they couldn’t be washed properly in between meals), everything started to taste the same. Pea-and-horse flavoured tea was something the soldiers had to get used to!

Food transportation was another issue. By the time it reached the front, bread and biscuits had turned stale and other produce had gone off. Soldiers had to crumble the hard food that arrived and add potatoes, sultanas, and onions to soften the mixture up. This concoction would then be boiled in a sandbag and eaten as a sandy, stale soup.

One widely-used but widely-disliked ration was the canned soup, Maconochie. It was a thin and watery broth containing sliced turnips and carrots, Maconochie was endured by famished soldiers, and detested by all. One soldier summed up the army’s attitude towards it by saying, ‘Warmed in the tin, Machonochie was edible; cold it was a man-killer.’

Of course, to allow the Germans to hear of this desperate food situation would not do. The British Army had to be depicted as a happy, well-fed, strong-minded group whose morale was resolute. An army announcement that British soldiers were being given two hot meals a day, however, caused widespread outrage among soldiers. The army subsequently received over 200,000 angry letters demanding that the grim truth be made public.

Sources:

Food supply during the war by Professor Brian Short, University of Sussex

Home front food – BBC Schools