Both before and during the First World War, the Suffragette movement campaigned for equal voting rights for women. This movement could be seen within East Sussex.

Whilst the campaign for equal voting rights for women is often closely associated with the First World War, it did not begin there.

The women’s suffrage movement first began to emerge as a recognisable force in the 19th century. At that time, voting rights for men were limited, for women non-existent, and the British electoral system in general was heavily under representative. At the end of the 18th century, less than 3% of the population had the vote. By the 1830s, many large and industrial cities did not have a single Member of Parliament representing their population.

Protest and pressure against this situation came through groups such as the Chartists. The Chatrists were primarily focused on improving the voting rights of men. However, there were supporters and organisers within the group who were also in favour of voting rights for women.

The suffrage movement was still in its nascent stage at this point but as the 19th century progressed, so too would the popularity and visibility of the campaign.

Barbara Bodichon

Born Barbara Leigh Smith, in 1827 at Whatlington near Battle, East Sussex, Barbara lived most of her life in Pelham Crescent, Hastings. Barbara was born to her parents out of wedlock and, as a result, was the subject of some scandal at the time. However, her father, Benjamin Leigh Smith, was the Member of Parliament for Norwich and he provided Barbara with a strong education and then investments which brought her £300 per year (£28,000 in today’s money) once she’d turned 21. Her education and financial backing allowed Barbara a degree of freedom and independence that was largely unheard of for women of the time period.

Whilst initially pursuing her dream of becoming an artist, Barbara also became increasingly interested and involved in campaigns designed to highlight the inequalities faced by women. In 1854, she published the pamphlet; A Brief Summary in Plain Language of the Most Important Laws Concerning Women, Together with a Few Observations Thereon. Within its pages, Barbara confronted the discriminatory nature of property and marriage laws towards women.

After marrying the French physician Dr Eugene Bodichon in 1857, Barbara followed her pamphlet by setting up the English Women’s Journal in 1858, and by assisting in the creation of the Society for the Promotion of Employment for Women in 1859.

Barbara then turned her attention to the matter of votes for women by supporting the parliamentary election campaign of John Stuart Mill, who was strongly in favour of women’s suffrage.

In 1877, Barbara Bodichon suffered a stroke which greatly curtailed her ability to campaign for women’s equality. She died in 1891 leaving a legacy as one of the founders of the women’s rights movement.

Women’s Suffrage and the First World War

The Suffragette movement grew in popularity, power, and visibility from the end of the 19th century but still struggled to force the government into producing real change.

The Pankhursts, mother Emmeline and her daughters Sylvia and Christabel, were key participants in leading the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). The WSPU had become increasingly angered and disillusioned by what they perceived to be broken promises and lies on behalf of the British government. In response the WSPU began a series of more militant protests and activities.

These activities included arson, bombings, direct protest action and hunger striking. In one of the most famous incidents, in 1913, Emily Davison walked in front of the King’s Horse at the Epsom Derby to draw attention to women’s suffrage and was subsequently trampled and killed.

In East Sussex, Clementina Black, born in Brighton in 1853, became involved in the suffrage and trade union movements at the end of the 19th century. She passionately campaigned for better working conditions for women, and fought against motions by existing trade unions to bar women from becoming members.

The outbreak of the First World War represented both an obstacle and an opportunity for the Suffragettes. Believing that German aggression was a serious threat to peace and civilisation the WSPU suspended activities at the outbreak of the war, whilst the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies (NUWSS) continued peaceful action during the conflict.

There were those in both organisations that believed that by offering full support to the country during the war, women would be able to win the right to vote as a reward. At the same time, others believed that the need for national unity represented an opportunity for women to essentially bargain voting rights by threatening disruption.

The British need for manpower in the army drastically reduced the workforce left behind in the country. Through necessity, jobs that had previously been denied to women suddenly opened up. Women began to fulfill roles in a variety of industries such as armament production, the postal service, and transportation.

However, resistance from male co-workers and their trade unions meant that women workers were usually paid far less than their male equivalents and jobs of skilled men were subject to ‘dilution’ where they were broken down into multiple unskilled roles which had to be filled by multiple women. This prevented women from replacing skilled male workers in a 1:1 ratio.

In 1915, Clementina Black and the Women’s Industrial Council (WIC) published their research into the working conditions of women in 117 different trades as Married Women’s Work.

At the conclusion of the war, many of the women who had found work during the conflict were immediately dismissed to make way for the returning men.

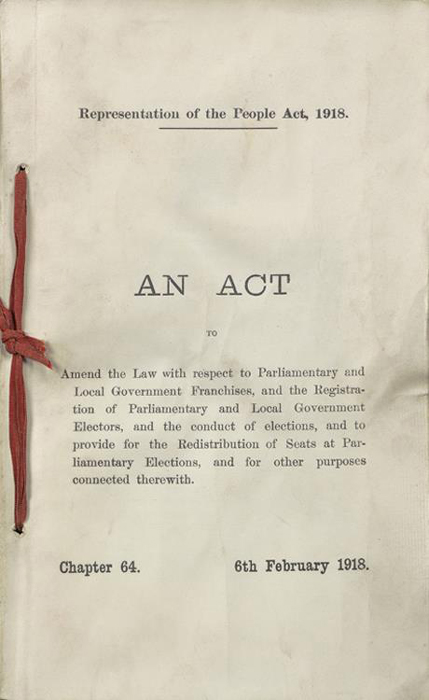

1918 Representation of the People Act

As the First World War came to an end a general election was looming. In 1917, a bill expanding the electoral franchise for both men and women had passed through the House of Commons and was enacted on 6 February 1918.

This Representation of the People Act removed almost all property ownership requirements for male voters and changed residency requirements for them whilst lowering the voting age to 21.

Women over the age of 30 gained the vote if they were property owners, either married to a member of a Local Government Register (which was a list of those who were paying taxes on owned property) or were a member themselves, or if they were a graduate voting in a university constituency.

For some time this change to the electoral franchise was seen as a victory for the women’s suffrage movement and a validation of their policy to actively support the war effort.

However, there remains historical skepticism about this argument. The overwhelming beneficiaries of the new electoral situation were men, who had almost all obstacles removed from them in reward for their war service. Residency rules were altered because of the number of men who had been deployed abroad and, therefore, had not been living in the country during the war.

Additionally, that the age of voting for women was 30 is indicative in itself. Many of those men who lost their lives in the war fell between the ages of 21 and 30. If the right to vote had been extended to women aged 21 and over as it had been to men, they would likely have outnumbered men in this age demographic.

Furthermore, in the years before the war, the activities of the Suffragettes had been building a degree of momentum and power and it has been supposed that if the war had not begun at all, these activities may well have led to a better voting deal for women than that which they ‘won’ as a result of the war.

It would not be until the Representation of the People Act in 1928, that women would gain equal voting rights as men in Britain.

For further information regarding the fight for Women’s Suffrage see the records of the Women’s Library.