At the end of the First World War, a General Election placed voting power into the hands of millions who had never had it before and permanently changed Britain’s political landscape.

The last General Elections before the First World War had both been held in 1910 and both had produced hung parliaments and coalition governments. The two major party groups at the time were the Liberal Party led by Herbert Asquith and the Conservative Party (along with their allies the Liberal Unionists) led by Arthur Balfour. The first election in January of 1910 produced a result of 274 seats for the Liberals and 272 seats for the Conservatives with the rest of the seats being made up by other parties. At the time there were 670 seats in Parliament rather than the modern 650, meaning that 336 seats were required for a majority. Whilst the Liberals had taken the most seats, the Conservatives had won the most votes. Asquith was able to form a government alongside the Irish Parliamentary Party. A second election was called in December 1910 in an attempt to break the deadlock but this time the results was 272 seats for the Liberals and 271 for the Conservatives. Once again, Asquith formed a government with the Irish Parliamentary Party. This was the last election in which neither the Conservative Party nor Labour won the majority of seats until the 2010 European Parliament Elections in Britain.

Whilst reforms to voting rights had progressed further, in 1884 only 60% of male householders over the age of 21, and no women at all, held the vote in 1910. In 1910, there were only 7.6 million enfranchised voters in Britain and this number held steady during the First World War. The Parliament Act of 1911 also acted to reduce the term of Parliament from 7 years to a maximum of 5. This meant the next General Election was scheduled for 1915.

Parliament in the First World War

The outbreak and escalating seriousness of the First World War soon led to the suspension of elections for the duration of the conflict. Herbert Asquith (of the Liberal Party) would continue in his role of Prime Minister but his control of Parliament and the Cabinet was under pressure even from the very beginning of the war. Since 1905, Britain had been engaged in secret talks with France over the possibility of cooperation in the event of a war with Germany. So secret were these talks that many members of Asquith’s own Cabinet did not know of them until after 1911. In that same year, Lord Crowe of the Foreign Office had been forced to reassure Parliament that the Entente Cordiale agreement did not require Britain to do anything in the event of war between France and Germany. Whilst, strictly speaking, this was true both Crowe and Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary, believed that the agreement represented both a moral and a strategic requirement for Britain to enter the war on the side of France.

Arguments split the Cabinet during July 1914 over whether Britain’s interests would best be served by maintaining neutrality or by joining the military effort against Germany. Whilst the decision to eventually join the war was taken, both Asquith and Grey came under fierce criticism for their handling of the affair and Charles Trevelyan, the Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Education, resigned from the government rather than be a participant in the war.

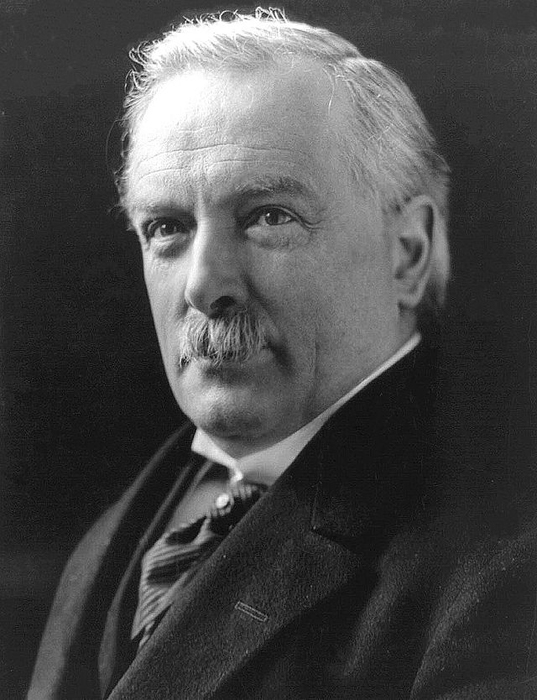

Asquith’s government continued to hold power at the start of 1915 but matters began to deteriorate thereafter. Strong criticism of the government’s handling of the shell crisis and the attack on Gallipoli weakened Asquith’s position. He avoided calling a new election and instead formed a new coalition government between his own Liberal Party and the Conservatives. This coalition would only hold together until 1916. The Battle of the Somme had added to the ongoing criticism of Asquith’s leadership during the conflict and culminated with the collapse of his government. A new Conservative majority government was formed but at its head was the Liberal politician David Lloyd George. Lloyd George had previously served as Minister for Munitions and Secretary of State for War and was viewed as having far greater clout and leadership potential than any of the Conservative alternatives.

It would be Lloyd George who would then lead Britain for the remainder of the war and, at its conclusion, immediately call a new election.

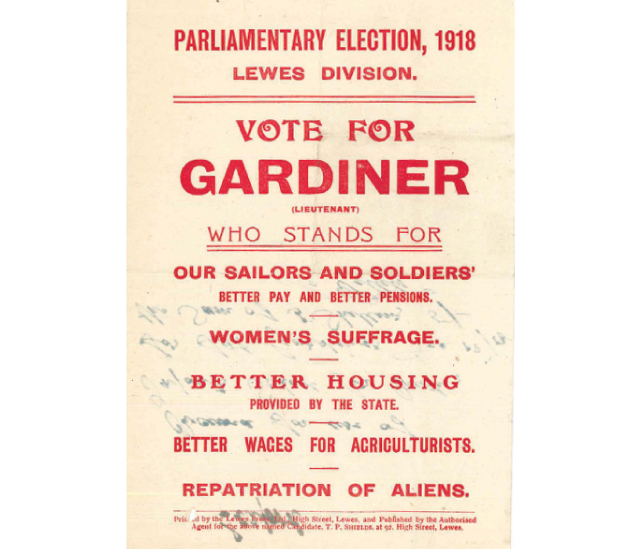

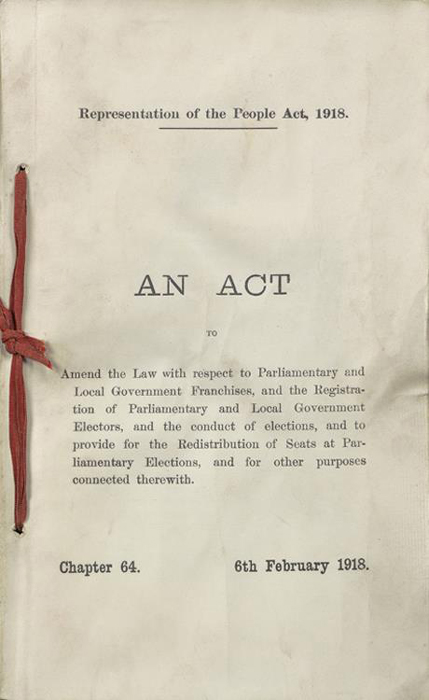

East Sussex votes

At the start of 1918, new legislation entitled the Representation of the People Act extended voting rights to different of society. For the first time, all men aged 21 and over were afforded the vote. Additionally, the vote was given to women over the age of 30 who either owned property; were a university graduate within a university constituency; or who were either a member of the Local Government Register or married to someone who was a member. The notion that it was the service of women during the war that won them the vote is an idea that has been controversial amongst historians. Women younger than 30 were also restricted from voting to avoid causing a noticeable shift in the electorate. Most of the casualties suffered during the war had been from men aged between 18 and 30 and, as a result, there was an imbalance between surviving men and women in that age bracket. However, at the time of the 1918 General Election there were 21 million eligible voters within Britain.

The election itself was held on the 14 December 1918 but the counting of votes would not be held until after Christmas to ensure that soldiers still serving abroad would be able to return their ballots. Lloyd George led a coalition Liberal and Conservative Party into the election and both he and the Conservative leader offered ‘Coalition Coupons’ which were signed letters of endorsement, to Liberal and Conservative candidates. Some candidates turned down this endorsement and, as a result, found themselves open to accusations of a lack of patriotism.

The Liberal Party itself split into two camps during the election. The coalition members under Lloyd George formed one camp whilst those Liberal members loyal to Asquith formed the other.

Voters in East Sussex often returned their coalition endorsed candidates. Eastbourne voted in favour of Rupert Gwynne from the Conservative Party. William Campion of the Conservative Party was returned from Lewes. The coalition endorsed Conservative candidate for Hastings, Laurance Lyon was also elected. Meanwhile, Brighton returned two coalition Conservative candidates in George Tryon and Charles Thomas-Stanford.

Aftermath

The 1918 General Election produced a landslide victory for the coalition. Lloyd George continued as the Prime Minister despite his Liberal members being outnumbered by the Conservative party by 332 seats to 127. The Liberal Party members who had not supported the coalition were almost wiped out and were left with just 36 seats. Herbert Asquith, the former Prime Minister, was one of those who lost his seat in the election. Likewise, the Irish Parliamentary Party were also wiped out, replaced by elected members of Sinn Féin in the final election before the creation of the Irish Republic.

Never again would the Liberal Party hold a majority government in the British parliament. The election did prove to be a breakthrough for the Labour Party, however, who increased their number of seats to 57. In future elections, the Liberal Party would collapse and the Labour Party would rise to fill the vacuum.