Propaganda image of Brighton Clock Tower if it were attacked by Zeppelins – Courtesy of Seaford Museum

At the outbreak of war in 1914, Britain began the process of sending soldiers to France. But the fear of a German invasion of Sussex meant defenses had to be assembled and ready.

The fear of invasion by a European power was not a new phenomenon in 1914. Since 1871 (and the conclusion of the Franco-Prussian War), the British people had increasingly been reading a genre of fiction novels now collectively as ‘Invasion Literature‘. The stories of these books all followed a similar formula; Britain had grown lax whilst European nations gazed upon it with envious eyes. Huge complicated spy networks had infiltrated British society and, seemingly without warning, enemy soldiers were landing on the coast and making for London. In some versions Britain would be conquered and humbled, whilst in others they would defeat the invaders at the last moment, sometimes with the help of plucky school children who had been able to see through the schemes that adults could not.

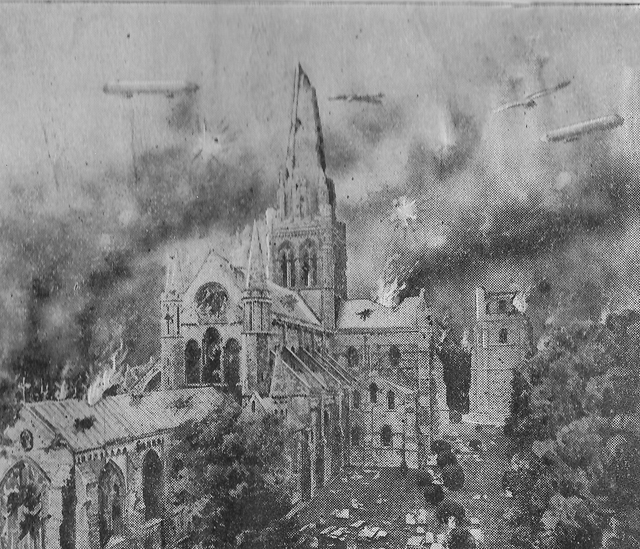

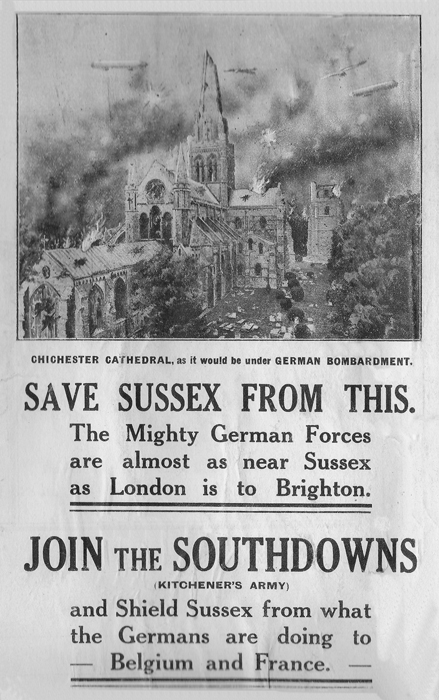

Propaganda image of Chichester Cathedral if it were attacked by Zeppelins – Courtesy of Seaford Museum

The invading power often changed in these stories, alternating between the French, the Germans, and occasionally the Russians or Americans. However, in the run up to war in 1914 the Germans had steadily become the predominant recognised threat. Whilst the Royal navy was still Britain’s strongest source of defence, when war came and the German army invaded Belgium and then France and were heading for the Channel Ports, it became clear that defending the south coast would be crucial in ensuring the safety of the country.

Defending the Coast

Immediately following the outbreak of war in 1914, key locations around the East Sussex shore were immediately manned and defended. Newhaven Fort was occupied by soldiers of the Royal Garrison Artillery, whilst the 4th Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment were assembled in Newhaven and began guarding the swing bridge, harbour and quays. The 2/5th Battalion (Cinque Ports), Royal Sussex Regiment were also deployed to Hastings in November 1914 to defend the ports. There were ongoing concerns that, if an invasion were to come, it would be ‘unheralded’ along stretches of the south coast. Further Territorial units were deployed along goods yards and circular tram routes between Newhaven and Hastings.

To assist in the work of guarding Newhaven Port, Boy Scouts began volunteering to serve as messengers and to assist in keeping watch, and therefore freeing up soldiers for other tasks. When it became clear that the war would not be over swiftly, it was agreed that in exchange for their services these Boy Scouts would each be paid one shilling a week. Scouts would become increasingly involved with the war on the home front as it continued, either acting as assistance to the military establishment or in hospitals and other organisations. A great number of scounting leaders would also serve in the army during the war, and many gave their lives.

In the event of invasion, plans were made that detailed the likely lines of defence and routes of evacuation away from the coast for civilians and refugees. Undefended ports, such as Rye, would be blocked and all boats in the harbour sunk. Livestock, vehicles and provisions would leave the county in the direction of Berkshire and Buckinghamshire.

If vehicles were not able to be moved, precise instructions were given on how to make them inoperative, either by smashing the cylinders, removing vital parts of the mechanism, or slashing the tyres. This would prevent them falling into enemy hands and being used to speed the invasion.

A ‘Most Improbable’ Invasion

Whilst preparations were made for the defence of East Sussex, as the fighting in France settled into trenches, it became clear that the actual likelihood of invasion was slim. Neither side seemed on the verge of a decisive breakthrough on the Western Front that would eliminate the other army and leave them free to move huge numbers of men. Before the Battle of Jutland in 1916, the German High Seas Fleet had been unwilling to risk fighting the Royal Navy and was therefore in no position to assist an invasion. Even after Jutland, the lack of resolution to the battle meant that the naval status quo remained.

Despite this, it was still viewed as important to remain vigilant as to the possibility of invasion and, given the proximity of East Sussex to the fighting in France, the dangers of a German attack were heavily utilised for propaganda reasons. At the beginning of the war, the German navy had shelled Scarborough and bombing raids by German Zeppelins and Gotha Bombers had caused the deaths of numerous civilians. Whilst it was not on the same scale as the Blitz of the Second World War, Britain was still under attack from the air.

Propaganda image of Brighton Town Hall if it were attacked by Zeppelins – Courtesy of Seaford Museum

East Sussex was close enough to France to regularly hear the fighting and, as a result, was also thought to be especially vulnerable to a potential air raid. Seaplanes stationed at Newhaven acted as defence for the port from both air raid and U-Boat attack. Airships launched from the Royal Navy Air Station at Polegate would also provide reconnaissance above and beyond Sussex.

The war would eventually conclude without Sussex being subjected to any form of invasion or prolonged attack from the air. However, many of the plans and approaches to the defence of East Sussex during the First World War would need to be resurrected and updated twenty years later.

Sources

Sussex in the First World War by Keith Grieves