The battlefields of the First World War are filled with tragedies and lost lives. This is the story of the worst moment in Sussex’s military history and the day its men died.

The sound of artillery at the outbreak of the Battle of the Somme could be clearly heard on the Sussex coast. The noise of the guns routinely drifted across the channel and could be heard as far in land as London on some days. The sounds of fighting were particularly loud on 1 July 1916 as men rose from trenches to face the single worst day in the history of the British Army. By sunset, 57,470 men had become casualties, of which 19,240 were dead.

Sussex’s worst day had, however, taken place 24 hours earlier.

Preparing for Battle

The Battle of the Somme was not an isolated event. Whilst the main attack was launched on 1 July, the battle had really begun on 24 June with the opening of the artillery bombardment. The guns were charged with breaking the German wire and destroying the fortifications and morale of the soldiers across No Man’s Land. Bad weather pushed the infantry assault back by 48 hours to 1 July.

Hiding such a large scale offensive from the German army was not a simple task but British high command was keen to try and draw away as many of the German defenders as possible by launching diversionary attacks elsewhere along the front.

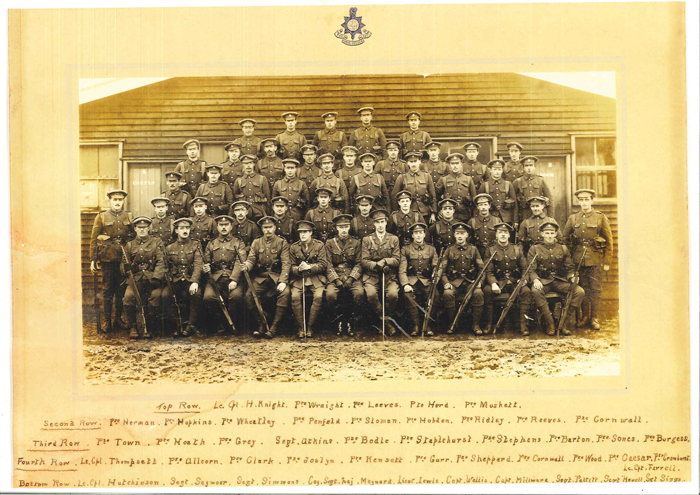

The battle at Ferme du Bois near Richebourg has largely passed out of popular memory. It is not mentioned in the Official History of the War for Britain and, coming a day before the infantry attack on the Somme has become heavily overshadowed by the fighting there. The men of the 11th, 12th and 13th Southdowns Battalions that would lead the fighting there were unaware that their assault was a diversionary raid. Their objective was the nearby salient, a bulge in the line, known as ‘The Boar’s Head’ and it was to be ‘bitten out’.

Before the attack could even be launched problems were afflicting it. The Southdowns had been taken to a constructed replica of the battlefield from which to train on. This ‘fake’ battlefield also drew attention to the numerous drainage ditches in the area, including one immediately beyond the British trenches. It may also have neglected to include a large dyke running through the centre of no man’s land. This training lasted only a few days.

Upon learning of the plans for battle, Colonel Grisewood, commander of the 11th Battalion, famously declared that ‘I am not sacrificing my men as cannon-fodder’. Grisewood was promptly relieved of his post. Grisewood had already lost one brother during the war to illness. He would lose another at the Boar’s Head.

Attack on the Boar’s Head

The 12th and 13th Battalions were given the responsibility to lead the attack with the 11th Battalion, having had their role reduced following Grisewood’s dismissal, tasked with providing carrying parties. At 3:05am on 30 June 1916, the Southdowns went over the top.

The Germans had known they were coming for several days and, as would be discovered in 24 hours at the Somme, the artillery bombardment at Richebourg had had little affect on the German wire. As a result, the attack was a disaster.

Whilst bridges had been laid out to aid in crossing the drainage ditches, it also meant that crossing this obstacle meant that even German guns firing blind could catch men in the open. Those men who managed to clear No Man’s Land soon found themselves caught in the smokescreen that was supposed to blind the Germans and were unable to see where they were going. The war poet, Edmund Blunden, who witnessed the attack also reported that men had become trapped in the hitherto unnoticed dyke. As British soldiers reached the German trenches the fighting descended into brutal pitched hand to hand fighting until the British were eventual driven out.

Company Sergeant Major Nelson Carter single-handedly captured a German machine gun post and used the weapon to cover the retreat of his fellows before fleeing German trenches himself. He then repeatedly re-entered No Man’s Land to rescue wounded men and carry them to safety. On his final trip he was shot through the chest and killed. He was posthumously rewarded the Victoria Cross for his bravery.

Other awards for the Southdowns included twenty Military Medals, eight Distinguished Conduct Medals, four military crosses and a Distinguished Service Order.

These awards were not greeted with much enthusiasm. Blunden, who had volunteered for service with the 11th Battalion of the Southdowns at the outbreak of the war, declared that upon hearing of the real reason for the attack that ‘the explanations were almost as infuriating to the troops as the attack itself’.

Aftermath

When the time came to take stock, the casualty numbers were tremendous. The 11th Battalion had sustained 116 casualties whilst supporting the attack. The 12th Battalion lost 429 men either killed or wounded. The 13th Battalion, however, had been almost entirely destroyed with over 800 men being killed, wounded or captured. In total, the three Southdowns Battalions suffered 366 killed and over 1000 wounded or taken prisoner. The majority of officers and Non-Commissioned Officers (NCOs) in these positions were among the casualties. Around 70% of those that died came from Sussex with estimates including up to 12 sets of brothers.

The Southdowns Battalions would be rebuilt over time but they would lose much of their Sussex identity with recruits being brought in from across the country.

The majority of those Sussex men who were killed are buried at cemeteries near Richebourg.

Over the course of the First World War centenary, a number of new memorials have been unveiled linked to the Battle of Boar’s Head.

Chatsmore Catholic High School in Worthing helped in the creation and placement of a memorial at Beach House Park, Worthing on 30 June 2016. A Victoria Cross Paving Stone Memorial was placed in Eastbourne to commemorate Nelson Carter, and on 30 June 2017, a memorial was unveiled in Brighton to commemorate the battle.

- Beach House Park, Worthing

- Nelson Carter VC – Commemorative Paving Stone

- Boar’s Head Memorial, Brighton

Sources

Bloody British History: Brighton by David J. Boyne

Blighty Brighton by Michael Corum

Lowther’s Lambs by Keith Grieves

The Day Sussex Died: A History of Lowther’s Lambs to the Boar’s Head Massacre by John A. Baines

Undertones of War by Edmund Blunden

West Sussex Record Office, Chichester

This story was updated in June 2016