The following information is for teachers to utilise in planning classroom activities.

With manpower shortages hampering the war effort, the British Army looked to China in order to find able workers.

1915 was the worst year of the war for Britain and France. The casualties sustained in battles at Ypres and Gallipoli had brought little success and cost the British Army so much that the start of 1916 saw the introduction of forced recruitment through conscription.

Beyond the need for fighting men, however, was the additional need for men to provide labour at various supply depots and ports both in Europe and Britain.

The French initially attempted to solve this problem with the foundation of their own Chinese Labour Force in May 1916. They hired 40,000 Chinese men to serve with their army and hundreds of Chinese students to serve as translators. Shortly after the French had launched their project, the British followed suit by creating a recruitment base in the British colony of Weihaiwei (now the city of Weihai, Shandong Province) in October 1916.

China was a neutral country at the time and citizens were forbidden from fighting in the war by their government. Working as labourers however, was permitted and around 95,000 men would join this British Corps over the remaining course of the war.

Life in the Chinese Labour Corps began under terrible conditions with men sailing across the Pacific Ocean and then, to avoid landing taxes at Canadian ports, travelling for 6 days across Canada in sealed trains. By the time they sailed across the Atlantic and then journeyed by train down the length of Britain, many of the men who had set out from China had died.

Every man who joined the Labour Corps was assigned a number that replaced their name for the duration of their service. Whilst translators were on hand to explain orders to the men, British officers referred to each Chinese labourer by the numbered wristband they wore and it was reproduced on the headstones of those men who had died.

Men who had joined the Labour Corps lived under the restrictions of Military Law and were contracted for a duration of 3 years. It was not uncommon, therefore, to see groups of Chinese labourers continuing to work on the abandoned battlefields in 1919 and 1920 long after the soldiers had departed them and returned home.

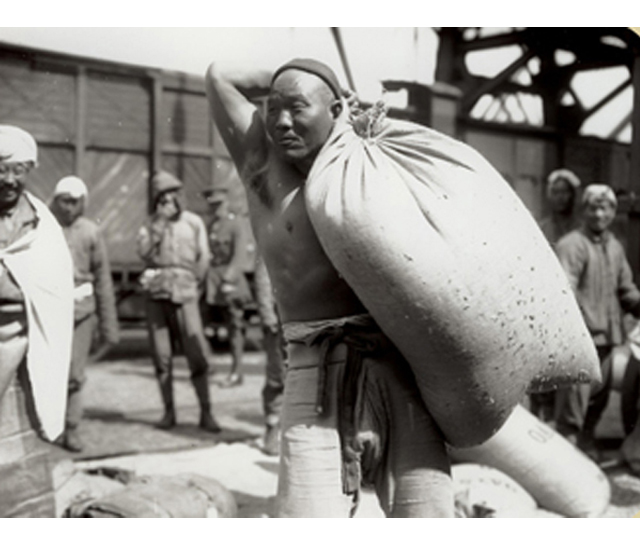

Duties for men in the Labour Corps included digging trenches, filling sandbags, building huts, repairing roads, loading and unloading vehicles and munitions, and even cooking.

The port of Newhaven was the key supply point on the East Sussex coast. Chinese Labourers became a common sight in the town as they worked on the dockside and handled the train-ferry to Dieppe.

China officially declared war on Germany in 1917 after a U-Boat sunk the French ship Athos at the cost of 543 Chinese lives. Britain and France had promised China that they would ensure the Shandong Peninsula would be returned to them from the Japanese if the war was won.

During the negotiations at the end of the war, this promise was not kept and, as a result, the Chinese refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles which brought about the end of the war and dictated the terms and cost that Germany and its allies would have to pay.

Most Chinese labourers returned home in 1920 with a small number remaining in France.

Official statistics suggest that around 2,000 men of the Chinese Labour Corps lost their lives but modern estimates place the actual number at around 20,000.

Questions to ask your students

1) Which country first started hiring Chinese labourers during the war?

2) What duties did Chinese labourers perform during the war?

3) When did Chinese labourers return home?

Images

- Chinese Labourer at Boulogne. Image courtesy of Brighton & Hove Black History Group

- Chinese Labourers at Boulogne. Image courtesy of Brighton and Hove Black History

- Chinese Labourers loading ammunition. Image courtesy of Brighton and Hove Black History

- A Chinese grave at Le Quesnoy, France

Click here to download a copy of this resource: First World War – Chinese Labourers – teachers