The celebration of ‘Bonfire Night’ remained popular in East Sussex during the 19th and early 20th centuries. However, the onset of war in 1914 brought about laws that threatened the continuation of this tradition.

Events marking the anniversary of the failed gunpowder plot of 1605 have been a staple of many British communities for decades if not centuries. The 5th November was often met with torchlight parades through town centres, the building of bonfires, and the releasing of fireworks.

Several of the famous Lewes Bonfire Societies date back to the mid 19th century and the town is still renowned for the huge crowds who gather each year to mark the event.

When Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, new legislation would bring these festivities to an abrupt end.

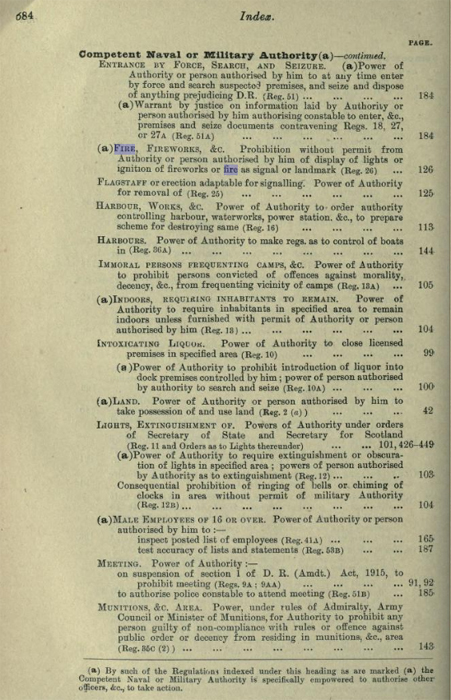

Excerpt from the Defence of the Realm Manual (August 1918) detailing the restrictions on signals and fires

Defence of the Realm Act

Originally introduced on 8 August 1914, mere days after the declaration of war, the Defence of the Realm Act (DORA) was designed to ‘secure public safety’ by protecting Britain from the possibility of invasion and helping to bolster morale on the home front. The original act was further amended on 28 August 1914, and then again on the 27 November 1914, with this latter version becoming the conclusive and binding format of the law.

At its heart the legislation composing DORA was designed to protect the country and ‘His Majesty’s forces’ from any interference by the enemy. Many of the declarations within DORA initially seemed to be fairly broad but it was this breadth that enable the Defence of the Realm Act to have far-reaching consequences.

The final act included the following text:

(1) His Majesty in Council has power during the continuance of the present war to issue regulations for securing the public safety and defence of the realm, and as to the powers and duties for that purpose of the Admiralty and Army Council and of the members of His Majesty’s forces and other persons acting on his behalf; and may by such regulations authorise the trial by courts-martial, or in the case of minor offences by courts of summary jurisdiction, and punishment of persons committing offences against the regulations and in particular against any of the provisions of such regulations designed:-

(a) to prevent persons communicating with the enemy or obtaining information for that purpose or any purpose calculated to jeopardise the success of the operations of any of His Majesty’s forces or the forces of his allies or to assist the enemy; or

(b) to secure the safety of His Majesty’s forces and ships and the safety of any means of communication and of railways, ports, and harbours; or

(c) to prevent the spread of false reports or reports likely to cause disaffection to His Majesty or to interfere with the success of His Majesty’s forces by land or sea or to prejudice His Majesty’s relations with foreign powers; or

(d) to secure the navigation of vessels in accordance with directions given by or under the authority of the Admiralty; or

(e) otherwise to prevent assistance being given to the enemy or the successful prosecution of the war being endangered.

Through this legislation the government and military were able to outlaw particular possessions such as binoculars that could be used to spy upon naval ports. It was made illegal to loiter in or around bridges and tunnels in case of attempted sabotage.

Further to this, the institution of blackouts to hamper the activities of enemy zeppelins and aircraft, were extended to outlaw the lighting of bonfires and fireworks in case they were used to signal enemy forces.

In one stroke all Bonfire Night activities were made illegal in Britain for the duration of the war.

Lewes Bonfire Societies and the First World War

Before the First World War, it was traditional for societies to meet in September and begin the process of raising funds for the forthcoming Bonfire Night. Following the celebrations each year, remaining money was generally dispersed to local charities.

The introduction of the first drafts of the Defence of the Realm Act immediately ceased any planning by the societies.

Even if these laws had not been passed, the mass recruitment of able bodied young men may well have rendered many of the societies unable to function during the conflict.

Mick Symes of the Lewes Borough Bonfire Society, an organisation that has been running since 1853, reports that there are no records of the society holding any activities during the war years and that, as the war continued, the introduction of conscription in 1916 would have further increased the number of society members departing for armed service. Similarly, many members of the South Street Bonfire Society, which had only formed in 1913, were also moved to join the army.

Throughout the years of the war, the constraints of DORA continued to prevent Bonfire Night related activities in Lewes and other towns in Britain.

The announcement of the Armistice on 11 November 1918 did, however, bring about a celebration involving mass fireworks in Eastbourne, and on 20 November the ‘Bonfire Boys’ of Lewes staged a celebratory parade to mark the end of the conflict whilst also remembering those members who had died or been wounded in the fighting.

After the Armistice

Whilst the war had ended it would still take some time before normal Bonfire Night celebrations would return. The Commercial Square Bonfire Society, originally formed in 1855, voted to disband in 1919 and would not reform and carry torches again until 1922.

Lest we forget

2008 Fireworks display at Lewes bonfire night celebrations, Sussex.

Image by Mark Bridge

The Southover Bonfire Society represented the parish of Southover which had been particularly hard hit by casualties during the war. It did not reform after the conflict until 1923.

In 1920 the members of the South Street Bonfire Society drew inspiration from the recent conflict by marching through the streets of Lewes bearing an effigy of a German accused of ‘murdering’ the British nurse Edith Cavell.

Over time the Bonfire Societies of Lewes and East Sussex recovered from the losses during the First World War, though they would experience similar restrictions on their activities during the Second World War.

The Societies remain an integral part of the county celebrations of Bonfire Night, and early conversations have taken place regarding the possibility of re-enacting the celebratory parade of 20 November 1918, in the town of Lewes in 2018.

This article was written with assistance and information provided by Mick Symes, Lewes Borough Bonfire Society, and Simon Bailey, Secretary of the South Streets Bonfire Society.