When war was announced in 1914, significant efforts were made by the British Government, businesses and community organisations to recruit volunteers to the army. Sources from the University of Sussex’s Mass Observations archive, held at The Keep, provide an insight into attitudes towards compulsory conscription, which was introduced mid-way through WW1 to enlist the vast numbers of men required to fight abroad.

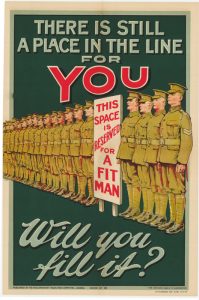

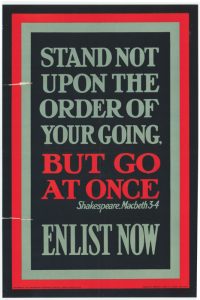

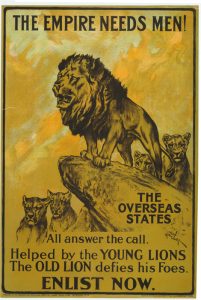

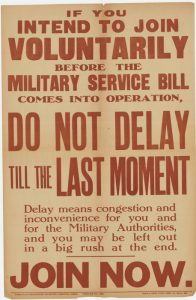

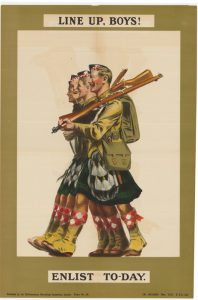

In 1914, the British Army had approximately 710,000 men enlisted and able to fight, and more than 1 million soldiers volunteered to fight in the first months of the war. Lord Kitchener’s ‘Your Country Needs You’ poster campaign is possibly the most famous example of the efforts made to enlist young men in the war effort, but all parts of society worked to encourage young able-bodied men to volunteer to fight. The East Sussex WW1 project has been granted access to a collection of war posters from the East Sussex Libraries archive, which have been digitised and are available to view and download here. The posters in the collection demonstrate the wide range of language, images and evidence used to encourage men to sign up to the army.

Yet, by mid 1915 it was apparent that not enough men were signing up to replace the casualties from the front line. In response, the Derby Scheme was launched in autumn 1915. The scheme involved canvassers visiting eligible men’s houses and asking them to publically declare whether or not they would attest to join the forces. The survey revealed that there were 318,553 medically fit single men eligible to enlist.

Yet, by mid 1915 it was apparent that not enough men were signing up to replace the casualties from the front line. In response, the Derby Scheme was launched in autumn 1915. The scheme involved canvassers visiting eligible men’s houses and asking them to publically declare whether or not they would attest to join the forces. The survey revealed that there were 318,553 medically fit single men eligible to enlist.

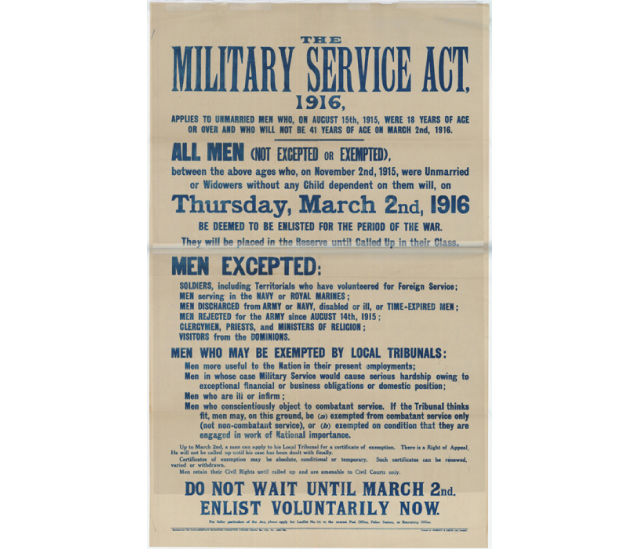

Nevertheless, 38% of single men and 54% of married men publically refused to enlist, and the survey results demonstrated that there was no-where near the number of volunteers required to sustain Britain’s fighting forces. The Military Service Act was subsequently introduced in January 1916 and by March 1916 compulsory conscription for all single men aged 18-41 was in place. In May 1916, the Act was extended to include conscription for married men. Certain men were exempt from conscription: the medically unfit, clergymen, teachers and some industrial workers. Conscientious objectors who objected to war on moral or religious grounds were also exempt. Due to political unrest, conscription was also never implemented in Ireland.

Conscription was not a new concept in 1916. The National Service League was set up in 1902 to lobby the Government and raise awareness of how ill-prepared the British Army was to fight a major war. They proposed ‘national service’ which involved men aged 18 to 30 undertaking four years of compulsory military training. Support for the League grew in the lead up to WW1, and by 1910 the League reported to have 60,000 members. The League was highly politicised and although a number of mainstream politicians voiced support for conscription at one point or another, the National Service League was largely a right-wing movement that hoped to evoke national regeneration following years of political instability caused by the movements for working class and women’s rights.

Attitudes towards conscription in WW1

For over a decade before the First World War, public opinion had been against conscription, and many politicians, including Prime Minister Herbert Henry Asquith, were ideologically opposed to forcing men to fight. In April 1916, over 200,000 people demonstrated against conscription in Trafalgar Square. Further opposition to conscription was evidenced by the fact that by July 1916, 30% of those called up to fight had failed to sign up in protest. Throughout the summer and autumn of 1916, healthy-looking men in public places were rounded up.

There was also a strong class divide in attitudes to conscription. A paper presented to the Government’s Cabinet in September 1915 warned that working men would resist serving a nation in which they had no say over that nation’s governance. Men without property still did not yet have the right to vote in general elections and conscription was seen by some as a theft by capitalist rulers of working men’s rights. A pamphlet published in September 1915 by the Independent Labour Party titled the ‘Perils of Conscription’, argued that the Lords from the ‘higher echelons’ of the National Service League were fundamentally opposed to working-class democracies and were using militarism to regain lost wealth and power. The pamphlet argued ‘among the men whose names are prominently associated with the conscriptionist agitation… I do not know one who has figured as champion of working-class interests or popular freedom.’ According to the author, compulsory conscription would be particularly detrimental to workers who would lose a source of income and the ability to support themselves and/or their family.

There was also a strong class divide in attitudes to conscription. A paper presented to the Government’s Cabinet in September 1915 warned that working men would resist serving a nation in which they had no say over that nation’s governance. Men without property still did not yet have the right to vote in general elections and conscription was seen by some as a theft by capitalist rulers of working men’s rights. A pamphlet published in September 1915 by the Independent Labour Party titled the ‘Perils of Conscription’, argued that the Lords from the ‘higher echelons’ of the National Service League were fundamentally opposed to working-class democracies and were using militarism to regain lost wealth and power. The pamphlet argued ‘among the men whose names are prominently associated with the conscriptionist agitation… I do not know one who has figured as champion of working-class interests or popular freedom.’ According to the author, compulsory conscription would be particularly detrimental to workers who would lose a source of income and the ability to support themselves and/or their family.

Others opposed conscription because they felt it was anti-democratic and that England should resist the temptation of introducing the conscription used by other more ‘brutish’ nations. On 8 March 1916, Eastbourne Gazette printed a letter to the editor from Joseph Solway who claimed his appeal to a military tribunal had been reported incorrectly in a previous edition of the newspaper. While the Eastbourne Gazette had previously reported that Mr Solway had stated at his tribunal hearing that he had no love of England, in his letter he protested: ‘what I said was “I have no love for the conscription methods of England and Russia.” I know what Russian conscription is, and if winning this war means that this country adopts conscription then it is a poor win after all. The pity of it is that England, which has remained democratic in military principles so long, should be forced by the conscription clique to make it law for all “freemen” to throw off their garb of civilisation and revert back to the abysmal brutishness of a country perpetually bearing arms of destruction.’

And then there were those who supported conscription, but recognised it was not the only means to winning the war. Viscountess Wolseley, founder of the Glynde School for Lady Gardeners, also wrote in the Eastbourne Gazette on 8 March 1916 that she believed in the results ‘to be achieved by making all men who are physically fit register their willingness to take part in this Great War.’ Still, Viscountess Wolseley argued that it should not be forgotten that a number of men would need to be retained to work the land and provide food for the nation. She said ‘I am of opinion that those in authority must look upon the proper cultivation of our land and an increased yield of produce, as our secondary line of defence. I regret that the general public do not realise the importance of both agriculture and horticulture as a means of beating our enemy…unless a considerable number of starred men are retained for the land, we shall, even if we win by fighting, have years of poverty and distress to combat. Therefore, by every possible means, this secondary line of defence – agriculture – should be strengthened.’

And then there were those who supported conscription, but recognised it was not the only means to winning the war. Viscountess Wolseley, founder of the Glynde School for Lady Gardeners, also wrote in the Eastbourne Gazette on 8 March 1916 that she believed in the results ‘to be achieved by making all men who are physically fit register their willingness to take part in this Great War.’ Still, Viscountess Wolseley argued that it should not be forgotten that a number of men would need to be retained to work the land and provide food for the nation. She said ‘I am of opinion that those in authority must look upon the proper cultivation of our land and an increased yield of produce, as our secondary line of defence. I regret that the general public do not realise the importance of both agriculture and horticulture as a means of beating our enemy…unless a considerable number of starred men are retained for the land, we shall, even if we win by fighting, have years of poverty and distress to combat. Therefore, by every possible means, this secondary line of defence – agriculture – should be strengthened.’

Reflections on conscription

The Mass Observations project, now housed at the University of Sussex, undertook a study of attitudes to conscription in 1939, when the British Government was considering re-introducing compulsory conscription to increase the size of the British Army for fighting in the Second World War. A number of the responses given to the questions asked by researchers include references to the First World War and provide an insight to attitudes of people when conscription was first introduced in 1916.

As outlined above, some attitudes to conscription were based along class lines. One member of the public responded to the researcher’s question ‘what do you think of conscription?’ with: ‘Most of us were absolutely against it [in 1916], because we thought at first that it did away with the civil liberties of the people. And most important of all, as a working man, what have we got to gain by fighting. Even if the war does start it will be a capitalistic war. The working man will gain nothing out of it. In my opinion conscription has put back the advance of the working man by fifteen years.’

As outlined above, some attitudes to conscription were based along class lines. One member of the public responded to the researcher’s question ‘what do you think of conscription?’ with: ‘Most of us were absolutely against it [in 1916], because we thought at first that it did away with the civil liberties of the people. And most important of all, as a working man, what have we got to gain by fighting. Even if the war does start it will be a capitalistic war. The working man will gain nothing out of it. In my opinion conscription has put back the advance of the working man by fifteen years.’

Other themes are apparent in the responses given. When asked to give their thoughts on conscription, a number of respondents thought it was ‘alright as long as fellows get their jobs back.’

Individual’s experiences of being conscribed or witnessing the conscription of others in WW1 did not appear to make them predisposed to supporting or opposing conscription when re-introduction was proposed in 1939. Some took the opinion that their experience of being enlisted for service in WW1 hadn’t done them any harm. One man answered ‘well I served in the last war. I think it’s a good idea for these young fellows.’ Another woman said ‘I had four brothers in the last one. I think that some of the fellows get a big idea of themselves and training does them good. I have a brother of 26… he’s been spoiled. It would do him good.’ Another woman felt that conscription of young men was ‘better than them going to dance halls.’ For these people, the extensive loss of life to fighting in WW1 did not influence their opinion on conscription. Their views reflected the arguments that had been made by groups such as the National Service League for years: conscription provided moral discipline, industrial efficiency and kept men occupied.

For one respondent, being conscripted in WW1 had been a source of pride. He said: ‘I was 37 when I joined up in 1915 and with 6 months training I put on 6lbs. It is one of the finest things you can have.’ He goes on to reason that conscription improved the effectiveness and capabilities of the British Army, as men fighting in the Boer War often had low levels of fitness and health and were prone to drinking. This, he argued, had been wiped out by the introduction of conscription and the training soldiers received.

For one respondent, being conscripted in WW1 had been a source of pride. He said: ‘I was 37 when I joined up in 1915 and with 6 months training I put on 6lbs. It is one of the finest things you can have.’ He goes on to reason that conscription improved the effectiveness and capabilities of the British Army, as men fighting in the Boer War often had low levels of fitness and health and were prone to drinking. This, he argued, had been wiped out by the introduction of conscription and the training soldiers received.

Still, to some, the memories of the soldiers killed during the First World War influenced their attitudes to conscription in 1939. One woman responded to the question: ‘In the last war I never told one man that he ought to go. I tried to put myself in their place. If I’d been them I wouldn’t have gone. When I saw them going through the streets – all the young men – I used to think that they were being driven like cattle to the slaughter house. And they were, weren’t they? Fodder for the guns.’

The end of conscription in WW1

By the end of the war, over 5 million men had signed up to fight; 2.67 million joined as volunteers and 2.77 million joined as conscripts.

In 1918, in the last months of the war, a further Act, the Military Service (No. 2) Act increased the age range so that conscription applied to healthy men aged 51 and below. Conscription was also extended to 1920 so that the army had sufficient man-power to ‘deal with trouble spots in the Empire and parts of Europe.’

The opinions of conscription referenced in this story are sourced from the Mass Observation archives titled ‘Replies to the question ‘What do you think of conscription?’ (SxMOA1/2/29/1/C/4) and ‘Attitudes to conscription 1939’ (SxMOA1/2/27/1/E/1), and can be accessed at The Keep in East Sussex.