During the First World War soldiers who travelled abroad would often make connections with those they encountered. This is one such story.

In December 1917, British and French divisions were sent to support the Italian army after the defeat at the Battle of Caporetto . Overhung by the fame of the disastrous battle, in Italy the story of the English campaign in Italy was mostly neglected . The arrival of the troops is documented by a precious documentary titled BRITISH TROOPS IN ITALY that is viewable on the Imperial War Museum website.

Camp Vaje was setup at Arquata Scrivia. It became the main the gathering point for British soldiers who arrived in Genoa by sea before the transfer on the Asiago plateau. 36.000 soldiers stayed at Camp Vaje from 1917 to 1920 of whom 94 died of Spanish flu and other military accidents. They were buried in a small cemetery next to the Municipal Cemetery. This site was visited in 1923 by King George V and the Queen, accompanied by Rudyard Kipling, Commissioner for War Graves.

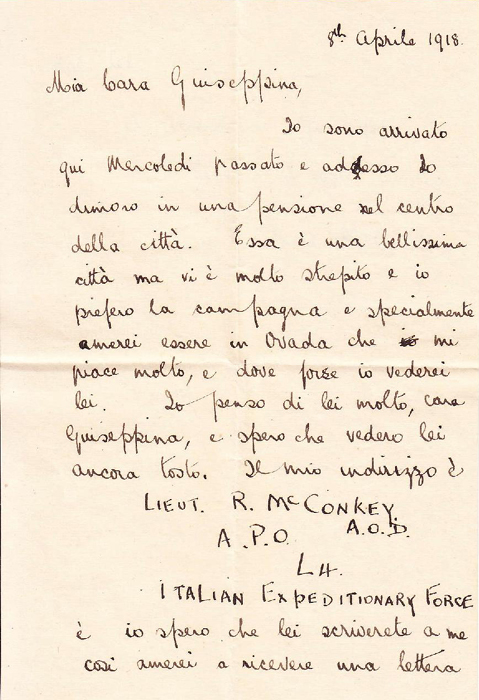

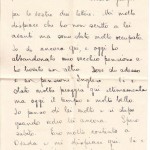

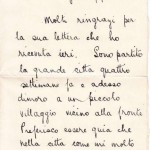

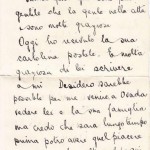

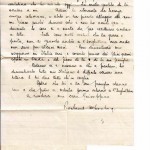

In our archives and in the local press of the time I have not found references to the passage of British troops in my town during the years of the First World War, but their passage is documented by an exchange of letters between a young girl and a British soldier. This correspondence of course started from the moment he left our town to move across the north of Italy and then back home.

The letters in our possession can’t be considered the letters of two lovers; they seem to belong more to the category of “godmothers of war” , but they offer an interesting document on relationships, often with no future, between young women and men in uniform. Letters are often keepers of a sweet melancholy for long walks, talks and perhaps some misplaced hope. Nothing more.

The authors of the letters used to include photographs where they were often portrayed in anonymous, almost shy, poses. It is hard to believe, especially in the case of men, that they were of a young age, at least according to today’s standards.

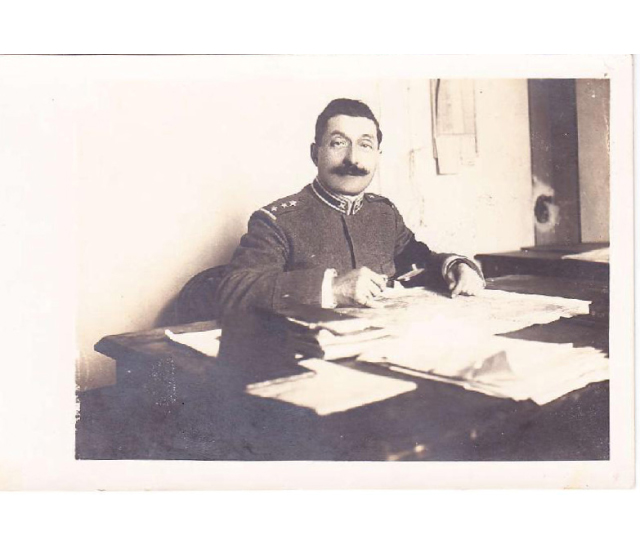

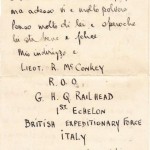

This happened to Leutenant Rowland McConkey who had several exchanges of letters through 1918 with Giuseppina Carosio. When I began getting involved in this story I knew nothing but his name and had this picture. A gentleman with mustache, to whom is difficult to attribute an age, with a mild look diverted from the map which is examining, the magnifying lens in his right hand and wearing a signet ring or Chevaliere.

I knew much more about Giuseppina, born in 1892, daughter of a rich banker and owner of Hotel Universo, an elegant hotel in the city center. She grew up in a interesting and stimulating enviroment as her father wasn’t only a good entrepreneur but also very keen in cultural events, sport and entertainment. Educated first in Ovada, she finished her studies in a college in Massa Carrara, with her sisters Bice and Maria . Her brother, Giacinto, the only son of Carosio family, died in 1917 of tuberculosis contracted while serving in the army. In 1919 Giuseppina got married. It was in 1917 that Giuseppina met Rowland, though we do not know the exact circumstances.

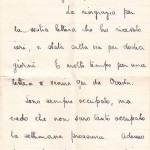

We are ignorant, for example, of Rowland’s location when he wrote his letters wrote, except for 3 postcards sent unequivocally from London. The first postcard, sent on February 27 1918, depicts the British Parliament and it is likely that Rowland had returned home on leave . He writes of the cold weather, confesses to thinking about her and expresses the desire to see her again. He greets her with “ a rivederci”.

On April 8 1918, he writes from Arquata: we know from a postcard enclosed with the letter that portrays Villa Vittoria. He tells of living in a guesthouse in the center of the city, that took profit by the forced stay of the British soldiers: hotels, restaurants, bars, craft shops and local products proliferated. A theatre was erected, the “Victory Theatre.” Rowland calls it beautiful but too noisy: he prefers the country and especially would love to be in Ovada where maybe he would see her. He includes a postscript: I hope that you will write to me so I would love to get a letter. The envelope, in addition to the card, contains the photo I mentioned earlier.

Sweet Giuseppina obviously replied but as to what she said; who knows … We do not have the letters that she wrote to Rowland. Considering the content of British Soldier’s letters, we can suggest that she didn’t overbalance . Something seems to hold her, maybe the fact that Rowland was a foreigner and somehow the family opposed, perhaps she was already engaged. Who knows… All this, anyway, did not prevent them from going on with the correspondence.

And here my research makes a small step forward. I found, after sifting the internet and investing some money, the family status of the McConkey family, the family of Rowland, according to the census of London in 1891. From this source I got further interesting information.

Rowland was born in 1886 in Shipton, in Yorkshire and then, at the time of the photo, was 32 years old : six years only separated him from Giuseppina. Son of William and Mary J. Gordon, he lived in St Paul’s Road, in London, today a quiet and residential street, with his parents, two sisters and an aunt . His father was General Manager of Railways and perhaps for this reason forced to change residence often, in fact the children were each born in a different part of the UK. A similar fate apparently fell to Rowland , in his frequent travels.

May 1 he writes again to Giuseppina, we have reason to believe from Vicenza, thanking her for the two letters he received . He apologizes for not having written before having been very busy. Today I left my old board and I found another, a British one. I was very happy when I was in Ovada, here there’s too much noise and people are not classy. And with these few sentences it is clear that the impression we got from the photo is more than true .

- Post Card – Thiene

- Post Card – Thiene – Reverse of card

- Post Card – Houses of Parliament

- Post Card – Houses of Parliament – Reverse Side

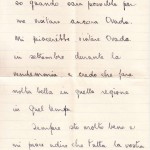

Quiet man, dear Rowland was: it is hard to imagine him among the roar of battle. We suggest he was involved in the distribution of military supplies packed into a train depot. And even a good mannered man as well with discrete culture as he can almost properly manage our language. He reassures Giuseppina about his health and hopes that both she and all your family is fine.

On May 12 he writes about the very hot weather. He’s always in the same English board (temporary address) but hasn’t any contact. He has nobody to talk to and is afraid he’ll unlearn his Italian. He likes the summer costumes of the people who he meets in the crowded streets but he misses people from Piedmont. He writes that they are nicer. In Veneto the dialect is hard to understand and people always talk about money and business.

In a letter of June 16, there is the only reference to the war: I read in the newspapers today that Austrians will begin an offensive, and I hope and believe that will fail.

The battle to which Rowland refers is the one which will be defined by Gabriele D’Annunzio the ‘Battle of the Solstice’, or Second Battle of Piave. The goal of the Austro-Hungarian Army was to break through and reach the Po valley. However, the offensive, as predicted by our dear Rowland, failed , and helped usher in the end of the war .

In July Rowland is transferred to a small village in the countryside, close to the front. It is the town of Thiene, as indicated by the image of Castello Colleoni depicted on the card. He’s happy as he has a motorbike and goes around the country.

In October he writes from London, and from Italy again in December. Only a few soldiers are still there and he feels lonely. But the war is over and everybody’s happy. But he does not seem to be: I forgot all my Italian: is hard to write a letter to you to say all that I want. I will not forget my stay in Italy. Ever.

Those were the golden years of illustrated love cards: kisses posing, “killer” looks, acts of desire just mentioned. Mostly shipped in envelope, to avoid embarrassment. The soldiers at the front were portrayed in uniform and sent cards accompanied by some thoughts of love to girlfriends. Postcards and letters are often rhetorical, they appear ridiculous, ridiculous as are – according to Pessoa – love letters.

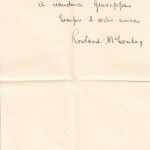

Ridiculous seemed to me the letters of Rowland at the beginning of this story. Although, as I said, they are only letters of “almost” love. Then, over time, I confess that I grew fond of him. For him I wanted a romantic ending, as the natural conclusion of the good times he had here: perhaps he and she reunited after the war, married in St Pancreas in the early 1920s. Rowland dressed in the Royal Army uniform with medals obtained for taking part in the war, Giuseppina dressed in a light and short dress, as required by the post-war women’s fashion, and her granddaughter Tilde as “flower girl”.

Instead Rowland got married in the summer of 1926 to Mary Cheyne Gordon, born in Aberdeen, Scotland, on March 27, 1877. They lived in London, at no. 4 of Camden Square , where Rowland died on 16 May 1940. She passed away, 13 years later, on January 27 1953, at the Hospital of Ashford , Kent. She had retired to the small town of Peacehaven in East Sussex as a war widow.

- Military Roll

- Rowland’s Medal Card

- Notice of death 16 May 1940

What kind of marriage was theirs? Of love of almost love? We can’t say. But I imagine a sort of partnership to cope with old age, loneliness. She, curiously, had the same name as Rowland’s mother, Mary J. Gordon. A coincidence? Almost certainly. But what if he had been looking for protection, or was unable of autonomy? A penny for your thoughts, Mr. Rowland .

Anyway, we have to stop here. They had no direct descendants, perhaps some nephews , children of his sisters. We know however, and this makes us wonder about fate, that a great-grandson of Giuseppina, Elena , now lives not far from no. 4 Camden Square: and his family is credited with having kept all this for themselves, but also a bit for the rest of us .

As a personal note I want to thank Giuseppina (named in honor of the grandmother) called Kiki who handed me the precious letters and game me the confidence and permission to view them. I’d like that this article, written with affection for both, could be considered a small compensation for that shy soldier, whom Giuseppina may have gone on thinking of, although losing some details: just as a kind of a tissue paper between one page and another in the album of her life.

This article was submitted by Cinzia Robbiano

Letters from Rowland