Did you know that during the First World War women’s football was a hugely popular sport and pastime?

At the outbreak of war in 1914, men’s football teams were often used as recruitment adverts and examples to fans. In December 1914, the 17th Battalion (which became known as the ‘Footballers Battalion’) of the London-Middlesex Regiment was created purely to provide a home for amateur and professional footballers who wished to fight for their country. Players from teams such as Liverpool, Tottenham Hotspur and Brighton and Hove Albion soon joined the ranks of this unit.

The FA Cup Final of 1915 was dubbed the ‘Khaki Cup Final‘ but also marked the last point when organised male football was played, as the sport and competition was effectively suspended shortly afterwards for the duration of the war.

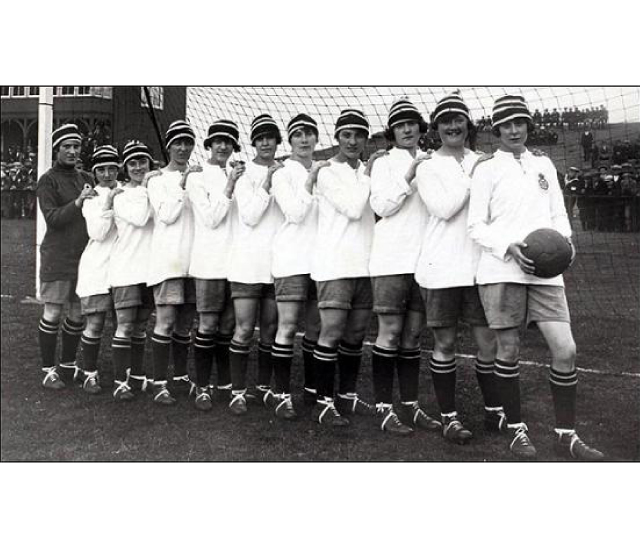

However, this suspension coincided with the emergence of a female workforce for munitions factories and other industrial sectors in order to fill the vacuum left by men who had gone to war. Women had been playing football before the war but the sport had never gained much traction in regards to public acceptance or interest. The relationships and camaraderie formed between women whilst working in the factories would often spill over into friendly and informal football matches. From these roots, the sport became increasingly structured.

Members of the public were missing the enjoyment provided by regular men’s football and this dovetailed with the clear enjoyment that women were taking from the opportunity to form teams within their factories.

By 1917, the Munitionettes Cup had been established and was won by Blyth Spartans. Bella Reay scored a hattrick in the final during a 5-0 victory taking her to over 130 goals for the season. The popularity of the sport did not immediately dim after the conclusion of the war in 1918. Arguably the biggest and most famous women’s team of the period was Dick, Kerr’s Ladies from Preston. Following their foundation in 1917, their first match was attended by 10,000 people. On Boxing Day 1920, 54,000 people were inside Goodison Park, the ground of Everton, to watch them play. Thousands more were locked out of the ground.

At this stage the popularity of women’s football could well have seen it rise to the level and exposure of men’s football in today’s society. However, it was not meant to be.

The return of soldiers from the army was to have drastic consequences on female employment and their opportunity to continue to play football. Many women would lose their jobs in factories and other industries in order to make way for returning men. As part of a wider movement to return these women back to household roles, the view of women’s football began to change. No longer was it seen as beneficial for national morale or as helpful for women’s health. Instead it became viewed as an unhelpful and unsuitable way for women to spend their time and potentially detrimental to their health. This was then compounded by the Football Association’s decision to appeal to all football ground owners to support a ban prohibiting women playing matches at their premises.

Some teams continued to play small games in front of reduced crowds but most women’s teams disbanded or drifted away.

This ban was not lifted again until 1971.

To find out more about women’s football in the First World War see the following sources:

BBC News – Why was women’s football banned in 1921?

Football History Boys: The Rise of Women’s Football 1914-1918