During the First World War, the execution of the British nurse Edith Cavell by Germany proved to be one of the most controversial moments of the conflict.

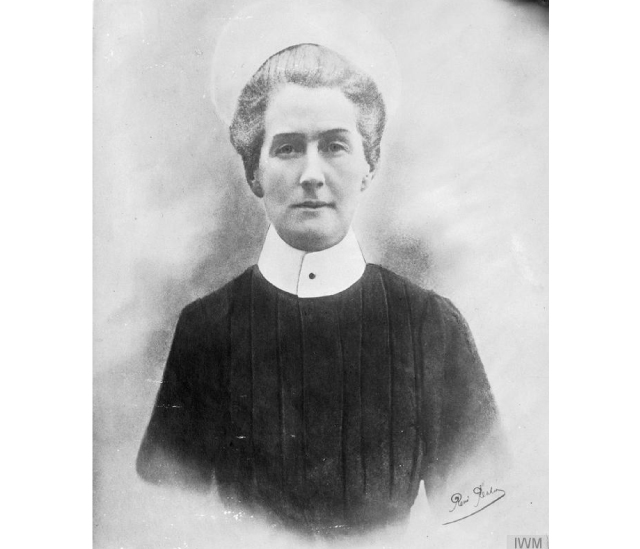

Born in 1865 near Norwich, Edith Cavell was the eldest of four children. Her father was a reverend and a vicar and the importance of charity played a key role in her upbringing. Edith trained as a nurse in London and also spent time working as a Governess for a family in Belgium. In 1907, Edith worked as a Matron at the Berkendael Institute in Brussels. Her primary work was in the training of new nurses and the modernisation of Belgium’s medical care. By 1910, Edith believed that she had raised these standards to a significant level and returned to Britain.

The outbreak of the First World War, would see Edith take a decision to help those in need which would eventually lead to her own death.

Red Cross Service

Pre-War Life in Brussels – A portrait of nurse Edith Cavell as she sits in a garden her two dogs. The dog on the right, “Jack” was rescued after her execution. – © IWM Q 32930

When Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, Edith Cavell was visiting her mother near Norwich. With the news that Belgium was being occupied by the German Army, Edith joined the Red Cross as a nurse. The Berkendael Institute was converted into a Red Cross facility and treated soldiers of all nationalities. It was here that Edith was to return in her new role and she began caring for men from each of the nations involved in the war. This system continued even following the occupation of the city by German forces on 20 August 1914.

However, with the British and French armies in disarray following the Battle of Mons on 23 August 1914, stories began to circulate that soldiers captured by the Germans were being executed, as were those who sought to shelter them. The German invasion of Belgium had brought about a storm of rumours in Britain of wild atrocities, known as the ‘Rape of Belgium‘, being committed. Many of these stories were either untrue or hugely exaggerated. However, it is true that German soldiers held high fears about enemy combatants hidden among Belgian civilians and often reacted with violence and executions at hint of this being the case.

With such a volatile situation unfolding around her in Belgium, Edith Cavell made the decision to begin secretly sheltering Allied soldiers from the Germans during their treatment and, once they were well enough to travel, helping them escape the country. Recovering soldiers, along with Belgian and French civilians who were of military age, were provided with false identification papers by the Belgian Prince Reginald De Croy. From there they were taken to safe houses in Brussels, one of which was run by Edith Cavell. After providing them with temporary shelter and money, these men were then helped to escape across the border into the Netherlands which was a neutral country during the war.

Such actions required huge bravery, as they were in direct contravention of the military law which Germany had established following their occupation of Belgium.In July 1915 the hospital was searched by German soldiers in a bid to uncover any signs that soldiers were passing through the hospital and escaping the country. No signs were found. Edith had covered her tracks and hidden her role in soldiers escape from her fellow nurses.

However, on 5 August 1915, German soldiers returned to the hospital. Edith was informed that they had come for her and she was placed under arrest.

Court Martial and Execution

Edith had seemingly been betrayed by a Frenchman named Gaston Quien. After the war Quien was put on trial by the French for collaboration with the Germans and treasonous acts, including the betrayal of Edith Cavell. Although initially sentenced to death his sentence was instead commuted to twenty years imprisonment and he was released in 1936.

The body of Edith Cavell being taken from the mortuary for transport back to England, 13 May 1919. – © IWM Q 70081

When in captivity, Edith was informed, falsely, that her fellow defendants and conspirators had already confessed. In rersponse Edith confessed everything regarding her role in the escape of around 200 allied soldiers. The reasons behind her full confession remain some source of debate. It is largely posited that either she was unwilling to lie about her activities or, alternatively, sought to save the lives of her companions by taking the lion’s share of responsibility.

Either way the Germans, having obtained the confession they desired put Edith before a military court martial where she was tried and sentenced to death for the crime of ‘helping the hostile Power or of causing harm to the German … troops’, this aspect of the German Military Code covered the act of ‘conducting soldiers to the enemy’.

The announcement that Edith Cavell was to be executed for her crimes caused uproar around the world. The United States of America in particular was deeply disturbed by the turn of events, and their First Secretary of the U.S. legation at Brussels, Hugh Gibson, placed a great deal of diplomatic pressure on Germany to commute the sentence. America in particular told Germany that following the sinking of the Lusitania and the burning of Louvain, that the execution of a nurse would be a grave error. The British government, being in a state of war with Germany, did not feel able to do anything in way of support for Edith.

On 11 October 1915, Edith Cavell was allowed a final communion with an Anglican Priest, whom she told “Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.” The following day she was led from her prison cell and, along with four other Belgian men, was executed by firing squad.

Aftermath

The German government seemed taken aback by the outrage which followed Edith’s execution, and maintained that all involved, including Edith, were fully aware of the consequences of their actions. However, Edith Cavell’s death rapidly became a fixture in wartime propaganda designed to demonstrate both the barbarity of Germany and how important it was to make sacrifices in order to win the war.

- She Gave All, You Buy Peace Bonds – © IWM Art.IWM PST 10635

- Murdered by the Huns – © IWM Art.IWM PST 12217

Edith Cavell’s body stayed in Belgium until after the war was over when it was then transported back to Dover. Her body was then conveyed by train to London before being given a state funeral at Westminster Abbey.

- Memorial to Edith Cavell in St Martins Place, London. Image courtesy of Chris Kempshall

- “Cavell van restored” by Michael Roots

A monument to Edith stands in London to this day and bears the final words she gave to her priest.

The railway van that transported her from Dover to London is currently held at Bodiam Railway Station in East Sussex as a memorial. This railway van also transported the body of the Unknown Warrior from Dover to London in 1920.