On 1 July 1916, the British and French armies attacked the German lines around the River Somme. As that battle raged, an East Sussex filmmaker was in France to capture the footage and create one of the most important documentaries ever seen.

During the First World War, the ability of the press to report on the fighting was heavily controlled by the government and the military. However, there was still a clear desire from the public to receive news and, if possible, footage of the army overseas. At the same time the army was equally keen for those at home to be given a positive view of the fighting in France and Belgium. The result of this was British Topical Committee for War Films, a group created with the aim of producing high quality news reels and films about the war. In November 1915, this group dispatched two filmmakers to France. The first was Hastings resident, Geoffrey Malins, and he was accompanied by Edward Tong.

Between them the pair made five short newsreels which found an audience back home in Britain. In early June , Tong fell ill and was replaced by John McDowell. McDowell left to join Malins in France the day before the British began an artillery bombardment of the German trenches around the Somme.

Filming the Battle of the Somme

The plan to attack the Germans in 1916 had been devised during joint discussions with the military commanders of Britain, France, Russia, Serbia and Italy the previous winter. It had been decided that the British and French armies would attack together at the River Somme in the summer of 1916. However, the German attack on Verdun in February meant that the French involvement in the Somme attack would need to be reduced and the British army would take on more of the effort. In order to soften up the German defensive positions, the British began bombarding enemy lines with artillery fire on 24 June.

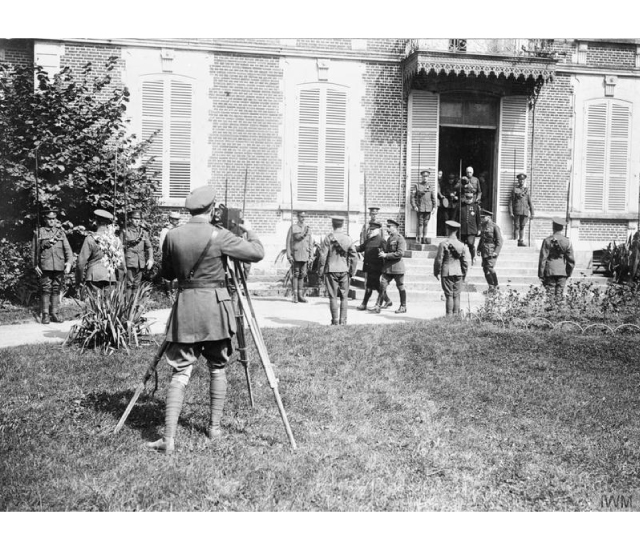

Given the rank of Lieutenant, Malins began the process of capturing the British preparations by himself as McDowell would not arrive and begin filming until 28 June. Malins filmed the bombardment of the village of Beaumont Hamel before the attack on 1 July along with different shots of British soldiers preparing for battle and being inspected by General Henry de Lisle. It was when the attack came in the morning of 1 July that Malins was able to get some of his most iconic footage, particularly the detonation of the a mine at Hawthorn Ridge.

The filming of battle scenes was often highly dangerous and, for some footage, Malins had to rise above the trench parapet and remove sandbags in order to then place the camera into a position where it could record the action. On the first day of the infantry attack a shell explosion actually damaged the tripod of Malins camera and it had to be repaired in order for filming to continue.

Malins briefly left France on 9 July before returning to capture more footage from 12-19 July. It was during this period that Malins also captured some of the most famous, but also controversial footage that appeared in the eventual documentary.

Screening the Somme

On 10 August 1916, at the Scala Theatre in London, the 77-minute long film The Battle of the Somme received its first public screening to a selected audience of journalist and officials from the foreign and war office. By 21 August it was being shown in theatres across London and then, shortly afterwards, the rest of the country. In the first six weeks of its release twenty million people watched it in the cinema. The total population in Britain at the time was forty-six million.

Many members of the public came in the hope of seeing their loved ones on film. Indeed, the Imperial War Museum has since shown the film (recorded with no sound) to lip readers and the most common phrase uttered by the soldiers was; “Hello, Mum, it’s me!”.

However, amongst the hope and brevity, audiences would also see long shots of dead bodies after heavy fighting along with wounded men. But in particular a short collection of scenes proved to be most shocking.

What audiences thought they saw was the very moment that British soldiers advanced out of their trenches only for some of their number to be immediately killed by unseen bullets. Then, filmed at a greater distance British soldiers could be seen swarming over a hillside only for, again, several men to fall down dead. These scenes caused huge shock in the cinema and there were reports of audience members screaming out in horror, crying openly, and even fainting away.

However, all was not as it seemed. The first two scenes in the above clip had actually been filmed by Malins during his second return to France in July 1916 and were almost certainly staged at a British training facility to allow him to capture footage in close up of British soldiers dying. The likelihood of Malins himself being able to film such an attack so closely was highly unlikely as he would also have been in tremendous danger. The image of British soldiers shot at greater distance that then immediately followed the staged footage were absolutely real and had been filmed by Malins on location during the battle.

When edited together they presented a powerful vision of a British army attempting to win the battle whilst many men gave their lives for their country.

Whilst that footage was staged, many other shots, including those of actual dead bodies, were not. Audiences who left the cinema would be left in no doubt about the price being paid for the ongoing war effort.

The film was a huge commercial success and prompted the filming of a later stage of the battle to be released in 1917 as The Battle of the Ancre and Advance of the Tanks. Commercially this second film was a success but not quite to the extent of its predecessor.

Geoffrey Malins released his memoir How I filmed the War in 1920. This book was a heavily edited version of the role he played in documenting the war and completely removed any mention of McDowell.

Regardless, the film The Battle of the Somme remains one of the most important documentaries to have ever been filmed and, in 2005 it appeared on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register, the first British document to be included.