Christmas during the First World War was as much a story of distance as it was of bonding, and this is reflected in the experiences of East Sussex soldiers and civilians.

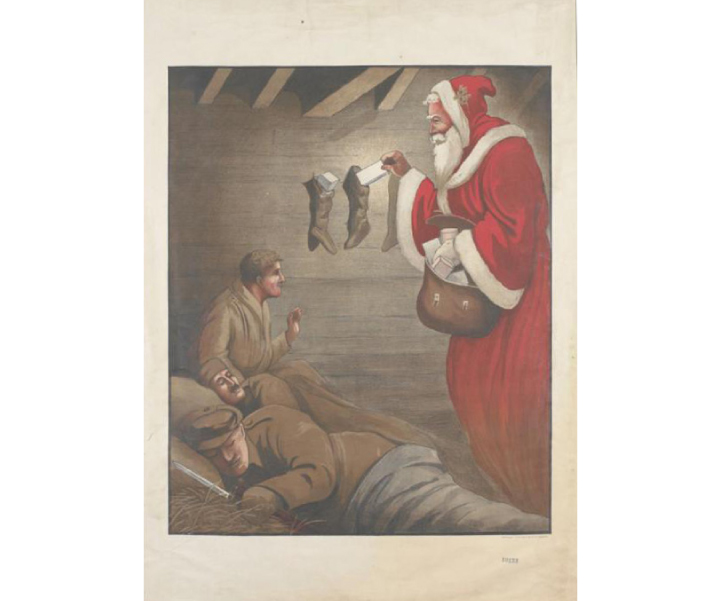

One of the enduring (and indeed endearing) images is the First World War is that of the famous ‘Christmas Truce’ of 1914. What began as the lighting of candles in the trenches grew to groups of French, German and British soldiers seeking each other out in No Man’s Land for the exchanging of gifts, souvenirs and stories. Whilst there were reports of the occasional football match taking place, such instances were far rarer and lower key than we believe them to have been. Some soldiers, such as Horace Marchant, refused to believe that a Christmas Truce had taken place at all.

Sussex Soldiers

For most soldiers, Christmas of 1914 was spent in the trenches or slightly behind the line. An examination of the War Diaries for Royal Sussex Regiments show us how they spent their Christmas. The Christmas Day for the men of 2nd Battalion the Royal Sussex Regiment was ‘spent in peace, the brigade, however being prepared to move at an hour’s notice’.

Even ignoring the Christmas Truce entirely, the festive period brought the opportunity for far greater contact between the soldiers at the front, particular amongst the allied nations of Britain, France and Belgium.

Following the 1914 Truces, the respective allied commands had issued strong orders prohibiting any fraternisation with the enemy and artillery bombardments or small trench raids were also common during the Christmas period. However, this was only focused on preventing the opposing armies from mingling: there was still ample opportunity for allied soldiers to meet each other. Sporting activities between British, Belgian and French soldiers were fairly common at Christmas for most years of the war, with football matches in particular becoming a feature for those stationed behind the lines.

Events like this helped to show the common similarities between Entente soldiers but they could also highlight the differences. In 1914, the British soldiers each received a present from Princess Mary in the form of a golden tin. These tins contained tobacco and cigarettes as well as a pipe, lighter, pencil and paper for writing home, chocolates, spices, and a picture of Princess Mary alongside a Christmas Card. These tins were produced and supplied following a fundraising drive by Princess Mary to ensure that ‘every sailor afloat and every soldier at the front’ would receive something on Christmas Day. However, upon seeing these gifts, French and Belgian soldiers were given a clear indication of the apparent disparity in wealth between them and the British (and Britain in general) that would allow each British soldier to receive a gift of this nature.

Whilst the attempts to maintain combat focus along the front would mean that significant numbers of soldiers would remain in the front lines over Christmas, those stationed behind the lines could enter a strange world of both civilian and military life. It was not uncommon for British soldiers to spend Christmas day at the homes of French or Belgian civilians that they had befriended over the preceding months. Additionally, gatherings of allied soldiers in local bars and cafes were also widespread and these would often result in hearty singing between the various nationalities.

Whilst the war did not really stop over Christmas, and the battles of Verdun and the Somme had largely put paid to any real attempts to form truces between opposing men by 1916, it did change noticeably for the combatants. All were aware that they were far from home on what was traditionally a day spent with family. The moves to celebrate with local families was largely motivated by an attempt to fill this gap with some form of recognisable structure and festive friendliness.

Following on from their disaster at the Battle of the Boar’s Head, the 11th, 12th, and 13th ‘Southdowns’ Battalions of the Royal Sussex Regiment spent a restful Christmas in 1916 with the official war diary for the 13th Battalion stating that; ‘Every effort was made to provide a suitable dinner for the men on Christmas Day and the Christmas Meal was apparently a great success.‘ Christmas Day 1917 saw the men of the three battalions given the option of attending church services and parades.

For those left at home, they were also reminded and encouraged to send Christmas to the front in some way, shape or form so as to ensure to their loved ones that they (and their country) had not forgotten them.

- Untitled WW1 Christmas Card – © IWM (Art.IWM PST 13397)

- Buy a Christmas Present – © IWM (Art.IWM PST 10797)

- Mikulás Idén a Rokkant Katonáké [This Year Santa Claus Belongs to the Invalid Soldiers] – © IWM (Art.IWM PST 7182)

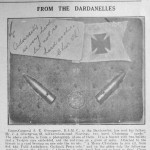

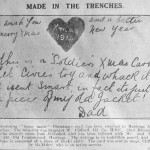

Some soldiers who didn’t have access to everyday Christmas cards improvised in a variety of inventive ways. One man adapted a hard biscuit into a card, complete with embedded bullets, and sent it back to his family in Hastings from Gallipoli. Sergeant W. Clifford, whilst stationed in Hastings, received a card from his father who was on active duty in France. This card was adapted out of a piece of the soldier’s khaki jacket. Another Christmas card arrived made out of a shell fragment.

- From the Dardanelles 23 December 1915 – Hastings and St Leonards Pictorial Advertiser

- Merry Xmas Card 7.01.15 – Hastings and St Leonards Pictorial Advertiser

- Xmas Card made of Shell – 24 December 2014 – Hastings and St Leonards Pictorial Advertiser

- Xmas Card 1916 – Hastings and St Leonards Pictorial Advertiser

Christmas on the Home Front

Christmas on the East Sussex Front in 1914 and 1915 was marked by particularly severe weather with a ‘hurricane’ being reported in 1914 and bad flooding in Alexandra Park, Hastings in 1915.

- In the wake of a Hurricane – 31 December 1914

- Flood in the Alexandra Park – 16 December 1915

The continuation of the war, combined with the presence of wounded or undeployed soldiers around East Sussex, meant that the festive period was often tinged with a mix of sadness for those away at the front, or who had lost their lives, and acknowledgement of the soldiers who were currently in Britain.

The Hastings and St Leonards Pictorial Advertiser reported on several Christmas events being held for convalescent soldiers in East Sussex hospitals.

- Christmas Cheer for Convalescent Soldiers – 30 December 1915

- Tommy’s Christmas at West Dene Hospital – 30 December 1915

Some soldiers recovering at the Filsham Park Hospital during the war made the most of sudden snowy conditions whilst also decorating a tree.

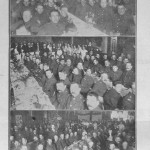

Other stories about soldiers undergoing exercises, undertaking Christmas Church Marches, or being given large Christmas dinners also appeared in newspapers during the war.

- With the Troops at Christmas – 28 December 1916 – Hastings and St Leonard Pictorial Advertiser

- Staffordshires’ Church Parade on Christmas Day – 31 December 1914 – Hastings and St Leonard Pictorial Advertiser

- Christmas Dinner Snapshots – 30 December 1916 – Hastings and St Leonard Pictorial Advertiser

Christmas in East Sussex was also marked by the arrival of presents from America for the children of British soldiers. However, the gifts that arrived in Hastings turned out to be a disappointment to those who received them. Only two toys had been sent and both were reported to be broken. There were a few American games and some food but an overwhelming number of gloves, hats, and pairs of underwear, most of which originated from Texas, appeared to be the Christmas bounty for Hastings. There may have been disappointment at the gifts received from America but toy makers in East Sussex were busy ensuring that their hard work would be met with excitement.

- Presents from the States – 24 December 1914 – Hastings and St Leonard Pictorial Advertiser

- Gifts from US to Children of British Soldiers – disappointment (24 Dec 1914) – Hastings and St Leonard Pictorial Advertiser

- Toy Makers – 17 December 1914 – Hastings and St Leonard Pictorial Advertiser

Whilst some people did believe that the war would be over by Christmas 1914, this belief is not as widespread as we think. In all, many soldiers ended up spending four years of war in the trenches over Christmas time and the majority still had not been released from service, or “demobbed,” by Christmas 1918. As they coped with this distance away in Europe and else where, their families had to learn to deal with it back home.

Many came to understand that if they could not reunite for Christmas itself then there were ways they could attempt to replicate the experience and the spirit whilst the war continued.

Sources

Hastings and St Leonard Pictorial Advertiser

Imperial War Museum Archives

West Sussex Record Office